Meiosis I and II: The Precise Dance of Cell Division That Shapes Life

Meiosis I and II: The Precise Dance of Cell Division That Shapes Life

At the heart of genetic diversity and species survival lies a meticulously orchestrated process: Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division that transforms diploid germ cells into haploid gametes. Spanning two distinct phases—Meiosis I and Meiosis II—this biological mechanism ensures the faithful reduction of chromosome number, enabling sexual reproduction while safeguarding genomic integrity. far from a passive share of genetic material, meiosis employs a sequence of precisely timed divisions to separate homologous chromosomes in Meiosis I and sister chromatids in Meiosis II, laying the foundation for evolutionary continuity.

Meiosis I: The Architect of Chromosomal Reassembly

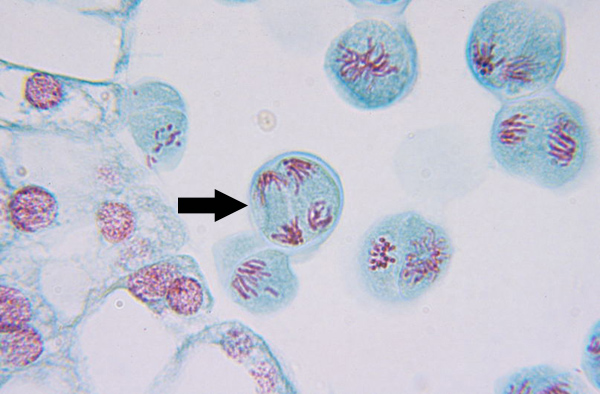

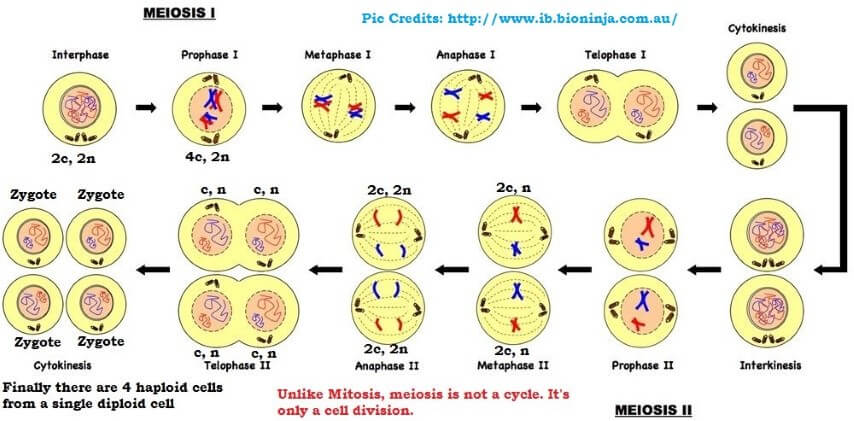

Meiosis I marks a pivotal transformation in which homologous chromosomes—paired counterparts originating from distinct parental sources—are segregated into separate daughter cells. This phase halts at prophase I, a complex and extended stage rarely observed in ordinary mitosis, and is distinguished by the formation of the synaptonemal complex, a protein spindle-like structure that aligns sister chromatids of homologous pairs. In prophase I, chromosomes condense and undergo a revolutionary process known as crossing over.

During pachytene, homologous chromosomes briefly associate in intimate contact through structures called chiasmata, facilitating the exchange of genetic material across non-sister chromatids. “This recombination shuffles alleles across homologous regions, generating novel genetic combinations without altering total DNA content,” explains geneticist Dr. Elena Rostova from the Institute of Molecular Biology.

As meiosis I progresses, chromosomes reach metaphase I and align at the equatorial plate. Spindle fibers from opposite poles then pull homologous pairs toward opposite poles during anaphase I, though sister chromatids remain connected and continue moving together—unlike in Mitosis, where individual chromosomes segregate. This unequal division is fundamental: it reduces a diploid cell (2n) into two haploid cells (n), each containing a unique mix of maternal and paternal chromosomes.

Two key features define Meiosis I: • **Homologous pairing:** chromosomes align in tetrads, increasing genetic variability through recombination. • **Homologous chromosome separation:** only one chromosome from each homologous pair enters each daughter cell. Defects in Meiosis I can disrupt gametogenesis, contributing to infertility or conditions like nondisjunction, which often leads to aneuploidies such as Down syndrome.

“Errors early in meiosis are among the most consequential genetic mistakes,” reiterates Dr. Rostova, emphasizing the phase’s critical role in reproductive health.

Meiosis I thus stands not merely as a division step but as the cornerstone of genetic diversity, where recombination and proper chromosome segregation conspire to break patterns of inheritance and nurture evolutionary adaptability.

