Orson Hodge: Architect of Acoustical Mastery in Concert Halls Across the Globe

Orson Hodge: Architect of Acoustical Mastery in Concert Halls Across the Globe

When it comes to shaping the subtle world of sound within engineered spaces, few figures stand as distinctly as Orson Hodge. This pioneering architect and acoustical engineer redefined how concert halls are designed, merging artistic vision with scientific precision to create spaces where music breathes and audiences feel every nuance. His work represents a rare fusion of technical innovation and aesthetic sensitivity, resulting in performance venues that remain benchmark-tested decades after their completion.

Precision Meets Passion: The First Glimpse into Hodge’s Legacy Hodge’s early career in the mid-20th century coincided with a golden age of concert hall construction, where architects began to recognize acoustics not as an afterthought, but as a foundational design element. Trained in both engineering and architecture, he approached sound like a sculptor treats clay—malleable, fractionally sensitive, and demanding patience. His breakthrough came with the 1950s renovation and expansion of Boston’s Symphony Hall, one of America’s most revered acoustic environments.

Working under the guidance of renowned acoustician Paul E. G. Julliet, Hodge didn’t merely preserve the hall’s legendary warmth; he refined it through meticulous adjustments to ceiling curvature, wall surface materials, and stage reflectors.

This period cemented his reputation as a master of sonic clarity and spatial resonance.

The hall’s signature "shoebox" shape, long praised for even sound distribution, became further optimized under Hodge’s direction. He introduced engineered wooden panels and adjustable acoustic diffusers, allowing subtle calibrations without altering the hall’s historic aesthetic.

As Hodge once stated in a 1961 interview with _Acoustical Society of America Bulletin_: “A concert hall is not just a room for instruments—it’s a living vessel for sound, shaped by geometry, material, and the intention behind every joint, seam, and surface.” These principles became the cornerstone of his methodology.

Engineering Emotion: The Science Behind Hodge’s Designs

Hodge’s approach diverged sharply from purely aesthetic or structural priorities. He treated acoustics as a calculated art.By employing early computational modeling—remarkable for the era—he simulated sound propagation and reverberation time to predict how music would travel through a space. His use of high-density wood, carefully angled plaster, and modulated surface textures minimized undesirable echoes while enhancing harmonic richness.

Key to his philosophy was the belief that materials themselves could “sing” with the music.

Hodge often specified spruce, cedar, and maple not only for durability but for their resonant properties—each amplifying specific frequency ranges. In interviews, he emphasized: “The wood in this hall isn’t just structure; it’s a mediator, vibrating in time with the instruments, catching overtones, and returning them clearer than any electronic system.” This tactile understanding of material science transformed concert halls from static venues into responsive, dynamic environments.

Global Impact: From Boston to Beyond

Hodge’s influence extended well beyond New England.In the 1970s and 1980s, he advised on landmark projects across North America and Europe, including the renovation of London’s Royal Albert Hall and the design of Vancouver’s Queen Elizabeth Theatre. His collaboration with European architects in the 1980s on the renovation of Berlin’s Philharmonie North wing introduced Nordic minimalism fused with state-of-the-art acoustic tuning.

In each project, Hodge insisted on site-specific solutions rather than one-size-fits-all approaches.

His 1983 work on Osaka’s Suntory Hall required innovative rainwater-inspired diffusers to counteract high humidity’s impact on sound, a testament to his adaptability and commitment to cultural context. By tailoring designs to local climate, geometry, and musical traditions, Hodge ensured that each venue honored both global acoustical standards and regional identity.

Lessons from a Master: What Remains of Hodge’s Philosophy Today

Though Orson Hodge passed in 1990, his principles endure as foundational in contemporary architectural acoustics.

Modern concert halls—from Sydney Opera House’s refined renovations to Seoul’s State Opera House—carry forward his integration of scientific rigor and artistic foresight. Today’s engineers use advanced digital modeling tools, yet the core challenge remains: designing spaces where sound is not just heard, but felt.

Key takeaways from Hodge’s legacy include:

His work redefined the relationship between space and music, proving that architecture, when guided by acoustical truth, becomes a silent partner in artistic expression. Orson Hodge did not merely design halls—he engineered experiences where sound becomes memory, and every performance resonates deeper than the artist intended.

