Does California Tax Social Security? Unmasking the Hidden Tax on Retirement Income

Does California Tax Social Security? Unmasking the Hidden Tax on Retirement Income

Residents of California face a complex financial reality when it comes to Social Security benefits—many mistakenly believe these federally administered earnings are fully exempt from state taxation, but in truth, Social Security income can be subject to state income tax, with California’s rules adding further nuance. While federal law generally exempts up to 85% or 50% of Social Security benefits depending on income thresholds, California’s tax treatment introduces an important layer that affects thousands of retirees annually. Understanding how the Golden State taxes this federal benefit is crucial for maximizing net retirement income.

California does tax Social Security benefits, but not uniformly. The state applies its own tax code to determine whether any portion of a retiree’s federal Social Security income is subject to state taxation, creating a dynamic influenced by federal earnings and California’s progressive tax brackets. This means that for many Californians, Social Security is not tax-free as popularly assumed—quite the opposite.

The core of California’s Social Security tax policy hinges on combined income thresholds. The state evaluates total annual income by adding federal Social Security benefits to other taxable sources—such as wages, royalties, and rental income—before applying its 1% flat tax rate on the excess income above specific thresholds. “Post-retirement income in California is far from tax-free,” notes public finance analyst Linda Martinez.

“Even if federal benefits escape full taxation, California often taxes a portion based on how much claimants earn overall.”

According to California’s Revenue and Taxation Code, all forms of federal retirement income are subject to state tax if they push a retiree’s total income into a taxable range. For single filers, the 2024 federal threshold for partial taxation begins at $35,724 in Social Security income, while joint filers face the same threshold at $71,448. Any income above these figures becomes partially taxable, with the state applying a flat 1% rate.

However, the critical factor is not Social Security alone, but the sum of all income sources.

For example, a single retiree in California earning $60,000 annually from work and $18,000 from Social Security would see their total income sit just below the below-threshold level—rendering the Social Security portion largely untaxed. But someone drawing $80,000 in federal pensions alone—exceeding California’s $35,724 threshold—would have up to 1% of $44,276 ($3,927.76) withheld statewide.

California’s approach reflects its broader fiscal philosophy, relying on broad revenue bases rather than exemptions. The state collects substantial revenue from high-income residents through its graduated income tax system, and Social Security is not shielded by federal firewall provisions.

“California treats Social Security like any other income—a portion is taxed at the state level if it pushes your total earnings into a taxable bracket,” explains state tax attorney Mark Delgado. “This design discourages the false belief that federal benefits are inherently shielded in the Golden State.”

Importantly, not all Social Security benefits are taxable. The Karlsruhe Institute of Economics notes that up to 85% of benefits may be exempt for single filers with Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) below $23,000 or joint filers under $32,000.

Yet even exempt portions can affect California’s tax calculation because any taxable income—whether federal or state—feeds into the 1% assessment. For retirees near or above threshold levels, this interplay shapes net monthly cash flow significantly.

Taxpayers seeking clarity should model their projected income using California’s official tax withholding calculator, inputting both Social Security amounts and other earnings to estimate state liability. “We recommend detailed retirement income projections, not assumptions,” advises Delgado.

“California’s tax system rewards planning and transparency.”

Beyond individual case sensitivity, the policy underscores a broader tension between federal dells and state fiscal needs. While federal law protects retirement income from state taxation at the source, California’s progressive framework asserts its right to tax all income realized within its borders. This means that for retirees living in the state, Social Security may carry a hefty state tax burden—even though local policymakers across the U.S.

often champion tax-free retirement. The reality is not idealistic exemption, but calibrated economic contribution.

In practice, this means a Californian retiree with no other income may fare well under the system, but those supplementing Social Security with side income, investment dividends, or pensions face tangible state taxation. The state’s 1% levy on taxable excess income acts as a subtle but meaningful adjustment to retirement economics.

With increasingly complex income streams in modern retirement—such as rental synergies, part-time work, or faith-based employment—understanding these subtleties becomes essential.

