Is Bacteria Prokaryotic or Eukaryotic? The Foundational Biology You Need to Know

Is Bacteria Prokaryotic or Eukaryotic? The Foundational Biology You Need to Know

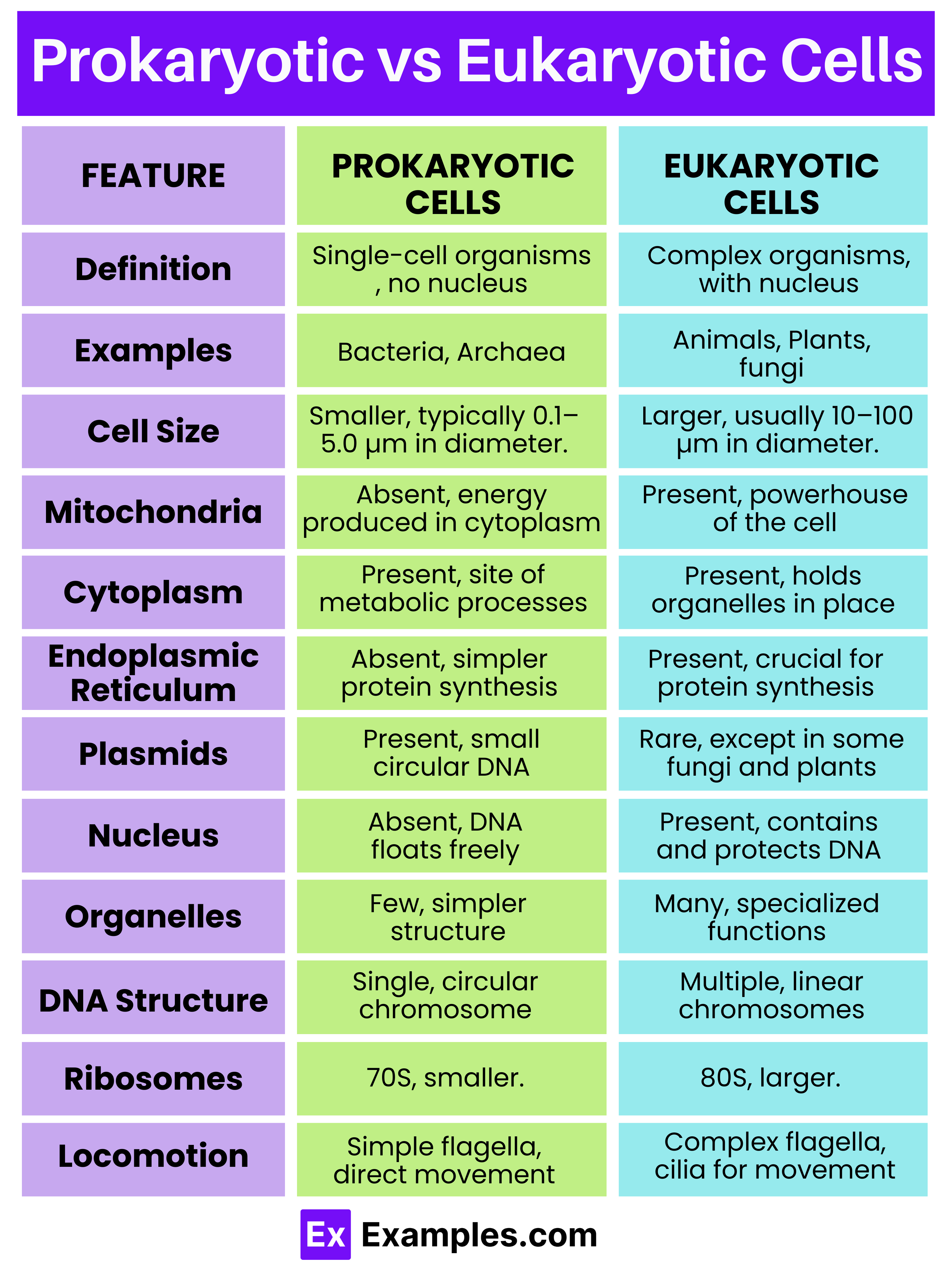

Bacteria defy simple categorization beyond strict prokaryotic classification—clear distinctions in cellular architecture set these ancient life forms apart from both eukaryotes and each other. Defining prokaryotic and eukaryotic life hinges on fundamental structural differences, and bacteria exemplify the strict prokaryotic blueprint with remarkable consistency across billions of years of evolution. While the terms “prokaryotic” and “eukaryotic” are often thrown around in biology, understanding their precise definitions—especially in the context of one of Earth’s most foundational life domains—reveals the depth of cellular diversity. Bacteria, as definitive prokaryotes, lack membrane-bound organelles and exhibit a cellular organization shaped by simplicity and efficiency.

