Master U.S. Coast Guard Navigation Rules: The Ultimate Cheat Sheet for Safe Vessel Operations

Master U.S. Coast Guard Navigation Rules: The Ultimate Cheat Sheet for Safe Vessel Operations

The U.S. Coast Guard’s Rules of the Road form the definitive guide for safe maritime navigation, ensuring vessels of all sizes avoid collisions and operate with clear, predictable conduct on shared waterways. These standardized principles, often distilled into compact checklists or cheat sheets, empower mariners—from weekend boaters to professional skippers—to navigate complex traffic patterns with confidence.

Whether steaming through busy harbors or sailing along open coastlines, understanding and applying these rules minimizes risk and protects lives. As the Coast Guard affirms, “Clear rules mean clear actions—especially when seconds count.”

Foundational Principles: Who Gives Way, Who Must Yield

At the core of the U.S. Coast Guard Rules of the Road are two fundamental doctrines: the principle of **giving way** and the obligation to **yield right of way**.These rules are not arbitrary; they are logically structured around vessel type, maneuverability, and situational awareness. - **New Rule vs. Existing Rule**: A vessel proceeding under a new course (e.g., crossing a course obstructing another vessel) must yield to any vessel that was already on a direct course toward that vessel.

This prevents reactive, panic-driven decisions and establishes a predictable chain of responsibility. - **Pilot-Powered Vessels**: Always yield to vessels under the control of a pilot, especially in congested waterways like ports or ferry channels. Pilots are authorized to enforce safer navigational discipline.

- **Power-Assisted Vessels**: These include boats with engines or feelers, defined as “motor vessels” under Coast Guard guidelines. When encountering non-powered vessels (e.g., sailboats, canoes), power-driven craft generally have priority unless obstructing a safe crossing. As noted in the official cheat sheets, “When in doubt, look to the right—then assess your speed, your route, and your ability to stop—to determine whether yield is required.” This principle-based logic underpins safe navigation across varying maritime environments.

Vessel Classification: Speed, Size, and Responsibility

The Coast Guide categorizes vessels into four key classes based on speed, maneuverability, and surveillance requirements: vessels with distinct responsibilities that shape their navigational roles. - **Power-Driven Vessels (Primary Movers):** Typically faster and harder to stop, these vessels—such as motorboats, yachts, and cargo craft—must maintain higher vigilance. They are required to avoid crossing vessels on a direct course or trailing vessels in restricted traffic zones.- **Sailing Vessels and Boats Under Sail:** Historically granted right of way in certain contexts due to limited speed and maneuverability. However, modern rules now emphasize caution—these vessels yield when crossing, but do not automatically yield if on a parallel or crossing course at a safe distance. - **Non-Motored Vessels (Ownership Implications):** Canoes, kayaks, and rowboats are considered “slow, non-power vessels.” While not legally obligated to yield in all situations, excellent mariners treat them as potential sources of unpredictability and yield when practical.

- **Tow Vessels and Slow Moves:** Vessels towing boats or barges must account for reduced control, often slowing or snubbing engines to minimize risk. Their presence demands heightened caution from other vessels. A critical clause in the Rules of the Road states: “Slow craft cannot stop quickly—adjust course and reduce speed when navigation requires caution.” This underscores that speed and maneuverability define responsibility, not just size.

Crossing Scenarios: Decoding the Right-of-Way Hierarchy

One of the most critical applications of U.S. Coast Guard rules lies in crossing maneuvers—situations where two vessels approach each other on intersecting paths. Properly applying these rules prevents confusion and collision.- **Crossing at a Right Angle:** The vessel crossing another on a perpendicular course yields. If both vessels are moving forward, the one crossing must slow or alter course to allow safe passage. - **Crossing from Starboard to Port:** Typically, the vessel on the starboard side has right-of-way, but only if both are moving steadily and not crossing at an angle.

In ambiguous angles or reduced visibility, yield to avoid risk. - **Crossing at an Oblique Angle:** Here, speed and relative proximity dictate priority. The vessel moving faster or on a sharper crossing path bears responsibility, unless both vessel masters assess and adjust accordingly.

The Coast Guard warns: “Angles matter, but intent matters more—use course, speed, and context to determine who should yield.” Mariners should continuously scan surroundings, maintain situational awareness, and communicate intent through proper signaling or cabin voice.

