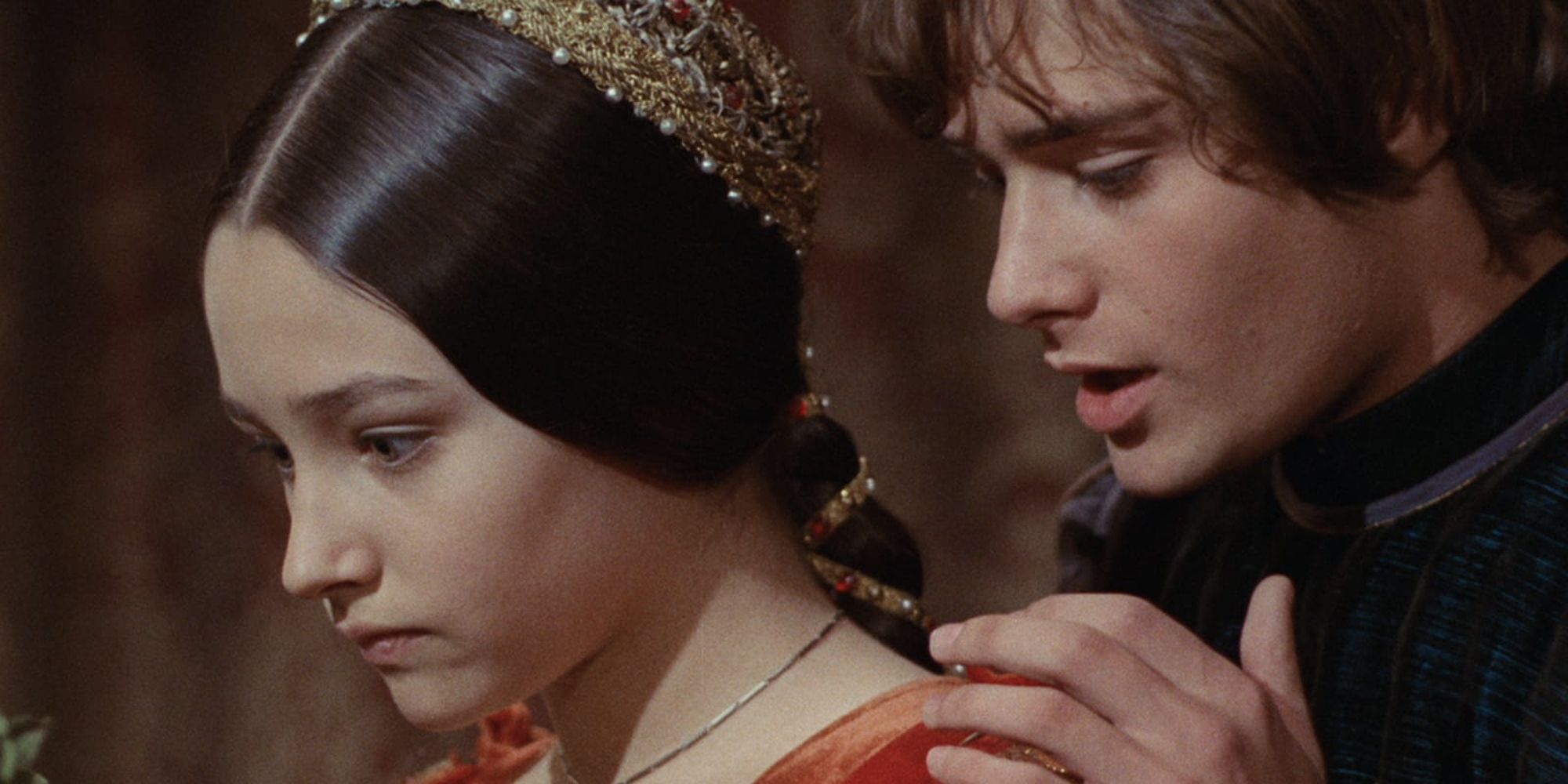

Romeo and Juliet (1968): Shakespeare’s Timeless Tragedy Reborn on the Silver Screen

Romeo and Juliet (1968): Shakespeare’s Timeless Tragedy Reborn on the Silver Screen

When Carol Reed’s 1968 adaptation of *Romeo and Juliet* hits the screen, it delivers not merely a retelling of Shakespeare’s iconic tragedy, but a haunting, visually arresting cinematic experience that resonates with raw emotional power. Adapted from the original play but reimagined with stark realism and a tempered color palette, this film stands as a pivotal interpretation—one that balanced fidelity to Elizabethan drama with stark modern sensibilities. It transported the feuding Montagues and Capulets from the streets of Verona to a gritty, sun-baked Mediterranean, grounding Shakespeare’s timeless悲剧 in a tangible, nearly documentary-like texture.