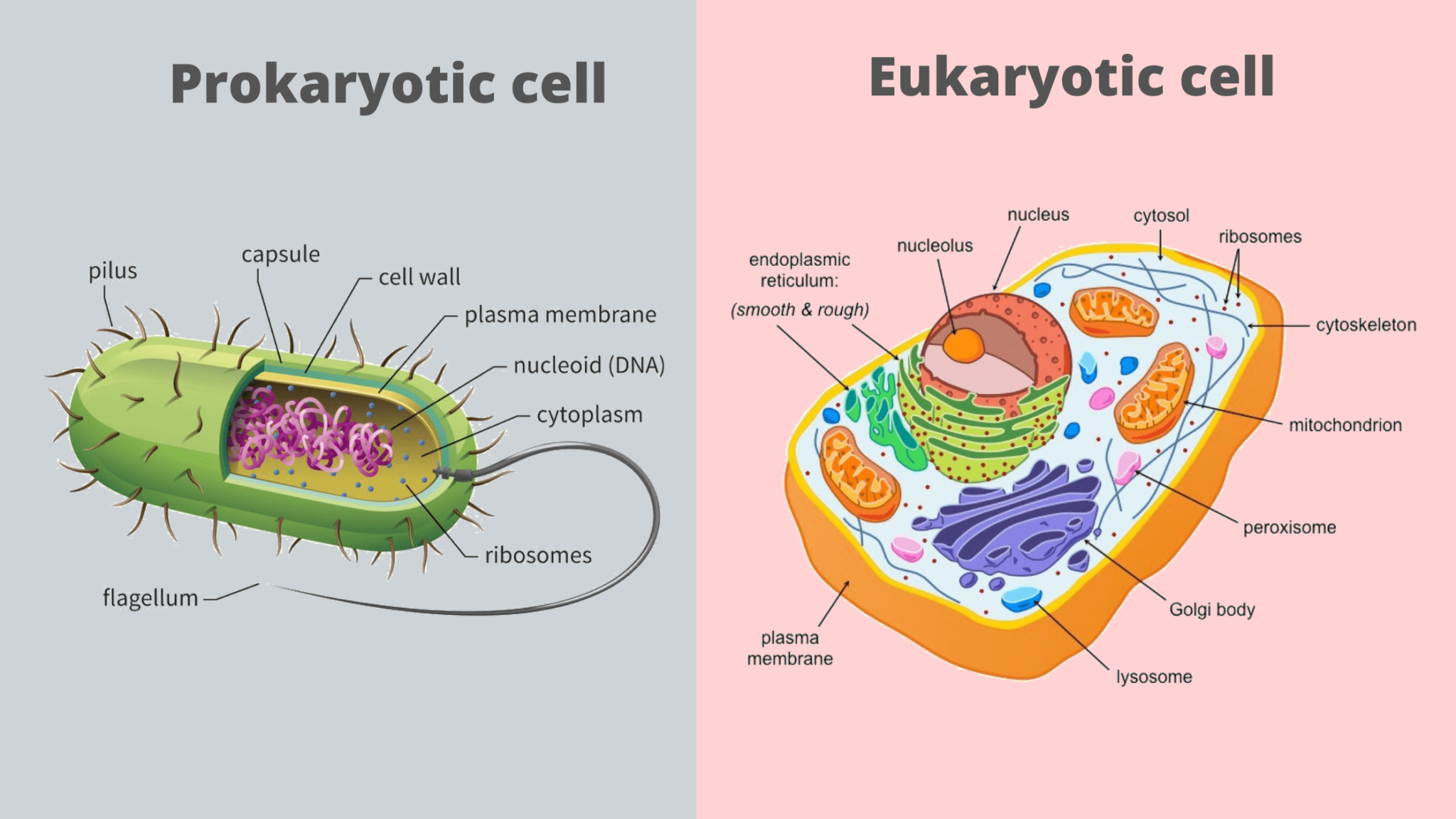

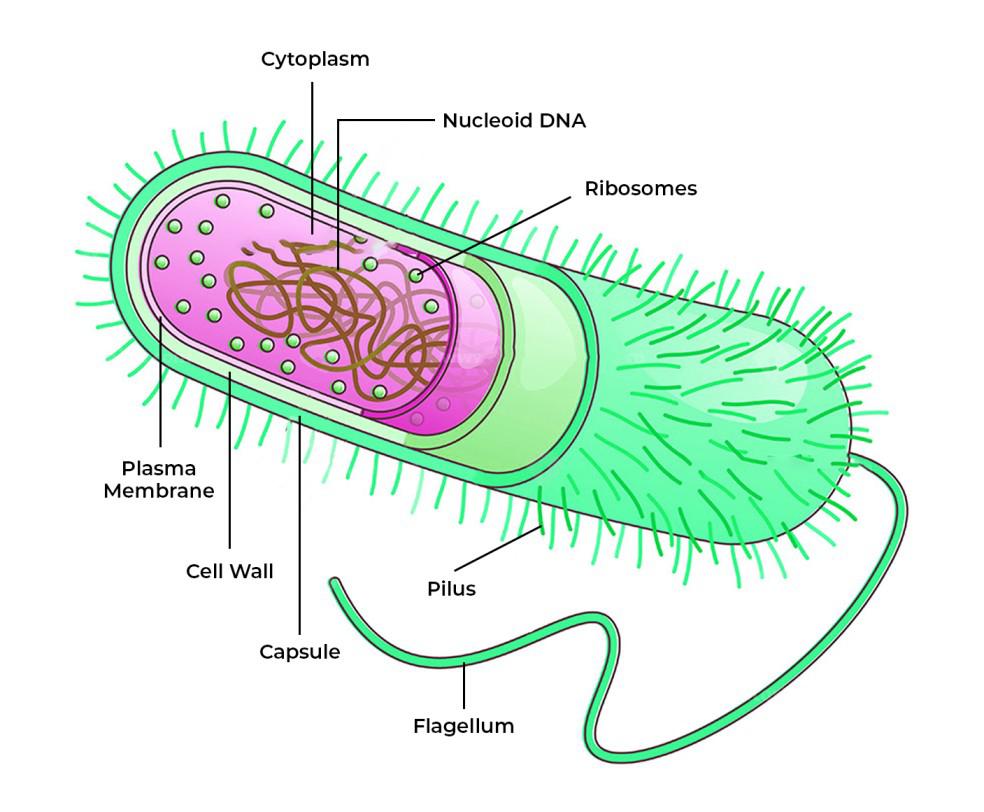

The defining hallmark of prokaryotic cells—like those of bacteria—is the absence of a nucleus. Instead, microbial forecasting tools and genomic studies consistently confirm that bacterial cells contain a single, circular chromosome floating freely in the cytoplasm within a region called the nucleoid. This arrangement lacks the protective nuclear envelope found in eukaryotic cells and underscores a streamlined genetic architecture.

Unlike eukaryotes, which compartmentalize functions through organelles such as mitochondria and ribosomes enclosed in membranes, bacterial cells rely on a minimal set of molecular machines. Resistance to environmental stress—now critical in antibiotic research—stems from this structural economy: no nuclear membrane to block drug penetration, no organelles to target selectively. Energy generation in bacteria, as documented in microbiology research, operates through simple yet sophisticated systems.

Many species generate ATP via aerobic respiration, using cytoplasmic membranes as the site for electron transport chains. Others thrive in anaerobic environments using fermentation or chemosynthesis—processes that reflect adaptations to extreme habitats from deep-sea vents to human gut linings. “The metabolic versatility of prokaryotes underscores their evolutionary success,” notes Dr.

Elena Torres, a microbial physiologist at the Institute for Applied Microbiology. “Their ability to harness diverse energy sources without rigid subcellular architecture sets them apart.” Reproduction in bacteria is predominantly asexual, primarily through binary fission—a tree-like process where one cell divides into two genetically identical daughter cells. This lack of sexual cycling contrasts sharply with eukaryotic reproduction, which often involves complex meiosis and genetic recombination.

