Scientific Definition of Characteristic: The Empirical Core Behind Definition and Application

Scientific Definition of Characteristic: The Empirical Core Behind Definition and Application

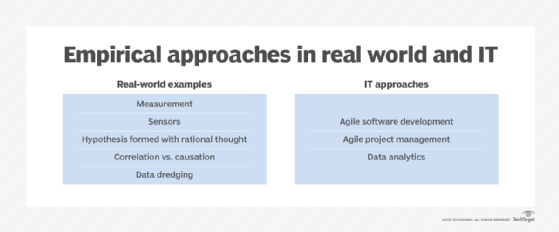

At its core, the scientific definition of a characteristic is a measurable, repeatable property or feature of a physical, chemical, or biological entity—essential for classification, identification, and prediction within scientific inquiry. This precise term anchors disciplines ranging from chemistry and biology to engineering and data science, providing a rigorous foundation upon which hypotheses are tested and observations interpreted. Far more than a mere descriptor, a characteristic embodies both observable behavior and quantifiable parameters that enable objective analysis and cross-validation across experimental settings.

In scientific terms, a characteristic is defined as “a quantifiable attribute or property of a system or substance that can be reliably measured and compared under controlled conditions” (ISO 13363-1:2021, Standard Metrology Principles). This definition emphasizes three key elements: measurability, repeatability, and relevance. Unlike subjective labels, a scientific characteristic must yield consistent data across multiple trials and contexts.

For instance, while “color” might appear to be a characteristic, its scientific utility arises only when defined via precise wavelength measurements in the visible spectrum or standardized visual assessment scales. Characters function as the building blocks of scientific models, underpinning everything from elemental tables to genetic markers. In chemistry, atomic radius—defined as the average distance between a nucleus and the electron cloud—is a fundamental physical characteristic used to predict reactivity and bonding patterns.

Similarly, in biology, the thermal tolerance range of a species represents a critical physiological characteristic, often determined through controlled stress experiments. “A characteristic thus serves as both a diagnostic marker and a predictive variable,” notes Dr. Elena Rossi, a biophysicist at the Max Planck Institute, “enabling researchers to infer function, health, or evolutionary adaptation from measurable traits.” Types of characteristics vary widely based on domain and methodology: - Physical characteristics include density, surface tension, refractive index, and electrical conductivity—properties typically assessed through standardized instrumentation.

- Chemical characteristics encompass acid-base pH, redox potential, solubility, and reaction kinetics. - Biological characteristics span metabolic rate, genetic expression profiles, morphological traits, and behavioral responses. - In data science, characteristics—or features—are extracted variables transformed from raw data to inform machine learning models, such as customer purchase frequency or soil moisture levels in environmental monitoring.

Measurement precision is paramount; uncertainty margins, calibration standards, and reproducibility protocols ensure scientific credibility. For example, the characterization of a superconducting material’s critical temperature (the temperature below which electrical resistance vanishes) demands cryogenic testing within ±0.001 K accuracy to support valid comparisons across labs. Such rigor transforms qualitative observations into quantifiable science, enabling technologies from semiconductor fabrication to climate modeling.

The scientific definition of characteristic also emphasizes its role in classification and inference. By identifying shared or divergent traits across populations, scientists define taxonomic groups—such as bacterial species distinguished by 16S rRNA gene sequences—or classify materials into phases based on phase diagrams. “Characteristics aren’t static descriptors; they are dynamic indicators of underlying systems,” explains Dr.

Marcus Lin, a materials scientist at MIT, “they reveal interactions at scales from quantum to ecosystem.” Historically, the formalization of characteristics evolved from early empiricism toward standardized methodologies. The advent of spectroscopy in the 19th century, for instance, enabled precise chemical characterization by analyzing light absorption patterns, revolutionizing analytical chemistry. Today, techniques like X-ray diffraction, mass spectrometry, and genomic sequencing provide unprecedented resolution, expanding how characteristics are identified and leveraged across research.

In practical application, characteristics form the backbone of diagnostics, quality control, and innovation. Medical tests evaluate biomarkers—such as blood glucose levels or tumor markers—as clinical characteristics to detect disease. Industrial processes maintain standards by monitoring parameters like viscosity or particle size distribution to ensure product consistency.

“Every engineered system, from a smart thermostat to a pharmaceutical drug, relies on carefully defined characteristics,” says Dr. Lin, “to ensure performance, safety, and scalability.” Ultimately, the scientific definition of characteristic represents more than a formal definition—it embodies a discipline’s commitment to evidence, precision, and shared understanding. By reducing complexity to measurable, comparable traits, science advances from speculation to verification.

Characteristics bridge observation and explanation, inference and action, making them indispensable across natural and applied sciences. As research tools grow increasingly sophisticated, so too does the depth and utility of what defines a characteristic—rigorous, reproducible, and fundamentally essential.

Core Attributes Defining a Scientific Characteristic

A true scientific characteristic adheres to three interdependent criteria: objectivity, quantifiability, and contextual relevance.Objectivity ensures that measurements are free from subjective bias, relying on standardized instruments and protocols. Punctuality governs that values change predictably under defined conditions—measured with low uncertainty across repeated trials. Relevance ties the characteristic to a specific scientific question, ensuring its utility in testing hypotheses or guiding interventions.

> “Without objectivity, a characteristic risks becoming a reflection of the observer rather than the observed,” observes Dr. Rossi. “Quantification removes ambiguity; repetition confirms reliability.” Together, these principles transform discrete observations into robust scientific data.