To summarize, California does tax Social Security benefits, applying state income tax based on how federal and state earnings combine. The 1% flat rate applies to taxable income above defined thresholds, meaning no federal exemption guarantees full tax-free retirement income in the state. For Californians navigating retirement, this demands proactive financial planning—knowing total income, modeling tax liabilities, and understanding that Social Security is not automatically tax-free here.

The policy reflects California’s commitment to robust revenue generation, and while it may surprise new retirees, the framework is clear: economic presence warrants state taxation, regardless of federal origin.

As retirement income structures evolve, so too must public awareness. California’s stance on Social Security taxation is a model of how state policy shapes federal-retirement clarity—demanding transparency, planning, and respect for the interplay between federal benefits and California’s fiscal reality. In a world where tax logic often surprises, clarity on Social Security’s California liability empowers retirees to preserve wealth through informed decisions.

Related Post

The Unsent Project: A Deep Dive Into Unwritten Words and the Emotions That Never Find Their Destination

<strong>Lover Boy: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding the Modern Romantic Ideal</strong>

Mom CCTV: The Smart Surveillance Tool That’s Redefining Family Safety at Home

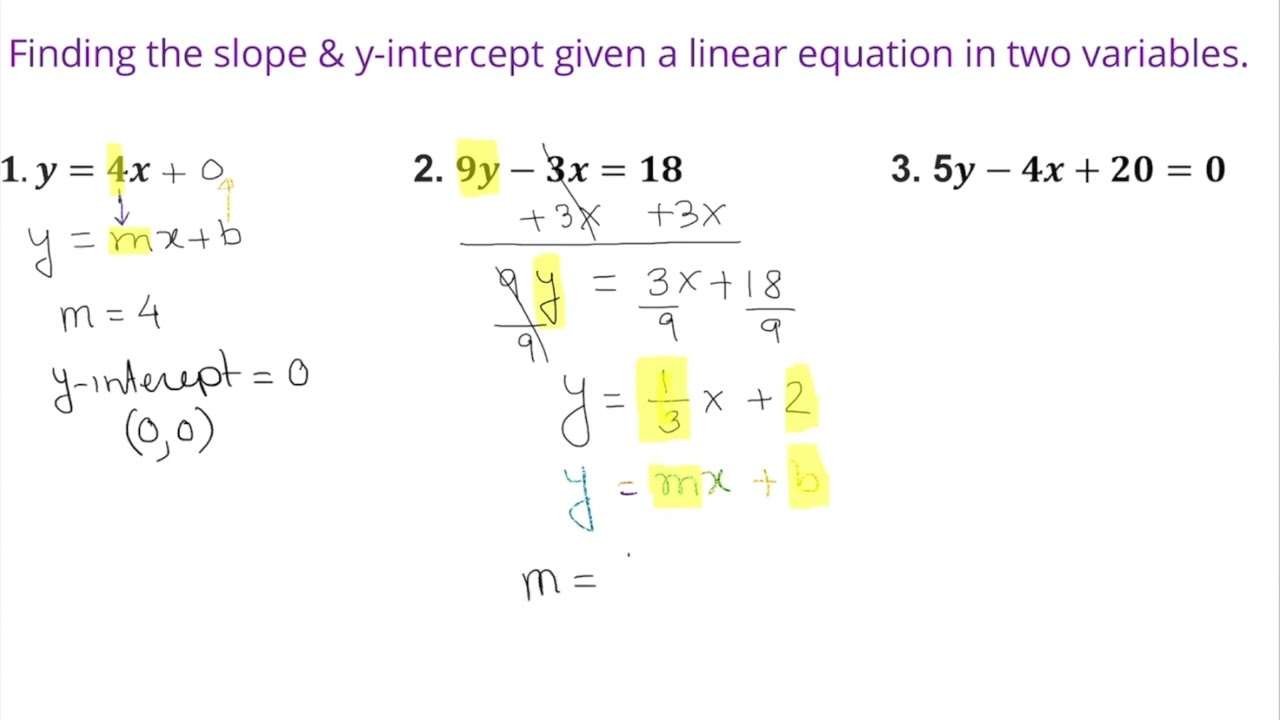

Master How to Find Y Intercept with Just Two Points: Your Step-by-Step Guide