Chemical Geometry: The Silent Architect of Molecular Shape and Function

Chemical Geometry: The Silent Architect of Molecular Shape and Function

Understanding how molecules fold, bond, and interact hinges on a foundational concept in chemistry: chemical geometry. Far more than a static arrangement of atoms, molecular geometry dictates reactivity, polarity, stability, and even biological performance—all emerging from the precise spatial organization of electrons and nuclei. With roots deeply embedded in quantum mechanics and VSEPR theory, chemical geometry reveals the invisible blueprint shaping everything from enzyme catalysis to drug design.

As scientists continue to probe molecular landscapes with increasing precision, the nuances of chemical geometry prove indispensable in unlocking functional insights across fields from materials science to pharmaceutical development. The heart of chemical geometry lies in predicting and interpreting molecular shapes based on electron pair repulsion—a principle crystallized in the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory, first formalized by Sidgwick and Powell in the mid-20th century and later refined by Gillespie and Nyholm. This model posits that electron domains—whether bonding pairs or lone pairs—arrange themselves spatially to minimize repulsive forces, thereby defining the molecule’s three-dimensional form.

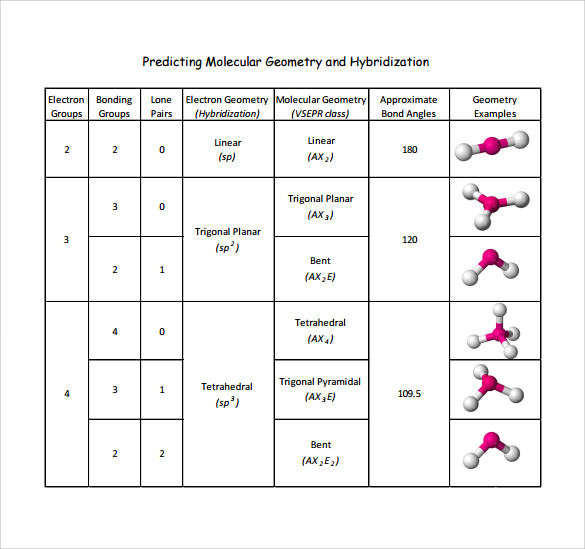

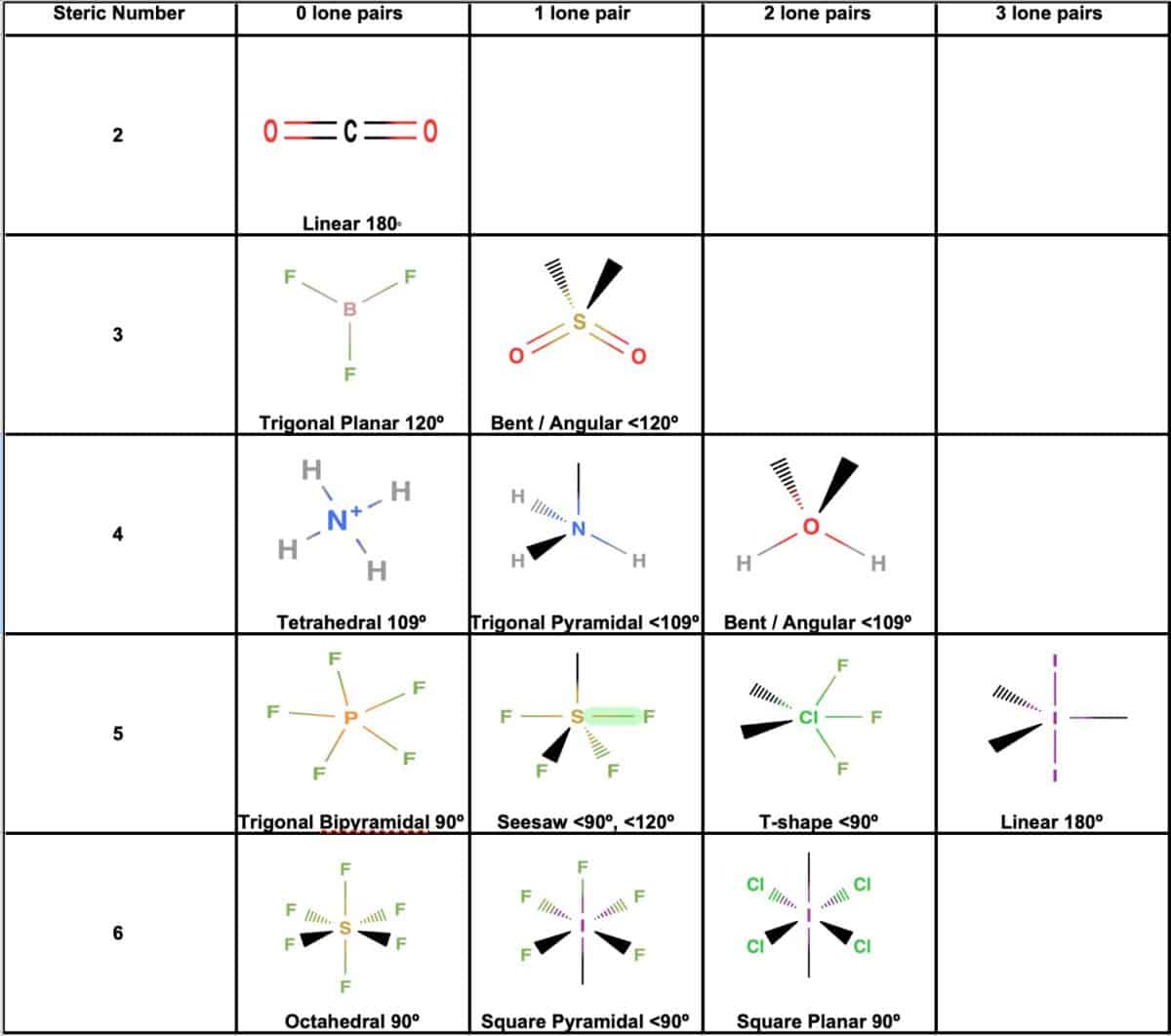

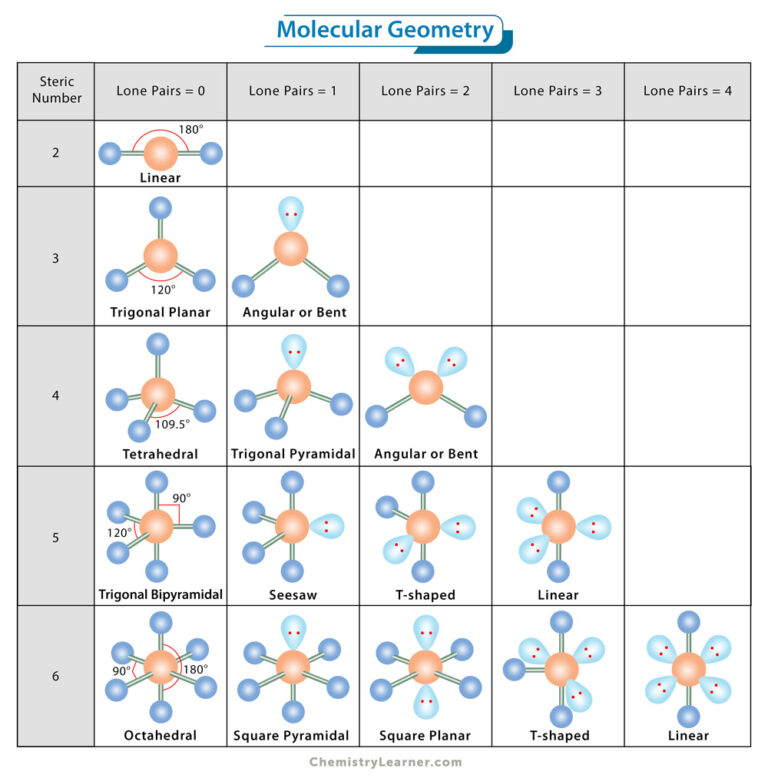

For instance, ammonia (NH₃), with its lone pair on nitrogen, adopts a trigonal pyramidal geometry, a result of sp³ hybridization and optimized repulsion among electron clouds. In contrast, carbon dioxide (CO₂), with two double bonds and no lone pairs, assumes a linear structure, the simplest outcome of sp hybridization. How Electron Pair Repulsion Dictates Form VSEPR theory provides a ranked hierarchy of repulsive energies: lone pair-lone pair > lone pair-bond pair > bond pair-bond pair.