Beyond these pillars, characteristics must be reproducible—independent researchers obtaining consistent results under identical conditions. This reproducibility validates findings against the cornerstone of the scientific method: peer repetition. For example, the specific heat capacity of pure gold remains invariant across multiple labs when measured within ±0.005 J/g·K, enabling reliable incorporation into thermal engineering models.

Moreover, a characteristic must possess discriminative power—the ability to distinguish meaningful differences between pairs or groups. In diagnostic testing, a blood pressure reading above 120/80 mmHg qualifies as clinically significant; in ecological monitoring, a soil pH below 5.5 signals acidity requiring remediation. This discriminative capacity enables classification, risk assessment, and decision-making grounded in empirical evidence.

Characteristics also exhibit scale dependence. The thermal conductivity of copper, for instance, varies with temperature and measurement range, requiring context-specific characterization. Similarly, gene expression levels measured via RNA sequencing reflect dynamic cellular states, necessitating controlled conditions to extract meaningful biological insights.

Importantly, characteristics evolve with technological advances. Traditional light microscopy characterized cell morphology largely by shape and size; modern super-resolution microscopy now captures subcellular protein dynamics and molecular interactions, enriching the functional interpretation of structural traits. This progression underscores how scientific understanding deepens as measurement capabilities expand.

In data-driven domains like machine learning, characteristics undergo transformation from raw features into engineered predictors. Feature selection methodologies identify which variables—temperature, humidity, transaction history—most strongly correlate with target outcomes, enhancing model accuracy and interpretability. Ultimately, a well-defined characteristic serves as a bridge between observation and theory, enabling both descriptive analysis and predictive modeling.

Its precision enables reproducible science and跨领域 applications—from drug discovery to climate modeling—demonstrating how a rigorous scientific definition drives innovation and discovery.

Physical vs. Biological Characteristics: Divergent Dimensions in Measurement

Physical and biological characteristics represent two distinct yet interrelated categories in scientific characterization, each defined by unique measurement criteria and applications.

Physical characteristics are concrete, often instrumental properties tied to tangible interactions—measurable through direct instrumentation such as force, temperature, or electromagnetic response. For example, melting point, electrical resistivity, and refractive index serve as foundational physical traits used across physics, chemistry, and materials science to classify substances and validate theoretical models. These attributes are generally invariant under stable environmental conditions and offer high reproducibility across laboratories, making them ideal for precision engineering and quality control.

Biological characteristics, in contrast, reflect dynamic, often complex traits rooted in living systems.

They include metabolic rates, genetic expression patterns, cell morphology, and behavioral responses—qualities that integrate internal regulation, external stimuli, and evolutionary adaptation. Unlike static physical measures, biological traits exhibit higher variability, influenced by genetic makeup, environmental conditions, and developmental stage, necessitating repeated sampling and statistical analysis to establish meaningful baselines. For instance, measuring EEG patterns during cognitive tasks reveals neural correlates of decision-making, yet subtle biases from task intensity or subject fatigue demand careful experimental control.

While physical attributes anchor objective verification, biological characteristics probe functional complexity, linking molecular mechanisms to organismal behavior and ecosystem dynamics. Bridging these domains, researchers increasingly combine biosensors and computational modeling to decode how physical inputs translate into biological responses, advancing personalized medicine, ecological forecasting, and synthetic biology. This synthesis underscores that both characteristic types are indispensable—physical for accuracy, biological for insight—forming a cohesive framework for understanding life and matter alike.

Developing Reliable Characterization Protocols: Standards and Best Practices

Constructing a scientifically valid characteristic requires a robust methodology grounded in standardization, calibration, and reproducibility.The process begins with defining clear operational criteria: what constitutes measurement, under what conditions, and using which instruments. Without explicit protocols, results risk inconsistency, undermining peer acceptance and practical utility.

Core steps in developing a reliable characteristic include: - **Definition Clarity:** Articulate the characteristic in measurable, operational terms—e.g., “heart rate variability measured via ECG over 5-minute intervals during rest and stress.” - **Instrumentation Calibration:** Ensure devices conform to national or international standards (e.g., ISO, NIST) through traceable references. - **Control of Variables:** Identify confounding factors (temperature, humidity, biological state) and standardize their conditions.

- **Sample Validation:** Confirm functionality through independent trials and inter-laboratory comparisons. - **Statistical Analysis:** Apply robust methods—mean, standard deviation, confidence intervals—to quantify uncertainty and validate significance. Regulatory bodies such as the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) provide comprehensive guidelines to ensure characterization quality.

For instance, WHO protocols for diagnosing infectious diseases mandate standardized nucleic acid amplification test parameters, minimizing false negatives and ensuring global comparability.

Real-world application exemplifies this rigor. In semiconductor manufacturing, transistor threshold voltage is characterized under vacuum, room temperature, and specified biasing to ensure device reliability. Similarly, climate scientists characterize global precipitation patterns using globally coordinated rain gauge networks and satellite data fusion, reconciling regional disparities for accurate modeling.

These practices exemplify how methodological discipline transforms ambiguous observations into actionable, universally recognized metrics. Ultimately, a well-developed characteristic protocol bridges discipline-specific needs with universal scientific standards. It safeguards against bias, enhances reproducibility, and enables cross-context validation—cornerstones of trustworthy scientific progress.

Related Post

Josh Allen News and Charlie Kirk’s Unexpected Link: Inside the GOP Nexus

Redbox and New Releases: Your Ultimate Guide to Blockbuster Rentals at Your Doorstep

How Old Is Megan Fox? Unveiling the Age of the Pop Culture Star

Maritess Revilla and Iking Araneta: A Dynamic Duo Shaping Philippine Politics and Media