Siderotic Granules with Prussian Blue: Unlocking the Science Behind a Rare Iron Deposition Disorder

Siderotic Granules with Prussian Blue: Unlocking the Science Behind a Rare Iron Deposition Disorder

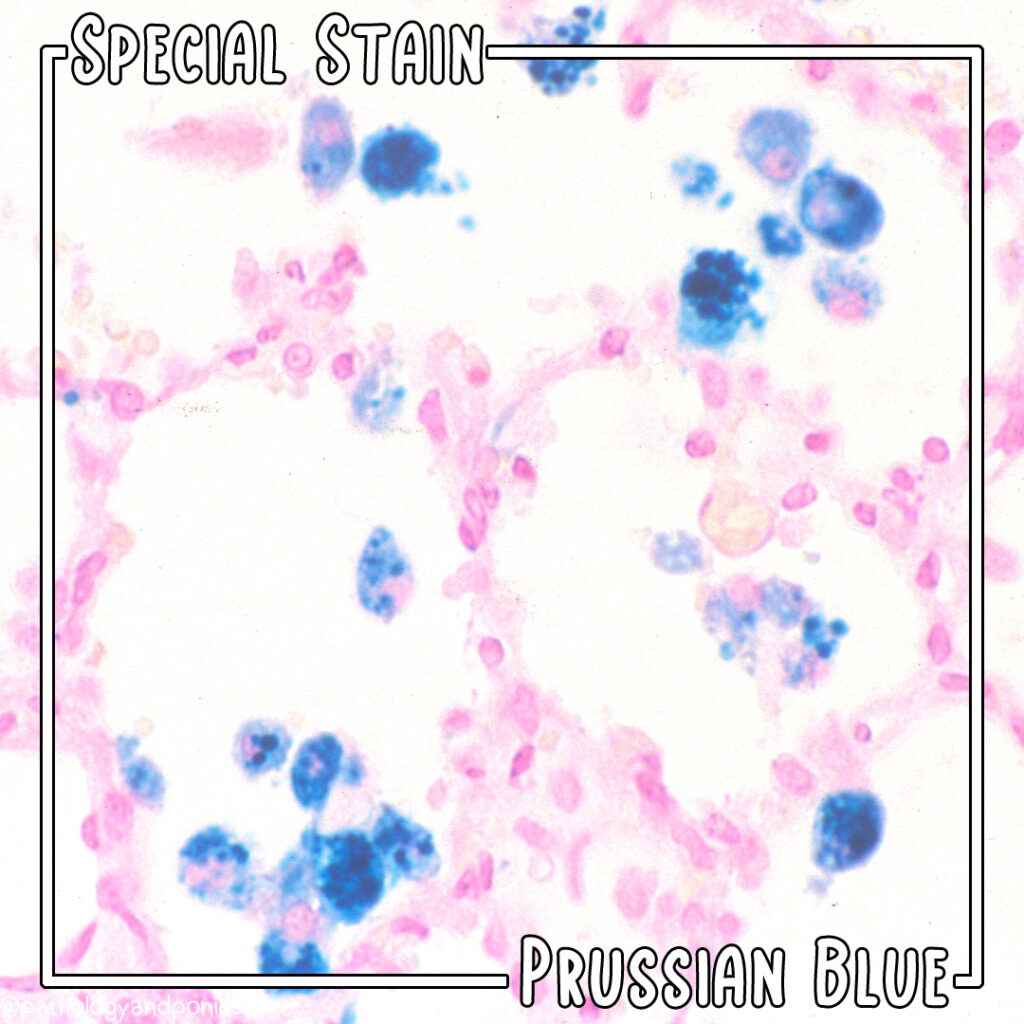

When siderotic granules—microscopic iron-containing deposits—appear in unexpected cellular contexts, diagnostic clarity becomes critical. Among the most intriguing and clinically significant examples is the presence of siderotic granules exhibiting characteristic Prussian Blue staining, a hallmark that guides precise identification and understanding. These granules, composed primarily of ferric iron automatsonically stored within lysosomal compartments, serve as both diagnostic markers and windows into pathological iron metabolism.

Their detection, especially with Prussian Blue, offers invaluable insight into conditions where iron accumulation disrupts normal tissue function.