Navigation Aids & Signaling: Communicating Intent Clearly

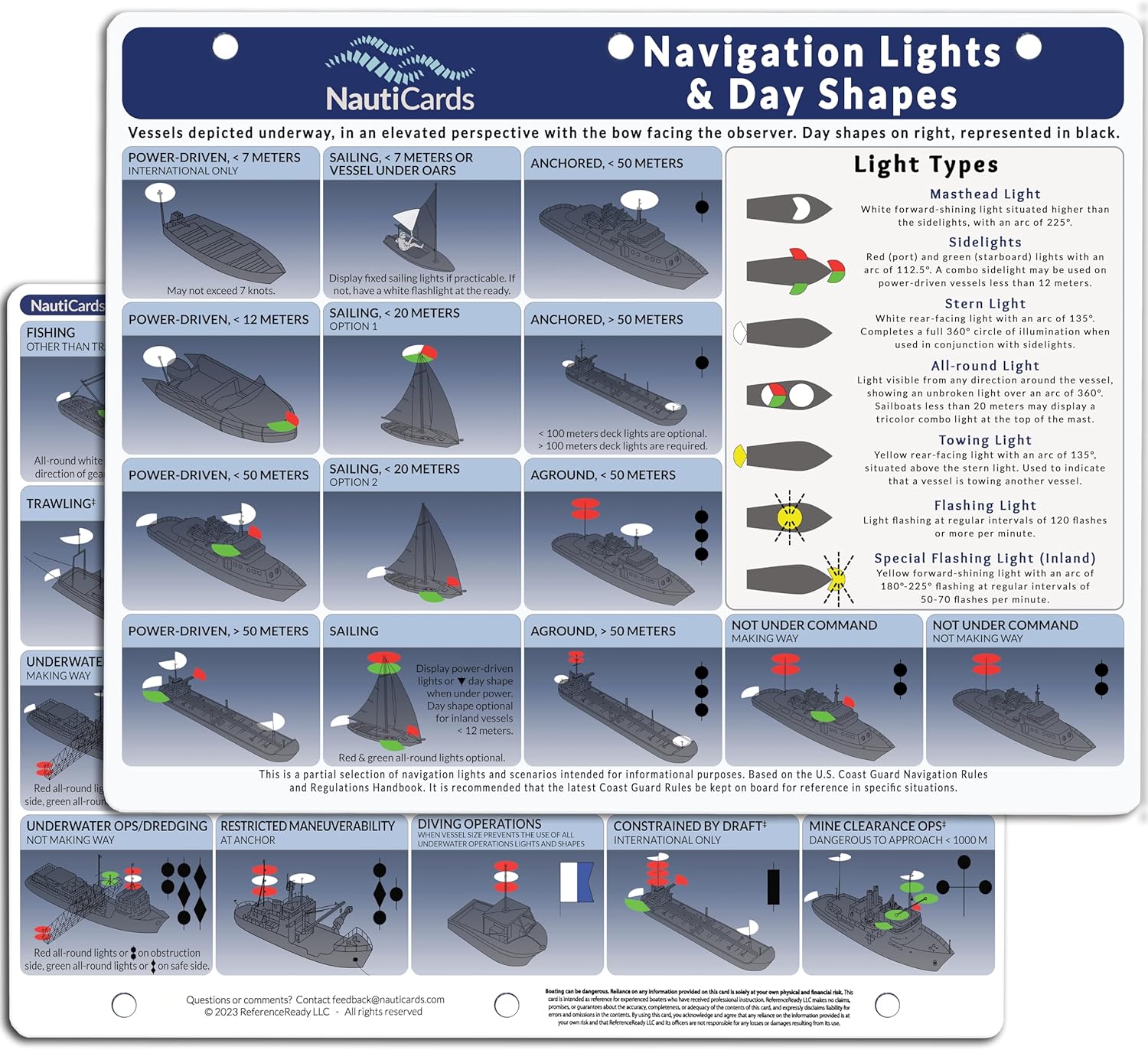

Communication, both visual and electronic, is pivotal in avoiding misunderstandings. The U.S.Coast Guard’s Rules of the Road emphasize clear signaling to clarify maneuver intention. - **Nautical Signals by Day and Night:** Luminous daybeacons, radars, and aerial signals (flares, light lanterns) provide visual cues. Each signal conveys speed, direction, and course intentions—yellow lanterns for starboard, green for port.

- **Radio and Electronic Reporting:** In high-traffic zones or inclement weather, radio alerts (e.g., “Mayday,” “Pan-Pan”) and AIS (Automatic Identification System) confirm vessel identity and trajectory, reducing ambiguity. - **Hand Signals for Close Quarters:** When radio fails, traditional signals—flag declarations, pistol shots (non-lethal), bi-buccaneers—remain essential for clarity during rare close encounters. Effective signaling transforms potentially hazardous situations into coordinated movements: “A single light tells a story—master your signals to turn confusion into clarity.”

Situational Awareness: The Human Element in Rule Application Technology supports navigation, but human judgment remains irreplaceable.

Even with advanced radar and GPS, mariners must interpret data within real-world context. - **Visibility Limits:** Fog, dusk, or glare reduce reaction time. Under such conditions, slow speed, use of sound signals, and maintaining vigilant lookout are mandatory.

- **Mariner Fatigue:** Long hours impair perception and response. Regular rest, crew rotation, and acknowledgment of fatigue are

Related Post

Celebrity Movie Archive Reveals Alist Stars’ Most Shocking On-Screen Transformations: When Stars Shocked the World

Pompano Fish: The Silent Tournament Champion of the Ocean’s Fastest Predators

26 Court St Brooklyn: Where History Meets Modern Urban Pulse

Deciphering the Arcane Chart: The Ultimate Fate Series Watch Order Explained