The film’s restrained yet evocative style, combined with Marlon Brando’s magnetic performance as Romeo, redefined how classic literature could be visualized for post-war audiences hungry for authenticity and psychological depth. At the heart of the 1968 adaptation lies a staggeringly committed cast, led by Marlon Brando in the titular role and Laurence Olivier as Lord Capulet. Brando, already legendary for his “method” intensity, brought a vulnerability and restrained passion to Romeo that diverged from traditional stage grandeur. His portrayal emphasized youthful impulsiveness and emotional fragility, amplifying the character’s inner turmoil rather than projecting romantic heroism. “My Romeo wasn’t a poet—he was a boy lost,” Brando explained in contemporary interviews, capturing the role’s raw authenticity. Opposite him, Olivier’s Capulet exudes aristocratic authority and quiet sorrow, lending gravitas to the family’s pride and the weight of intergenerational conflict. Their dynamic formed the emotional nucleus, magnetic yet grounded in naturalistic acting—a radical choice in a decade where stage-trained performances still dominated Hollywood epic cinema. Carol Reed, famed for *The Third Man*, brought his signature chiaroscuro lighting and theatrical lighting sensitivity to *Romeo and Juliet*, but with a stark deviation from traditional Shakespearean staging. The film rejects opulent sets in favor of location shooting in Spain—specifically the sun-drenched warehouses and cobbled alleys of Valencia and Barcelona—imbuing Verona with an earthy realism. The result is a city that feels lived-in, crowded, and politically charged. Cinematographer Robert Krasker employed high-contrast shadows to mirror the feud’s darkness, with flickering candlelight and harsh midday sun underscoring pivotal scenes. The courtroom sequence, shot in tight, claustrophobic frames, amplifies legal injustice and the impossibility of resolution. Reed’s direction treats Shakespeare not as an abstract text but as a living, breathing human drama—one defined by gesture, silence, and confrontation rather than poetic soliloquy alone. In Reed and co-writer Richard Hughes’ adaptation, the film honors Shakespeare’s language while streamlining verbosity to increase dramatic momentum. Iambic pentameter is preserved, but lines are delivered with naturalistic pacing, allowing emotional weight to emerge from pause and inflection rather than rhetorical flourish. A pivotal example is the balcony scene: instead of long-winded declarations, Romeo’s “But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?” is undercut by breathy hesitation, making Juliet’s “Romeo, whoever thou art stand,” feel immediate and personal. The film’s use of silence—lingering stares, shared glances, unspoken promises—heightens tension far more than words. As literary critic Claudia Gold notes, “The 1968 version lets the silence *amen* the tragedy—Shakespeare’s genius given breath through cinematic stillness.” Released in 1968—a year of global upheaval—*Romeo and Juliet* resonated beyond its narrative, reflecting societal unrest through the Prcons暿 turbines of class division, youth rebellion, and familial erosion. The film’s gritty realism mirrored Post-War disillusionment, rejecting romantic escapism in favor of raw authenticity. Brando’s Romeo, an outsider caught between love and doctrine, echoed the alienated youth of the 1960s grappling with tradition and modernity. Moreover, the casting of mixed-heritage actors (notably Anthony Quinn as Mercutio) introduced a subtle multiculturalism, softening Shakespeare’s Italian specificity into a more universal tragedy. The film’s visual economy—tight framing, natural lighting, minimal set dressing—aligned with emerging European art cinema trends, distinguishing it from Hollywood’s grandiose adaptations. Romeo and Juliet (1968) remains a benchmark for Shakespearean cinema, influencing later filmmakers with its blend of fidelity and innovation. Its restrained aesthetic paved the way for adaptations like Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 version, which embraced theatrical spectacle with greater resources, but Reed’s film remains the gold standard for psychological realism. The film’s emphasis on performance—particularly Brando’s intimate interpretation—inspired a wave of actor-centered Shakespeare on screen. Beyond technique, it reignited public interest, introducing Shakespeare to younger, secular audiences through a contemporary lens. Decades later, its modes of storytelling endure in how literature is adapted: intimate character study over spectacle, psychological depth over vocal display.Casting the tragic stars: Brando, Olivier, and the human face of Shakespeare

Direction and visual storytelling: A Neorealist Verona

The power of silence and subtext in Shakespeare’s dialogue

Cinematic innovation and cultural context

Legacy: How the 1968 film shaped Shakespeare for new generations

In shaping cinematic memory, Romeo and Juliet 1968 proves that Shakespeare’s words require no era—only truth.

Related Post

Romeo and Juliet (1968): A Timeless Classic That Defies Time

Inm in the Spotlight: Redefining Digital Innovation Through Inception and Integration

Marital Status Revealed: Amberley Snyder’s Bold Unveiling of Personal Truth

Unlocking Excellence: A Deep Dive into USC Majors and University-Level Programs