What Are Siderotic Granules and How Do They Form?

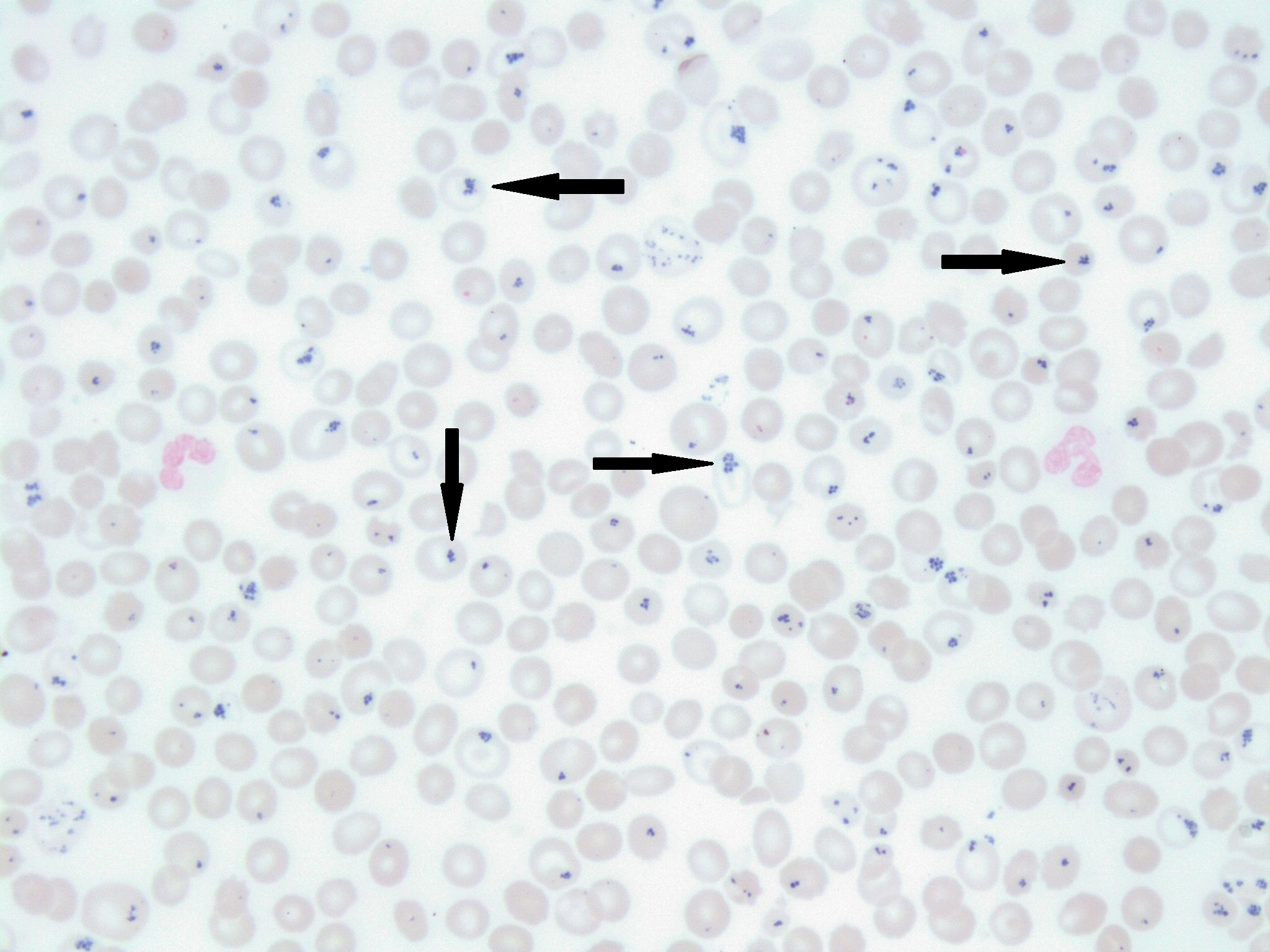

Siderotic granules are specialized intracellular inclusions found predominantly in hepatocytes, hepatobiliary cells, and occasionally neurons, where they represent a controlled sequestration of iron. They form when excess iron is internalized and bound to ferritin or periplasmic matrix proteins, accumulating in lysosomes that stain deeply with Prussian Blue due to the ferric ions’ high affinity for ferrocyanide.This reaction—developing a characteristic Prussian blue color—losses no ambiguity in confirming iron-laden granules. Unlike general iron deposits, siderotic granules indicate active but regulated iron storage, distinct from the more dangerous forms of iron overload seen in hemochromatosis or chronic transfusion-related iron deposition. <> • **Composition**: Primarily ferrihydrite, a poorly crystalline iron oxide-hydroxide, embedded in a protein-rich granule matrix.

