Abiotic Factors in Biology: The Invisible Architects Shaping Life on Earth

Abiotic Factors in Biology: The Invisible Architects Shaping Life on Earth

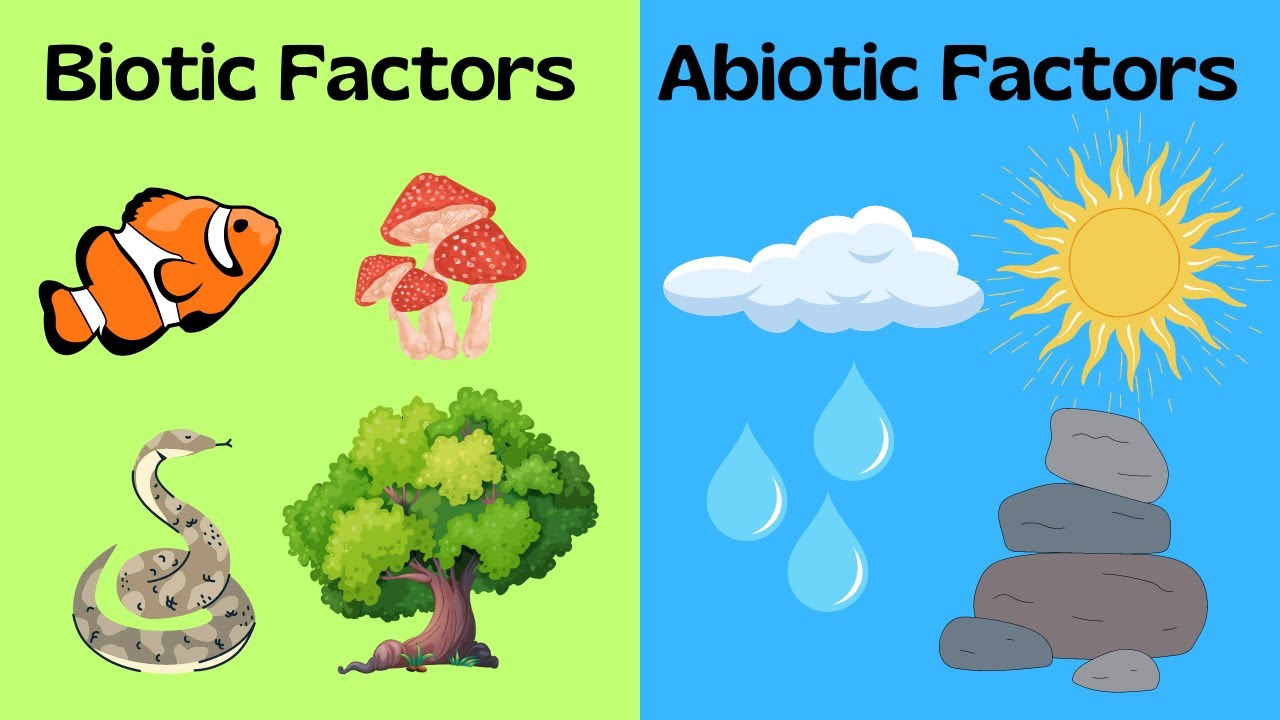

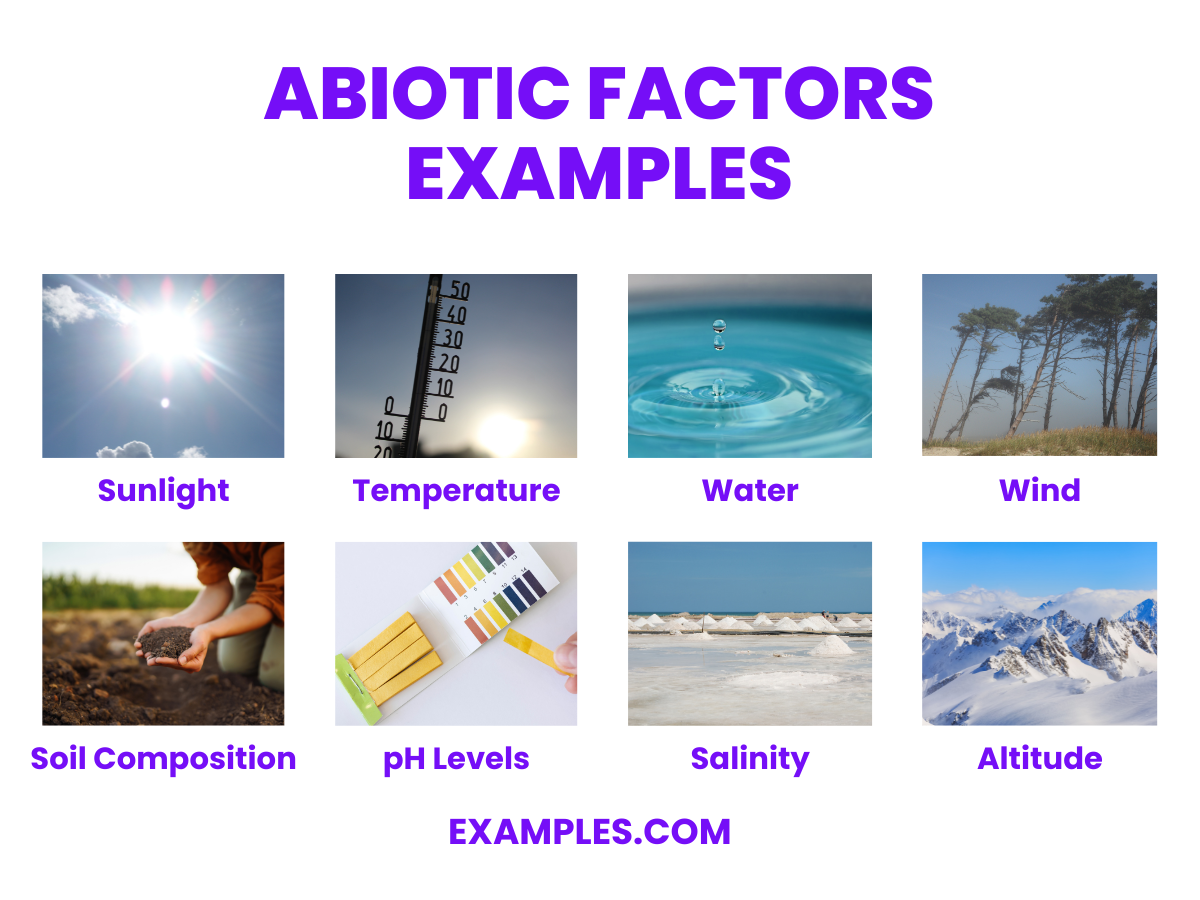

In the intricate web of life, where every organism interacts with its surroundings, abiotic factors stand as the silent but powerful forces governing survival, distribution, and evolution. Defined in biological terms as non-living environmental components—such as temperature, light, water, air, soil composition, and substrate texture—abiotic factors create the foundational conditions that determine which species thrive in a given habitat. These elements do not sustain life directly through metabolism, yet their influence is everywhere: from deep ocean trenches to sun-baked deserts, every ecosystem responds critically to shifts in these physical and chemical parameters.

Understanding abiotic factors is essential for deciphering ecological dynamics, predicting species adaptation, and addressing global challenges like climate change.

The Core Definition: What Are Abiotic Factors?