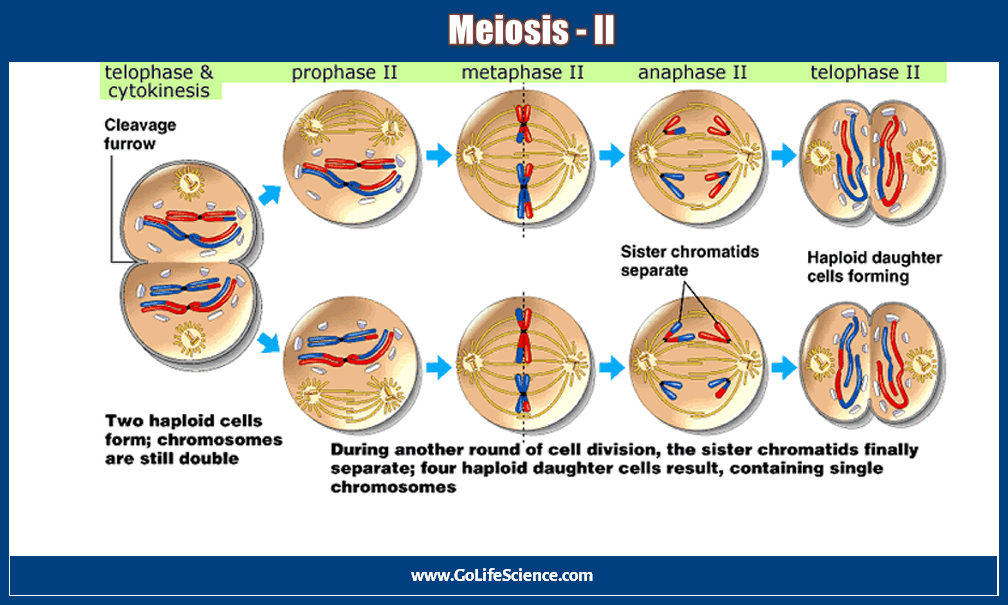

The Sequential Precision of Meiosis II: Completing Chromosome Division

Following Meiosis I, Meiosis II unfolds with remarkable similarity to Mitosis but with a crucial distinction: sister chromatids—already divided in Meiosis I—are now separated.This phase ensures each resulting gamete contains a single copy of each chromosome, fully haploid and genetically unique. Meiosis II begins in talit rem قد approaches: • Cells exit telophase I and enter a brief interkinesis, during which DNA replication occurs but no new chromosome material is synthesized. • At metaphase II, chromosomes align at the equator, each composed of two joined sister chromatids held together at the centromere.

• Anaphase II follows, with spindle fibers from both poles pulling chromatids apart toward opposite poles—this final separation completes the reduction from diploid to haploid. The result is four mature gametes, each with a distinct combination of alleles shaped by recombination and independent assortment in Meiosis I. Unlike Mitosis, which preserves genetic consistency, Meiosis II executes a precise division of sister chromatids, eliminating redundancy and ensuring genomic purity in gametes.

Crucially, while Meiosis I establishes the foundation by separating homologous chromosomes, Meiosis II enforces fidelity through chromatid cleavage—illustrating how each stage contributes indispensable roles to balanced inheritance. “The synergy between Meiosis I and II is a textbook model of biological efficiency: one phase orchestrates genetic shuffling, the other secures faithful distribution,” notes Dr. Rostova, reinforcing the phase-specific specialization as central to life’s replication.

Taken together, Meiosis I and II form an elegant, multi-stage process that transcends simple cell division. Through controlled chromosome pairing, homologous segregation in Meiosis I, and sister chromatid separation in Meiosis II, this division cycle preserves species’ genetic stability while fostering variation—essential for evolution and biodiversity.

The story of life’s continuity is written in the elegant choreography of Meiosis I and II: a sequence of divisions that balances assembly and fragmentation, inheritance and innovation. From the recombination hotspots of prophase I to the final cleavage of sister chromatids, each step ensures gametes are distinct, viable, and ready to partner in the next generation.

As science delves deeper into the molecular intricacies of meiosis, its role in fertility, inheritance, and disease prevention continues to grow—making this phase not just a biological process, but a cornerstone of life itself.

Related Post

Maurice Jones-Drew and the Jaguars: Age, Wife, and the Journey Behind the Jaguars’ Nuclear Core

Esale Ikco Ir: A Comprehensive Guide to Mastery and Mastery-Driven Success

Unveiling The Truth Behind Eileen Davidson’s Farewell From 'The Young and the Restless' — A Final Chapter After Three Decades

How Much Is Jason Bateman Worth Today? A Deep Dive into the Hollywood Star’s Net Worth