Horizontal gene transfer further distinguishes bacterial evolution: plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes can leap between unrelated cells, accelerating adaptation in mere generations. Structurally, bacteria display striking diversity in form and function without implying complexity. They appear as rods (bacilli), spheres (cocci), or spirals (spirilla), each morphology reflecting functional specialization shaped by environment.

Pods of bacteria forming biofilms on medical devices or dental plaque exemplify how prokaryotic social behavior enhances survival—behavioral ingenuity rooted in ancient cellular principles. As research advances, the prokaryotic-eukaryotic divide remains central to understanding life’s complexity. Bacteria, though unicellular, reveal an intricate system of self-organization—membrane-less networks of proteins and RNA that dynamically organize cellular tasks in the absence of organelles.

“What makes prokaryotes so compelling,” argues Dr. Rajiv Mehta, a molecular biologist, “is not their simplicity per se, but how comprehensively they exemplify efficiency in cellular design.” This very efficiency has allowed bacteria to dominate Earth’s biosphere for over 3 billion years, influencing every ecosystem from soil to human microbiota. Understanding bacteria as unambiguous prokaryotes not only clarifies their biological status but also informs critical fields—medicine, biotechnology, and environmental science.

Their structural consistency enables precision in antibiotic targeting, while their evolutionary resilience highlights challenges in controlling disease and antibiotic resistance. More than a classification—being prokaryotic in bacteria means belonging to life’s earliest experiments in cellular organization, where minimalism enabled maximal adaptability. In a world of complex multicellular organisms, bacteria remain the paragon of prokaryotic elegance.

Related Post

Travis The Chimp: The Unlikely Star Redefining Animal Media and Conservation Engagement

How Tall Is the Average 6-Year-Old Boy? A Precise Look at Youth Stature

Unlock Test Success: How Answers Usa Test Prep Transforms Scores and Confidence

Weather for Edon, Ohio: Your Key to Navigating the Seasons in This Central Ohio Community