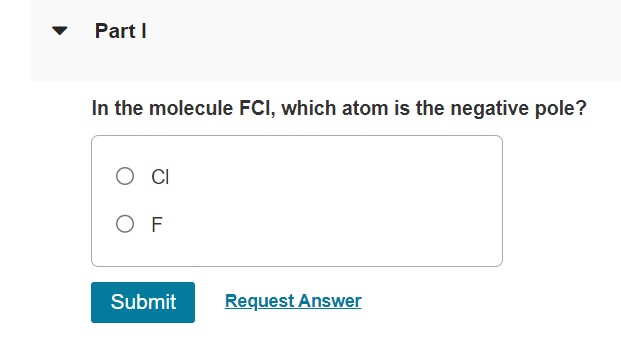

In The Molecule Bri: Which Atom Claims the Negative Pole?

In The Molecule Bri: Which Atom Claims the Negative Pole?

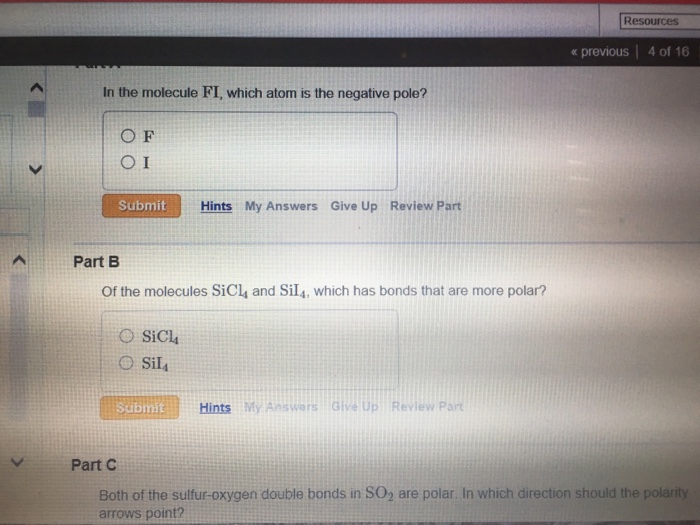

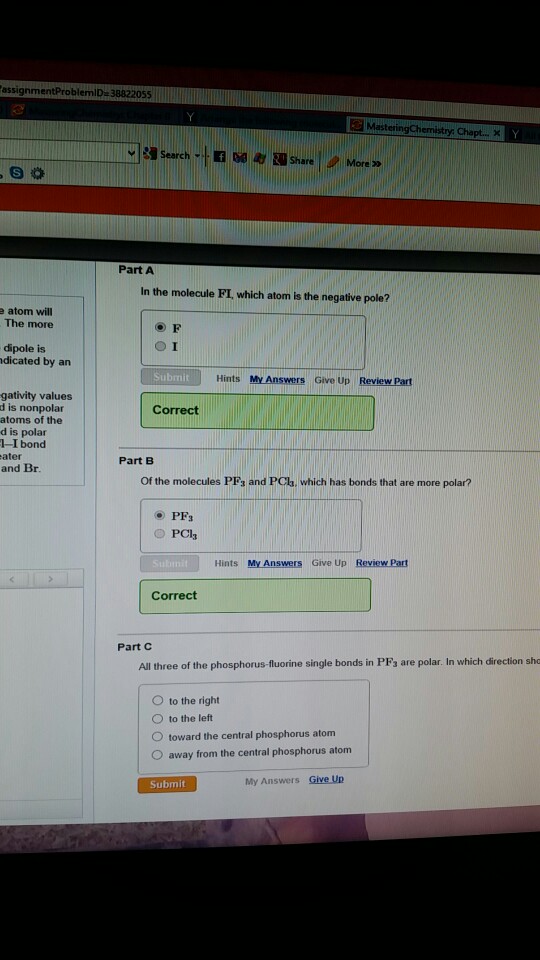

Understanding electronegativity reveals which atom steals electrons—and holds the charge. In the intricate world of molecular chemistry, one question echoes through classrooms and labs alike: Which atom bears the negative pole in a molecule? Often misunderstood, this role isn’t determined by atomic mass alone but by electronegativity—the ability of an atom to attract shared electrons in a chemical bond. Atoms like oxygen and chlorine, with high electronegativity, consistently pull electron density toward themselves, effectively claiming the negative side in polar bonds.

