Religious Tapestry of Africa: Where Ashanti Sacred Traditions Meet Swahili Islam and Bantu Spiritual Realities

Religious Tapestry of Africa: Where Ashanti Sacred Traditions Meet Swahili Islam and Bantu Spiritual Realities

Africa’s spiritual landscape is a mosaic of ancient faiths, where the Ashanti’s rich Bantu cosmology coexists with coastal Swahili Islamic practices and the deeply rooted traditions of Arab-influenced communities. This intricate religious map spans from the forested hills of Ghana to the coastal citadels of Tanzania, weaving together mutual histories, cultural exchanges, and enduring spiritual identities. Far more than a geographic spread, this convergence reveals how religion shapes—and is shaped by—ethnic identity, trade, and political dynamics across the continent.

At the heart of West Africa’s spiritual identity lies the Ashanti people, a powerful Bantu-speaking group whose religious traditions are deeply interwoven with daily life. Central to Ashanti cosmology is the belief in Nyame, the supreme sky god, and the ancestral spirits known as *Abosom*. The Ashanti view their world as animated by spiritual forces, where rituals, sacrifices, and sacred symbols—such as the iconic *golden stool*—serve as vital conduits between the human and divine realms.

“Our religion is not just worship; it’s the grammar of existence,” explains Dr. Efua Mensah, an ethnographer at University of Ghana, emphasizing how spiritual practice guides leadership, agriculture, and social cohesion. The Ashanti system emphasizes ancestral veneration, with elaborate ceremonies marked by drumming, dance, and libations to honor forebears and ensure well-being.

Swahili Coast: Islam as Coastal Identity and Cultural Exchange

Along Africa’s eastern seaboard, the Swahili people represent a distinct spiritual trajectory—Arab-Muslim influence fused with Bantu roots to shape a unique coastal faith. Stripated from the Indian Ocean trade routes, Swahili cities like Zanzibar, Mombasa, and Kilwa evolved into cosmopolitan hubs where Islamic jurisprudence, architecture, and Arabic calligraphy became inseparable from local identity. Yet, this Islam is deeply contextual—blended with pre-Islamic customs and Bantu social structures.“Our Islam breathes the spirit of both the desert and the sea,” notes Fatuma Binti, a Swahili scholar at Igavere University, underscoring how prayer, pilgrimage, and communal life are interlaced with ancestral memory and community trust.

Islam arrived along these shores by the 7th century, carried by Arab and Persian merchants, but took root through sustained interaction with Bantu-speaking communities. The Swahili language itself bears the imprint of Arabic, with religious texts often rendered in a lexicon steeped in maritime trade, social ethics, and Sufi mysticism.

As practiced today, Swahili Islam includes veneration of saints (*walipindi*), elaborate coastal festivals like Mwaka Kogwa, and the integration of Islamic law with customary *jamaa* (village) governance. This synthesis creates a spiritual landscape where muezzins lead morning calls from ornate minarets, and coastal communities blend Qur’anic recitations with coastal folk rhythms. For the Swahili, religion is not distant—it pulses through markets, boats, and communal gatherings.

Bantu Spiritual Underpinnings: The Sacred Geographies of Ashanti and Beyond

Beneath the surface of diverse African faiths lies a shared Bantu spiritual foundation, particularly embodied by the Ashanti and related groups. The Bantu worldview places sacredness in nature—mountains, rivers, and forests are not inert but spirit-filled realms. Rituals honor deities like *Nkai* (the earth mother) and *Oku* (the river spirit), with daily offerings maintaining balance between the visible and invisible worlds.“Every hill has a story, every tree a guardian,” explains oral historian Kwesi Duuru, highlighting how geography is spiritual geography.

In Ashanti territory, sacred groves function as living temples—dense forests protected by taboos and priestly custodianship. Here, the *Odwira* festival renews cosmic order through purification rites, drumming, and ancestral remembrance.

“These spaces are not just protected; they are actively sustained,” Duuru continues, noting that even modern Ashanti society balances urbanization with ancestral duty. Other Bantu groups across Central and Southern Africa maintain similar principles: spiritual authority often vests in designated *abosom* (spirit mediums), whose roles bridge the practical and mystical.

Religious Syncretism and Enduring Legacies in a Changing Africa

Despite colonial divides and religious expansion, Africa’s spiritual map remains fluid.In many regions, Ashanti traditions persist alongside Islam and Christianity, manifesting in syncretic practices. Some rural communities invoke *Abosom* before Christian prayers, while urban Swahili neighborhoods blend Islamic festivals with Bantu-inspired dance. This layering is not contradiction but adaptation—faith as an evolving narrative shaped by history and daily life.

Scholars caution against viewing African religion through a static lens. “Religion in Africa is alive—negotiating identity, migration, and modernity,” asserts Dr. Amina Nkosi, a religious studies expert at the University of Nairobi.

