Decoding the Atom: A Daily Dive into the Science Behind Nuclear Reactor Theory

Decoding the Atom: A Daily Dive into the Science Behind Nuclear Reactor Theory

Nuclear reactor theory underpins one of humanity’s most debated yet potent energy technologies, merging complex physics with real-world safety and efficiency. This guide explores the foundational principles, operational mechanics, and strategic evolution of nuclear reactors, revealing how controlled chain reactions power modern grids while managing inherent risks. From thermal fission to fast breeders and fusion’s long-term promise, understanding reactor theory is key to navigating today’s energy landscape, shaping policies, and advancing safe, sustainable power solutions.

At its core, nuclear reactor theory is a sophisticated interplay of neutron kinetics, materials science, and thermodynamics—concepts that transform atomic-scale processes into continent-scale electricity generation.

The Core Mechanism: How Nuclear Fission Powers Reactor Systems

At the heart of every nuclear reactor lies a controlled chain reaction—a self-sustaining process where neutrons initiate fission, releasing energy and new neutrons to continue the cycle. Fission occurs when a neutron collides with a fissile nucleus, most commonly uranium-235 or plutonium-239, causing the nucleus to split and emit multiple neutrons.These secondary neutrons trigger adjacent nuclei, creating a cascade if carefully regulated. This process is sustained through a balance of neutron multiplication and cancellation—measured by the multiplication factor, k. When k equals 1, a steady reaction persists; values above 1 risk runaway power, while below 1 terminate the reaction.

“Precision in neutron economy defines reactor stability,” notes nuclear physicist Dr. Elena Marquez. Operations rely on fuel assemblies—packages of enriched uranium or plutonium oxide—surrounded by moderators like light water or graphite that slow neutrons to thermal energies, increasing fission probability.

Control rods, composed of neutron-absorbing materials such as cadmium or boron, fine-tune reactivity by adjusting neutron availability. Understanding neutron behavior is essential: too few neutrons stall the reaction; too many generate excessive heat. This delicate equilibrium demands advanced modeling and real-time instrumentation, forming the bedrock of reactor control and safety.

Reactor Types: Thermal, Fast, and the Evolution of Fuel Cycles

Nuclear reactors are categorized by neutron energy and cooling method, each optimized for specific fuel uses and power outputs. Thermal reactors dominate the landscape, operating at low neutron energies using moderators to thermalize neutrons. Light-water reactors (LWRs), including pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs), are the most widespread, accounting for over 60% of global nuclear capacity.Their reliance on enriched uranium balances cost and performance, making them suitable for baseload electricity. In contrast, fast reactors operate with high-energy neutrons, enabling fuel reuse through breeding—converting non-fissile uranium-238 into plutonium-239. This process supports closed fuel cycles, reducing long-lived radioactive waste and conserving uranium resources, though complexity and cost limit widespread deployment.

France’s RECP (Rapid Critical Test Reactor) and Russia’s BN-800 exemplify advances in fast neutron technology, aiming to close the fuel loop sustainably. Hybrid designs merge features—such as high-temperature gas-cooled reactors (HTGRs) using helium coolant and graphite moderators—which operate at higher temperatures for efficient electricity and industrial heat, boosting exergy efficiency compared to traditional steam cycles. Each reactor type reflects a trade-off between proliferation risk, sustainability, and technological maturity.

Selecting the optimal design requires balancing these factors against energy goals, waste policies, and safety requirements.

Safety, Waste, and the Human Element in Reactor Operations

Safety in nuclear reactors is a multi-layered discipline, built on defense-in-depth strategies that integrate physical barriers, engineered systems, and rigorous procedural protocols. Core containment structures—massive steel and concrete shells—protect against internal pressure and radioactive release, while passive safety features, such as natural convection cooling, reduce reliance on active systems during emergencies.Historical incidents like Chernobyl and Fukushima underscored gaps in operator training, emergency response, and natural hazard planning. Post-accident reforms introduced improved containment designs, enhanced emergency control systems, and mandatory probabilistic risk assessments. Today, modern reactors employ inherently safer concepts—such as low-pressure Operation and Passive Safety Systems (LOPESS) in advanced LWRs—to minimize human and environmental risk.

Nuclear waste management remains a pivotal challenge. High-level waste, primarily spent fuel, demands isolation over millennia, prompting research into deep geological repositories like Finland’s Onkalo facility. Interim storage solutions, including dry cask systems, buy time for long-term strategies.

“Waste is not a dead end—it’s a resource in a closed cycle,” argues Dr. James Holloway, a senior advisor on sustainable fuel chain development. Beyond technical safeguards, cultural resilience defines operational excellence.

Training, transparency, and continuous improvement foster a safety-first ethos, essential for maintaining public trust in nuclear energy’s role within a low-carbon future.

The Future: Advanced Designs and the Path to Sustainable Power

The evolution of nuclear reactor theory now pushes beyond conventional uranium-fueled thermal reactors toward next-generation systems designed for efficiency, safety, and environmental harmony. Generation IV reactors—such as molten salt reactors (MSRs), sodium-cooled fast reactors (SFRs), and fully lead-cooled designs—offer transformative benefits: reduced waste, enhanced proliferation resistance, and compatibility with diverse fuel cycles.MSRs, for instance, dissolve fuel in liquid salt, enabling continuous processing and higher thermal efficiency while inherently limiting meltdown risks. Small modular reactors (SMRs), compact and factory-built, promise lower capital costs and scalable deployment for remote or decentralized grids, accelerating nuclear’s role in regional energy resilience. Beyond fission, fusion remains the ultimate aspiration—a clean, potentially limitless energy source.

Projects like ITER and Commonwealth Fusion Systems’ ARC reactor target breakthroughs in plasma confinement and net energy gain. While still in experimental phases, fusion’s success would redefine reactor theory, unlocking a future where energy is virtually limitless and environmentally benign. As climate urgency intensifies, nuclear reactor theory stands at a crossroads—balancing proven reliability with audacious innovation.

The challenge lies not only in engineering mastery but in building public confidence, policy coherence, and global cooperation to harness the atom’s power responsibly for generations to come.

Related Post

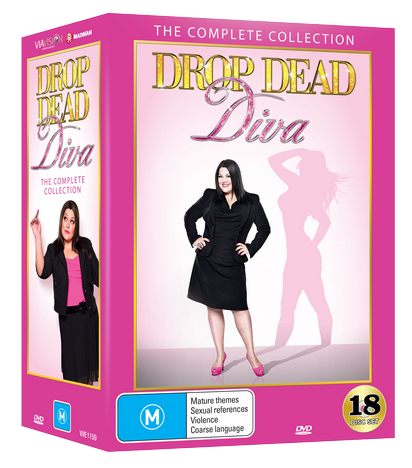

Where Can I Stream Drop Dead Diva? The Complete Guide to Watching the Crime Comedy on Demand

Maggie Laughlin’s Enigmatic Life: Married to Clarke Finney, Ties to Romo and San Antonio, Sparking Hot Reporting

New KRLN Executor V663: Your Ultimate Guide to Streamlining Workflow and Maximizing Efficiency

Unlock Free Skos Samples on Walmart and Sams Club: A Rare Retail Acquisition Opportunity