Defining the Consumer: A Scientific Lens on Decision-Making in Modern Economies

Defining the Consumer: A Scientific Lens on Decision-Making in Modern Economies

At its core, a consumer is defined in economic terms as an individual or group that acquires goods and services for personal use or consumption rather than for resale or business purposes. This precise scientific definition underscores a critical distinction: consumers are end-users whose choices drive market demand and shape economic activity. Unlike businesses that operate with profit maximization as their primary goal, consumers act based on subjective preferences, perceived value, and resource constraints.

The consumer’s role transcends passive receipt—they are active agents in a complex system where behavior influences supply chains, pricing, and innovation. Understanding consumers through a scientific framework reveals deeper layers of decision-making logic. Economists employ models that treat consumers as rational actors seeking utility maximization within budget limits.

This rational choice theory, pioneered by economists such as Paul Samuelson, posits that individuals evaluate trade-offs—weighing price, quality, convenience, and personal benefit—before selecting options. Yet behavior is rarely strictly rational; cognitive biases, emotional drivers, and social influences introduce nuanced variation. Behavioral economics, a distinct scientific discipline, integrates psychology to explain deviations from “perfect rationality,” showing consumers are simultaneously logical calculators and emotionally guided decision-makers.

Central to the scientific definition of the consumer is their function as an economic driver. Every purchase represents a signal: it communicates preferences, reflects income capacity, and influences production trends. When large populations consistently favor organic foods, electric vehicles, or streaming subscriptions, markets respond with innovation and adaptation.

This dynamic feedback loop illustrates how consumer behavior is both shaped by and shapes societal transformation. - Consumers are rational yet behaviorally influenced decision-makers. - They respond to price signals, income levels, and psychological cues.

- Demand patterns emerge from individual choices, collectively fueling market change. From a statistical perspective, consumers are defined by observable patterns: frequency of purchases, brand loyalty, sensitivity to discounts, and value perception. Researchers employ survey data, transaction records, and experimental methods to map these behaviors.

Segmentation models categorize consumers based on demographics, psychographics, and buying habits—enabling businesses and policymakers to anticipate needs and forecast trends. For example, a “value-conscious consumer” may prioritize affordability over premium features, while an “experience seeker” might pay higher prices for personalized or exclusive offerings. Market analytics tools transform personal choices into predictive insights, guiding everything from inventory management to public policy. The scientific consumer thus emerges not just as a data point, but as a cornerstone of economic analysis.

A global study by the OECD reveals that younger consumers in urban centers often prioritize sustainability and digital integration, whereas older or rural populations may emphasize cost-effectiveness and reliability. This heterogeneity challenges broad generalizations; the scientific definition must accommodate the richness of human behavior. The role of cognitive and emotional drivers in consumption further complicates the picture.

Neuroscientific research shows that decision-making activates brain regions linked to emotion, memory, and reward, not just calculation. The brain’s response to branding, packaging, or promotional messaging can initiate purchase behavior independently of explicit logic. Marketers and economists now integrate these findings to refine predictive models, blending neuroscience with traditional econometrics.

Quantifying consumer heterogeneity remains a sophisticated challenge. Traditional metrics like average spending per capita fail to capture nuanced segmentation. Advanced clustering algorithms, applied to big data from mobile payments, social media, and loyalty programs, now allow for dynamic profiling.

These techniques identify micro-segments—such as “impulse buyers” triggered by digital ads or “delay-sensitive shoppers” responsive to limited-time offers—enabling personalized engagement strategies grounded in empirical evidence. Consumer Behavior as a Feedback Loop in Market Evolution The interaction between consumers and markets forms a continuous feedback loop, foundational to economic theory. Consumer demand drives product development, pricing strategies, and distribution channels, which in turn reshape expectations and habits.

For example, the rise of e-commerce was catalyzed first by changing consumer preferences for convenience and choice, later amplified by platform innovations like one-click ordering and algorithm-driven recommendations. “The consumer is not a static entity but a dynamic force—constantly adapting, learning, and redefining economic boundaries,”* —Dr. Elena Marques, Behavioral Economist This adaptability underscores the consumer’s role as both subject and agent.

Shifts in perception—fueled by information, trends, or societal values—can rapidly transform markets. Consider the surge in plant-based diets, driven by environmental awareness and health consciousness. This demand prompted food industries to innovate, resulting in alternative proteins, sustainable packaging, and eco-certifications—all measurable outcomes of consumer influence.

Statistical studies further illuminate this cycle. Time-series analyses track how changes in consumer confidence indices correlate with spending rates, GDP growth, and employment trends. Panel data from household surveys reveal how demographic shifts—such as aging populations or urbanization—affect consumption patterns across countries.

These insights empower governments and corporations to anticipate needs, allocate resources efficiently, and design responsive policies. Yet, challenges persist. Information asymmetry, cognitive overload, and behavioral manipulation through targeted advertising complicate the idealized economic model.