This ranking explains why molecular shapes deviate from ideal symmetry. Water (H₂O), for example, exhibits a bent structure at 104.5°—narrower than the tetrahedral angle of 109.5°—due to significant lone pair repulsion compressing the H–O–H bond angle. Such deviations are not mere curiosities; they reflect deeper energetic balances that govern molecular behavior.

Transitioning beyond idealized models, modern chemical geometry incorporates molecular orbital theory and hybridization concepts to explain bonding patterns and electron delocalization. Hybridization—such as sp² in boron trifluoride (BF₃) or sp³d in phosphorus pentachloride (PCl₅)—informs the directional nature of bonds and helps predict molecular geometry with greater accuracy. In BF₃, the central boron atom utilizes unhybridized p orbitals to participate in π bonding with fluorine’s lone pairs, forming a planar structure optimal for electron sharing.

This orbital-based explanation bridges classical VSEPR with quantum mechanical precision, revealing that geometry arises from the marriage of atomic orbitals and electron density distribution. The predictive power of chemical geometry extends far beyond textbook examples. In coordination chemistry, ligand field theory builds on geometric principles to determine the spatial arrangement of d-orbitals around transition metal centers—critical for understanding catalytic activity and electronic transitions.

Octahedral, square planar, and tetrahedral configurations are not arbitrary; they stem directly from symmetry minimization and orbital overlap considerations. In organic chemistry, stereochemistry—closely tied to geometry—controls reactivity and product selectivity. The D–L convolution of chiral centers in asymmetric synthesis relies on precise three-dimensional control, enabling everything from rainbows of pharmaceutical enantiomers to high-performance polymers.

Step beyond single molecules and examine chemical geometry’s role in materials science. Crystallography, which depends on long-range atomic coordination ideals, relies on geometric packing principles—close-packed arrangements like FCC or HCP—to engineer metals, semiconductors, and ceramics with tailored mechanical and thermal properties. Advances in X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy now allow direct visualization of atomic positions, validating theoretical predictions and revealing subtle distortions caused by strain, doping, or phase transitions.

Such insights fuel breakthroughs in superconductors, catalysts, and battery materials, where atomic spacing and bond angles directly influence functionality. Even in nanoscale systems, chemical geometry governs shape and reactivity. Gold nanoparticles exhibit geometrically distinct facets—cubic, octahedral, or truncated pyramidal—each exposing unique coordination environments that alter catalytic efficiency.

Similarly, in DNA’s double helix, the precise antiparallel geometry of deoxyribose-phosphate backbones, maintained by hydrogen-bonding geometry, ensures structural stability and accurate replication. These examples underscore a pivotal truth: the spatial arrangement of atoms and electron pairs is not passive but dynamic, responsive, and determinative. The journey from theoretical models to real-world application reveals chemical geometry as both a foundational science and a practical toolkit.

Its principles, though seemingly abstract, underpin innovations in drug discovery, where pharmacophores must fit biological targets with atomic precision. Designing kinase inhibitors or protease blockers relies on geometric complementarity to ensure binding affinity and selectivity. In environmental chemistry, understanding the geometry of pollutant molecules—such as the tetrahedral structure of perchloroethylene—guides remediation strategies and risk assessment.

Quantum mechanical simulations now push the boundaries of classical geometric models, computing electron density maps and predicting distortions from thermal motion, solvent effects, and external fields. Yet, despite these computational advances, the core principles—VSEPR repulsions, hybridization, and orbital symmetry—remain unchanging. They serve as a Rosetta Stone, translating the language of electrons into the grammar of molecules.

In sum, chemical geometry is not a peripheral subdiscipline but a central pillar of modern chemistry. It deciphers the choreography of atoms in space and time, revealing why molecules assume the shapes they do—and why those shapes matter. From embryonic development shaped by chiral biomolecules to the quantum-coherent geometries of catalysts, this discipline continues to illuminate the molecular underpinnings of matter and life.

Its enduring relevance is undeniable, as every new discovery confirms that chemistry is, at its core, the science of geometry.

Understanding chemical geometry demands a synthesis of theory, experiment, and intuition—a multidisciplinary vigilance that ensures that the invisible becomes not just visible, but meaningful. As analytical tools grow more sophisticated, the precision of geometric predictions deepens, reinforcing chemistry’s role as the architect of molecular function in science and society.