Whether through the Ashanti’s ancestral drums echoing in Ghana’s forests, the Swahili’s sea-faring mosques crowned with coral, or the deep Bantu reverence for land and spirit, Africa’s spiritual tapestry endures as a testament to cultural resilience and deep-rooted meaning.

In Africa’s religious landscape, no single faith dominates—but together, they form a living continuum, where every ritual, place, and story invokes the sacred across Bantu forests, Ashanti hills, and Swahili shores.

Related Post

Popeyes Blackened: Where Flame Meets Southern Soul in a Daring Culinary Revolution

Play Android Games with Keyboard & Mouse: Your Ultimate Gaming Evolution

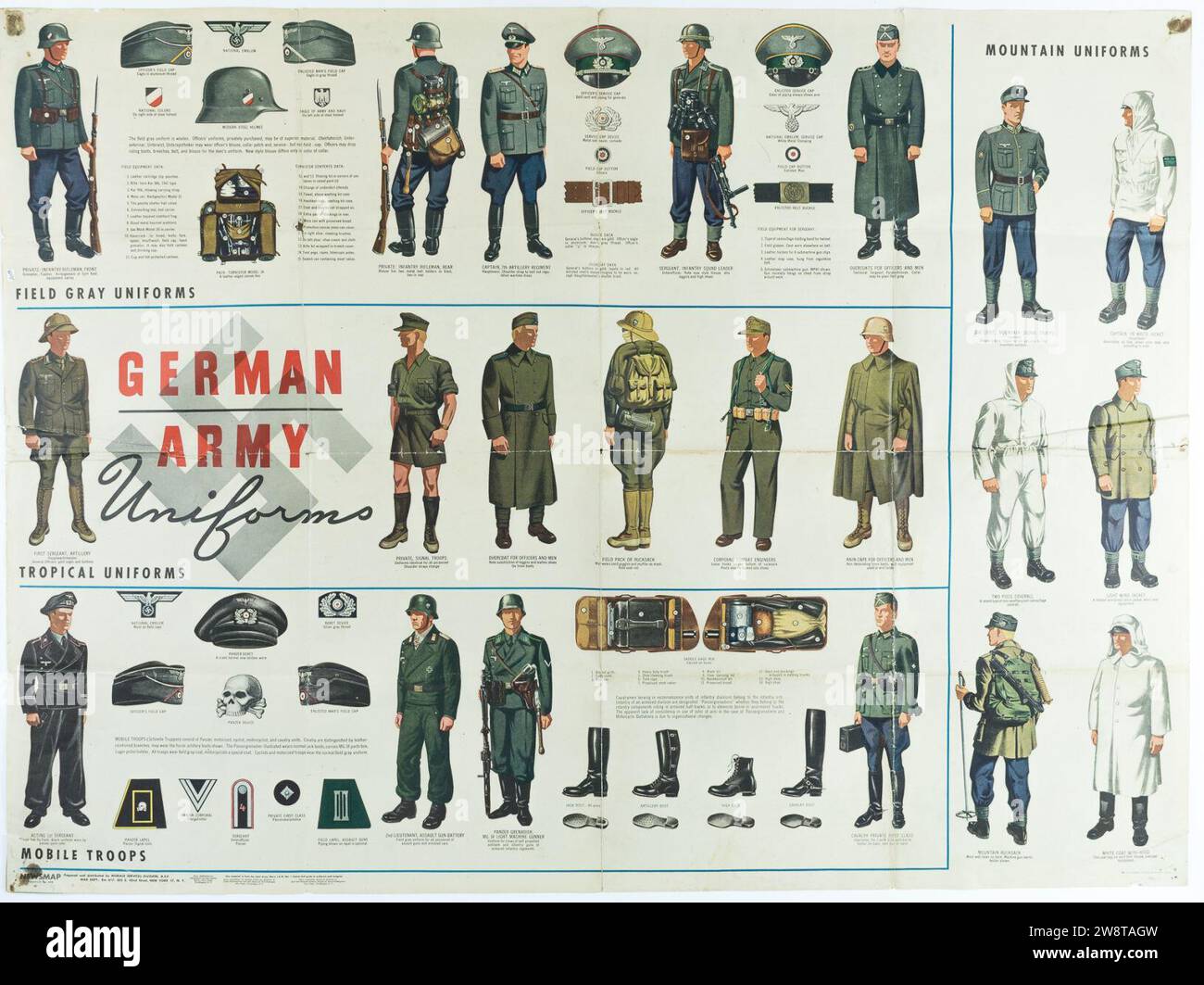

German Uniforms of World War Two: The Uniforms That Defined a Hidden Face of War

How Tall Is Rhett And Link? The Star-Crossed Duo’s Stature Revealed