Ethical considerations demand transparency and safeguards to protect consumer autonomy. Regulatory frameworks increasingly recognize consumers as rights-bearing agents, not merely transactional units. The scientific definition of the consumer, therefore, extends beyond transactional behavior to encompass sociocultural context, psychological depth, and systemic influence.

In a world where data shapes nearly every aspect of life, understanding consumers with rigor and nuance is not just an academic pursuit—it is essential for innovation, equity, and sustainable growth. The consumer stands at the crossroads of markets and human values, and their behavior remains one of economics’ most compelling, complex frontiers.

Related Post

Top Minecraft MMORPG Servers: No Premium Needed – Fully Functional Elite Multiplayer Without the Paywall

Angela Giarratana Dating: Unveiling the Personal Side of a Rising Hollywood Star

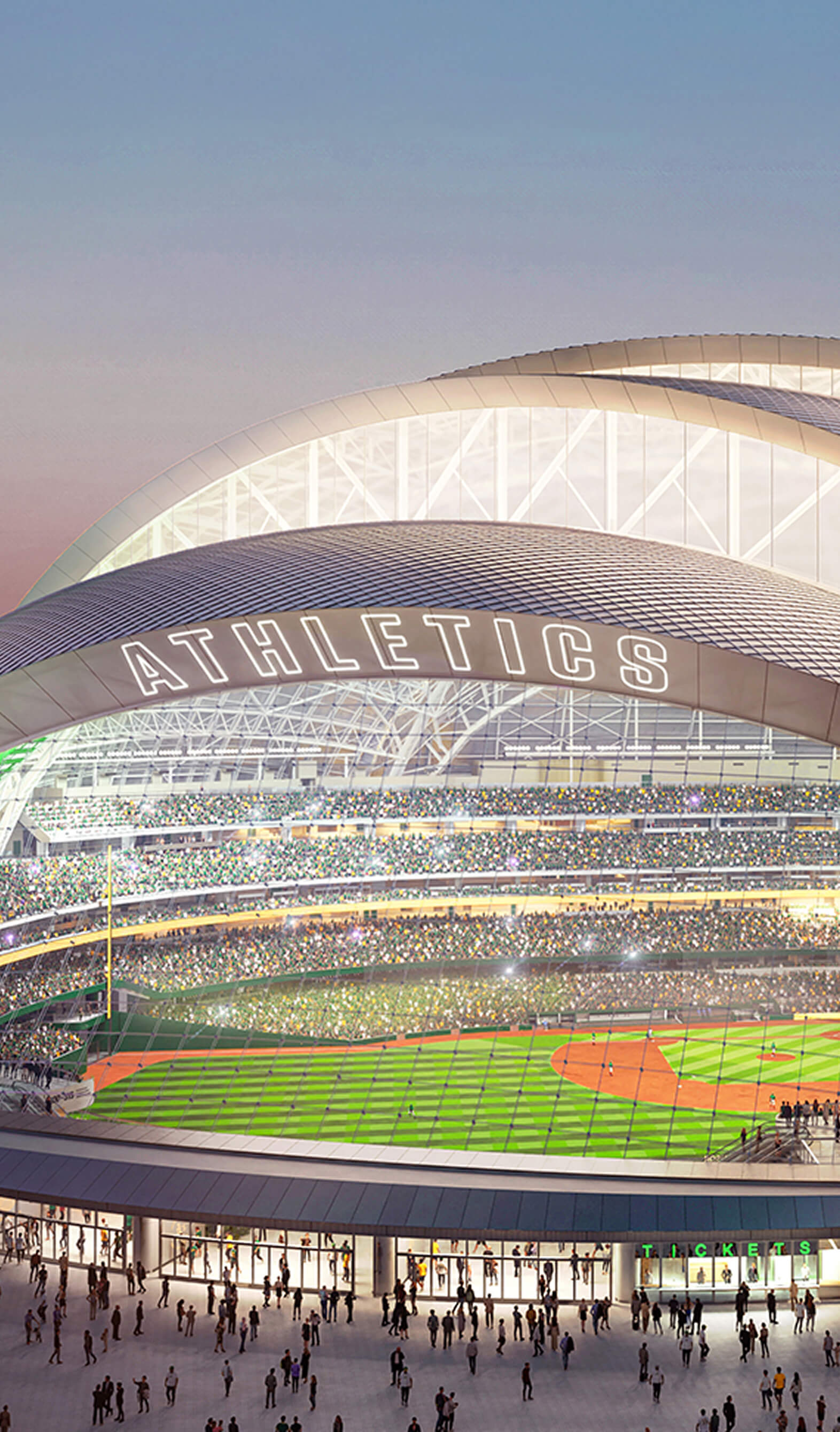

Red Oaks Show: The Quiet Powerhouse Reshaping Va’s Most Flamboyant Ballpark Experience

How Many Bridges Cross Portland’s Rivers? A Deep Dive into the City’s Spanning Legacy