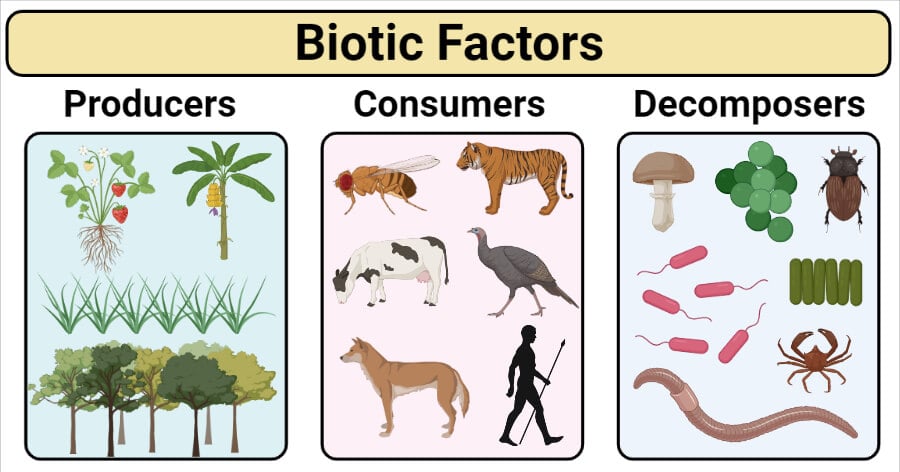

Biologically, abiotic factors encompass all non-organic components of an environment that impact living organisms. Unlike biotic elements—such as plants, animals, and microbes—that participate directly in biological processes through consumption, reproduction, or symbiosis, abiotic factors act as environmental determinants. These include measurable physical and chemical properties: temperature and thermal gradients, light intensity and photoperiod, soil pH and nutrient availability, water salinity and flow, atmospheric gases, wind patterns, and mineral composition.

Each factor operates within specific ranges—known as tolerance windows—beyond which organisms face physiological stress or mortality. The interaction of these elements forms complex gradients across landscapes, driving gradients in biodiversity and ecosystem structure. “Abiotic conditions are often the primary filters that determine where species can live,” explains ecologist Dr.

Elena Marquez, “they define the niche boundaries, shaping survival strategies across evolutionary timescales.”

Temperature: The Universal Life Regulator

Temperature is one of the most influential abiotic factors, governing metabolic rates, enzyme activity, and reproductive cycles. Organisms exhibit distinct thermal optima—ideal temperature ranges for growth and function—regulated by evolutionary adaptation. For instance, tropical rainforest species, adapted to stable warm climates, may perish when exposed to sudden cold snaps, while tundra plants endure extreme frigidity with specialized antifreeze proteins.

Temperature fluctuations also drive seasonal behaviors: migration, hibernation, and flowering cycles. In aquatic systems, thermal stratification creates distinct zones—epilimnion, metalimnion, hypolimnion—each supporting different microbial and fish communities. Global warming is shifting these thermal envelopes rapidly, forcing species to migrate poleward or risk local extinction.

“Temperature isn’t just a background condition—it’s an active architect of biodiversity,” notes climatobiologist Dr. Aris Thorne.

Light: Energy Source and Ecological Signal

Sunlight fuels nearly all life on Earth primarily through photosynthesis, making light intensity, duration, and quality critical abiotic components. In terrestrial ecosystems, light drives plant productivity, shaping canopy structure and understory diversity.

Shade-tolerant species thrive in low-light conditions, while sun-adapted plants optimize leaf orientation and surface area to capture maximum irradiance. Beyond energy, light influences circadian rhythms and photoperiodism—response to day length—that regulate flowering, breeding, and migration. Aquatic ecosystems depend especially on light penetration, with depth zones defined by light availability: the photic zone supports photosynthetic organisms, while the aphotic zone harbors extremophiles adapted to perpetual darkness.

Artificial light pollution is increasingly altering these natural cycles, disrupting pollination patterns and predator-prey dynamics. As ecologist Dr. Lila Chen observes, “Light is not just energy—it’s a season’s clock, a signal, and a survival cue.”

Water and Humidity: The Essence of Life’s Balance

Water, both as a physical substance and hydration source, ranks among the most vital abiotic factors.

Its presence dictates species distribution, physiological adaptation, and ecosystem form. Aquatic habitats—from freshwater lakes to hypersaline lagoons—support unique communities based on water chemistry and flow. On land, water availability shapes plant form: succulents in arid zones store moisture, while deep-rooted trees access underground reserves.

Soil moisture and humidity interact to regulate transpiration rates, nutrient uptake, and microbial activity. Desert biomes exemplify extreme water limitation, where organisms evolve from water-conserving physiological traits to behavioral avoidance of peak heat. In contrast, wetlands thrive due to consistent saturation, fostering biodiversity hotspots.

Climate shifts reducing precipitation or increasing evaporation intensify water stress, threatening freshwater species and altering biome boundaries. As hydrologists warn, “Water’s rhythm—distribution, purity, and timing—underpins ecosystem resilience.”