Yet, in a neutral molecule, stiffness and symmetry can neutralize charges, making the concept nuanced and frequently misleading. This article explores the atomic foundations of negative charge in molecules, illuminating electronegativity, bond polarization, and real-world molecular behavior.

The Electron’s Lighthouse: Electronegativity Defined

Electronegativity, though not explicitly quantifiable at the atomic level, serves as a predictive metric for how strongly atoms recruit electrons during chemical interactions.First rigorously mapped by Linus Pauling in the 1930s, electronegativity values are rooted in ionization energy and atomic radius—factors that determine an atom’s pull on its electron cloud. Pauling’s scale assigns fluorine the highest electronegativity (4.0), a reputation earned from its small size and high effective nuclear charge, enabling it to pull electrons with almost unmatched dominance. Measured on a 0–4 scale, hydrogen ranks lowest (~2.2), while heavier, more electronegative elements like nitrogen (~3.0) and oxygen (~3.5) dominate polar bond scenarios.

But electronegativity is more than a static number—it reflects dynamic electronic behavior. In a bond, the atom with greater electronegativity exerts a stronger pull, distorting electron density toward itself. This imbalance defines partial charges: a negative pole forms where electrons accumulate, while the less electronegative partner assumes a positive charge.

Polar Bonds: When Atoms Fight Over Electrons

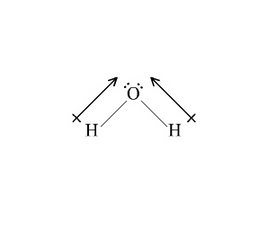

Polar covalent bonds arise when atoms differ significantly in electronegativity. Consider water (H₂O), a classic case. Oxygen, with electronegativity 3.5, draws electron density away from hydrogen atoms, each averaging 2.2.This gradient creates a bent molecule with two partial negative charges (δ⁻) on oxygen and two partial positive charges (δ⁺) on hydrogens. “The negative pole isn’t just symbolic—it’s a charge concentration zone,” explains chemical physicist Dr. Elena Torres.

“In H₂O, oxygen’s hold on shared electrons creates a dipole: one end rich in electron density, the other depleted.” This polarization drives hydrogen bonding, solubility of polar substances, and crucial biological functions such as protein folding and enzyme activity. Chlorine offers another instructive example. In hydrochloric acid (HCl), chlorine’s electronegativity (3.16) exceeds hydrogen’s (2.20), generating a strong polar bond.

When HCl dissociates in water, the Cl⁻ ion becomes stable in solution, carrying the molecular negative pole, while H⁺ contributes a secondary positive character.

The Illusion of Neutrality: When Science Meets Symmetry Not all molecules distribute charge evenly—even when individual atoms possess strong electronegativity. A molecule’s net polarity depends on both electronegativity differences and geometry.

Tetrahedral methane (CH₄) illustrates this perfectly: with four identical C–H bonds, electron distribution remains symmetric. Despite hydrogen’s lower electronegativity, the balanced arrangement cancels partial charges, rendering methane nonpolar and lacking a defined negative pole. Contrast this with ammonia (NH₃), where lone-pair repulsion distorts the ideal geometry into trigonal pyramidal.

The nitrogen atom, with electronegativity 3.0, draws electron density toward itself, creating a robust partial negative charge. This polarity makes ammonia miscible with water and critical in biological catalysis. Resonance structures further complicate charge localization.

Benzene, for instance, exhibits delocalized electrons across its ring, reducing net polarity despite each carbon-hydrogen bond showing slight electronegativity disparity. Thus, the apparent negative pole is often a temporary feature within a stabilized electron cloud.

Real-World Implications: From Cellular Processes to Material Science

Electronegativity-driven charge distribution is not mere academic interest—it commands real-world impact.In biological systems, protein function hinges on polar interactions: the negative poles on oxygen and nitrogen atom in amino acid side chains attract water, enabling solvation and structural folding. Enzymatic active sites rely on precise dipole orientations to bind substrates. In industrial chemistry, understanding polar bonds guides

Related Post

Unveiling The Truth: Unraveling The 'michael Hanley Horse Video Link

Bahwa: The Unwhispered Force Reshaping Health, Wellness, and Cultural Identity

Charles Lindbergh Field: The Gateway to Washington Reagan – A Critical Hub in Aviation History

Republika Srpska at a Crossroads: The Pulse of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s SMS