Related Post

What Time Is It in British Columbia Right Now? Stay Precise, Stay Synchronized

Ronda Rousey’s Allure: How Sexy Photos Captivated Fans and Redefined Her Public Image

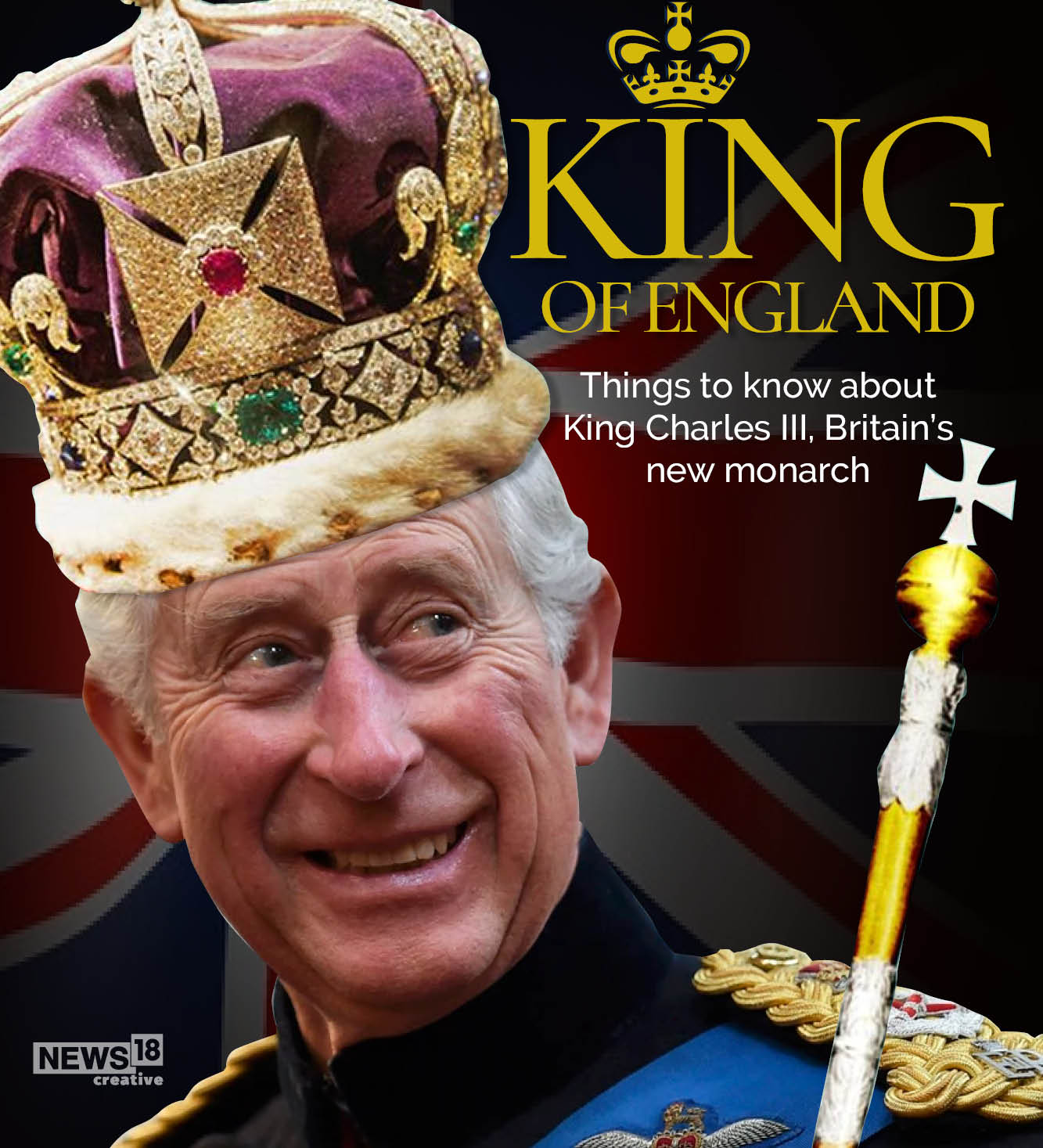

King Charles 111 Emerges as a Steadfast Monarch in Britain’s Modern Age

Starbucks SummerGame: How the Iconic Chain Transformed Ordered Coffee Into a Mobile Festival Experience