Soil Composition and Substrate: Foundation and Habitat

Soil is far more than inert dirt; it is a dynamic abiotic matrix composed of minerals, organic matter, water, and air. Its texture—sand, silt, clay—and structure—aggregation—control drainage, aeration, and nutrient retention.

pH and cation exchange capacity govern chemical availability, affecting plant nutrient uptake and microbial metabolism. In terrestrial ecosystems, soil fertility directly influences primary productivity, with nutrient-poor substrates like itchite in tropical rainforests fostering specialized mycorrhizal partnerships. Substrate type further defines habitat suitability: rocky outcrops favor cushion plants with narrow root systems, while loose sediments support burrowing invertebrates.

Soil biota, though biotic, interact closely with abiotic soil chemistry, creating feedback loops that sustain or degrade ecosystem health. Degraded soils, stripped of organic content and structure, collapse ecological function—an omen of unsustainable land use. “Soil is the living skin of the Earth,” says pedologist Dr.

Rajiv Mehta, “and its abiotic properties are nonnegotiable for ecosystem integrity.”

Air Composition and Atmospheric Forces: Breathing Space and Climate Drivers

Atmospheric conditions—oxygen levels, carbon dioxide concentration, humidity, and air pressure—shape how organisms function and disperse. Oxygen, vital for aerobic respiration, varies with altitude, temperature, and photosynthetic activity; high-elevation species often exhibit enhanced oxygen-binding capacities. Carbon dioxide, although a trace gas, drives photosynthesis and influences climate through greenhouse effects.

Air pressure and humidity regulate water loss via transpiration and evaporation, impacting species distribution, especially in extreme environments like alpine zones or deserts. Wind patterns disperse seeds, spores, and pollinators, facilitating gene flow and colonization. Human activities—combustion, deforestation, industrial emissions—are rapidly altering atmospheric composition, pushing ecosystems beyond historical abiotic norms.

“The atmosphere is a shared envelope of life,” notes atmospheric biologist Dr. Sofia Alvarado, “and our reshaping of its chemistry reverberates through every trophic level.”

Pore Space and Debris: The Hidden Microhabitat Puzzle

Beyond macro-level factors, abiotic micro-environments play pivotal roles. Pore space within soil and leaf litter governs water retention, root penetration, and microbial niches.

Detrital debris—fallen leaves, dead wood, fecal matter—creates organic substrates supporting decomposer communities critical to nutrient cycling. These fragmented materials buffer temperature extremes, retain moisture, and filter toxins, enhancing habitat complexity. In reef ecosystems, coral skeletons and algae skeletons form intricate pore networks that harbor mobile and stationary organisms alike.

Even mineral flakes and ash influence chemical gradients, accelerating weathering and nutrient release. “The abiotic matrix is a mosaic of microhabitats,” emphasizes ecologist Dr. Nia Okoro, “each pore, fragment, and particle a sanctuary or a challenge for life.”

Abiotic factors operate not in isolation but in dynamic interplay, forming environmental gradients that define ecological limits.

A mountaintop, for example, presents a steep cline: reduced oxygen and temperature at higher elevations select for cold-tolerant, low-growing species, while lower slopes support diverse, warm-adapted communities. Such gradients drive zonation—distinct ecological bands—and foster biodiversity through specialization. Climate change accelerates shifts in these gradients, compressing suitable habitats and increasing extinction risks for species with narrow tolerances.

Understanding abiotic drivers thus enables predictive modeling of ecosystem responses, vital for conservation, agriculture, and climate adaptation strategies.

From the microscopic pore in soil to the global atmosphere, abiotic factors are the silent scaffolding upon which life is built. They set boundaries, create opportunities, and enforce constraints—shaping evolution, distribution, and ecosystem function with relentless precision. As human influence intensifies environmental change, the study of abiotic conditions grows ever more urgent.

By decoding these non-living forces, biologists and ecologists gain not just insight—but a roadmap for preserving Earth’s intricate web of life. Abiotic factors are not background noise; they are the fundamental stage upon which biology performs its stage of existence.

Related Post

Town Mineral Water’s Hidden Secret: Fighting Sluggishness — Dr. Heather Heck Bounds What Matters in Every Sip

India’s Global Icons: The Top 10 Most Popular Actors Redefining Film Stardom Worldwide

M: Information Systems Read Online

From Vast Estimates to Pinpoint Accuracy: The Critical Transformation in Time Management at 7:30 PM EST