Related Post

Discovering The Life And Achievements Of Symone Blust: A Trailblazer in Innovation and Advocacy

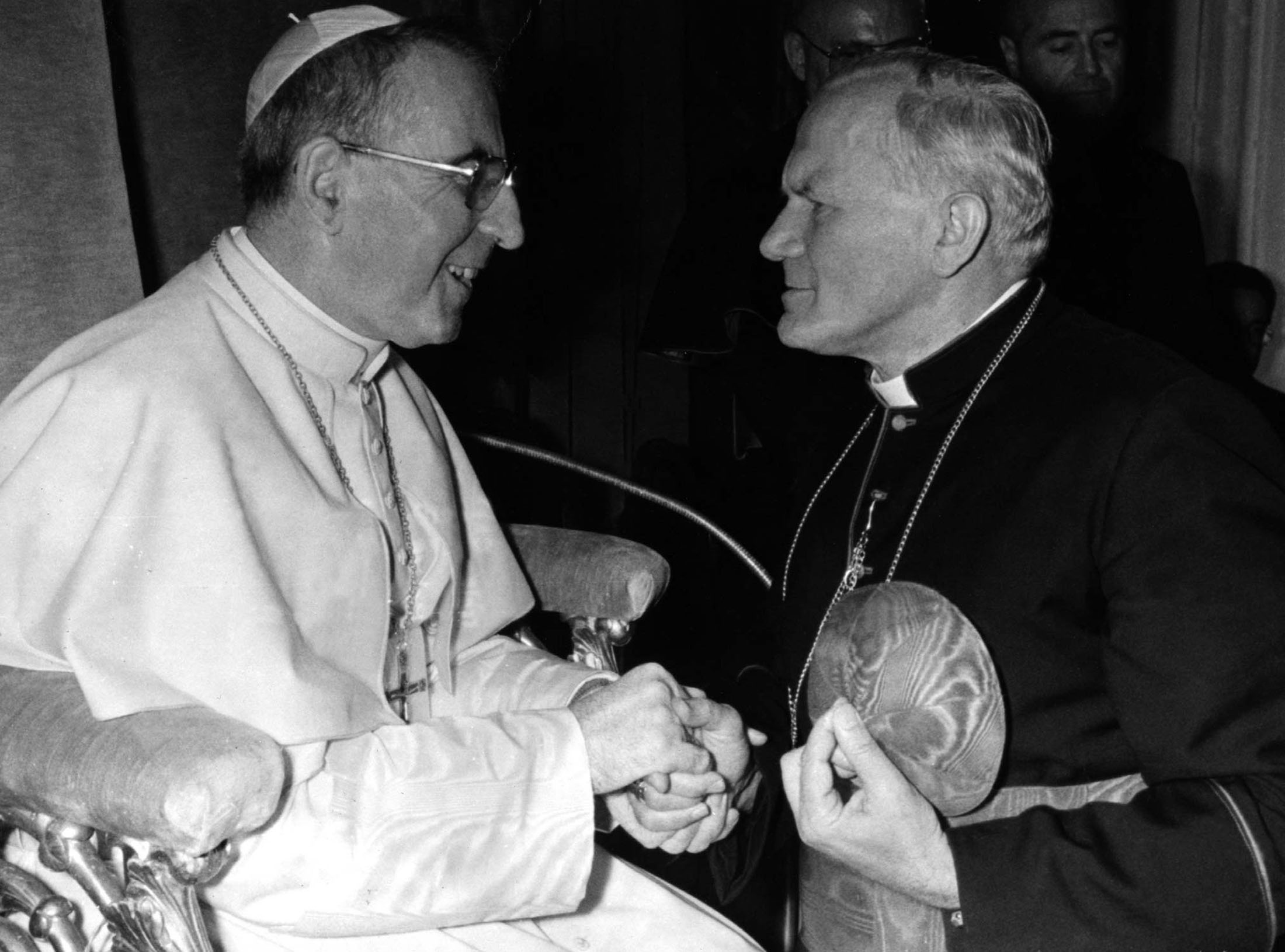

Pope John Paul II’s Path to Sainthood: A Soul Forged in Courage and Mercy

A Renaissance Rebel: Emma Watson’s Bik by Bik Reimagines Sustainable Elegance

/sarah-palin-1-cd38efac4aba4a189c5d3065696732a2.jpg)

Where Does Sarah Palin Currently Live in 2024? A Full-Life View of the Alpha State Politician’s Home Life