• **Location**: Frequently observed in liver cells, bile duct epithelia, and neurons in rare neurodegenerative or metabolic disorders. • **Staining Behavior**: Prussian Blue produces intense blue coloration even at low iron concentrations, enabling reliable visualization under standard histological microscopy.

Prussian Blue Staining: The Gold Standard for Confirming Iron Deposition

Prussian Blue, chemically known as ferric ferrocyanide (Fe₄[Fe(CN)₆]₃), is more than a laboratory dye—it is a diagnostic pillars-through-history tool in iron pathobiology.When applied to tissue sections staining siderotic granules, Prussian Blue reacts with free ferric ions (Fe³⁺) present in iron deposits, producing intense, uniform blue precipitation. This color change is unmistakable: well-defined granular or crystalline patterns within cells confirm not just iron presence, but specific iron-bound structures. Unlike histochemical stains prone to variability, Prussian Blue delivers high specificity and reproducibility.

Its ability to highlight granular iron preserves critical spatial and morphological data, allowing experts to distinguish true siderotic granules from artifact or other pigment inclusions. In clinical practice, it serves as a rapid, objective method—essential in pathology labs where timely diagnosis can alter treatment pathways. <> - **Mechanism**: Iron (Fe³⁺) binds to ferrocyanide ligands within Prussian Blue crystals, precipitating as intense blue complexes.

- **Microscopic Clarity**: Even minute iron deposits reveal themselves with high contrast against tissue background. - **Clinical Utility**: Confirms iron-laden granules in liver biopsies, bile duct samples, and neurological tissues.

Clinical Significance and Associated Disorders

The presence of Prussian Blue-positive siderotic granules correlates with specific clinical scenarios where iron homeostasis is perturbed.While not synonymous with disease per se, their detection guides clinicians toward deeper investigation of underlying metabolic or genetic causes. Notable contexts include: - **Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Iron Overload (PF/HFIO)**: A rare autosomal recessive disorder where defective iron export from hepatocytes leads to intracellular accumulation. Siderotic granules with Prussian Blue staining serve as a key histologic discriminator from other hepatic iron disorders.

- **Neurodegenerative Diseases**: Iron deposition in brain regions such as the basal ganglia—seen in conditions like neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA)—can exhibit Prussian Blue–stained granules, suggesting lysosomal iron burden as a contributing factor. - **Metabolic Dysregulation Syndromes**: Conditions like Down syndrome or certain mitochondrial disorders sometimes present with atypical iron storage patterns, where consistent staining helps differentiate secondary iron changes. Importantly, Prussian Blue staining does not distinguish between benign sequestration and pathologic overload—it flags areas for further molecular and functional analysis, such as ferritin mutation screening or iron turnover studies.

<> - **Diagnostic Clue, Not Diagnosis**: Staining confirms iron presence but requires integration with clinical, biochemical, and genetic data. - **Differential Utility**: Distinguishes siderotic granules from melanin, lipofuscin, or other pigments seen under routine stains. - **Prognostic Insight**: While granules may indicate iron accumulation, severity correlates with tissue-specific damage—liver failure or neurodegeneration depends on deposition pattern and volume.

Limitations and Technical Considerations

Despite its robustness, Prussian Blue staining carries caveats. False positives can occur if tissues are improperly fixed—dehydration errors may cause incomplete iron release or uneven staining. Moreover, Prussian Blue highlights iron in granules rather than dissolved iron in cytoplasm, meaning some labile iron may be missed.Interpretation demands expertise to avoid overdiagnosis. Emerging adjunctive techniques—such as quantitative labile iron probe imaging and electron microscopy combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy—complement Prussian Blue by offering elemental precision. Yet, Prussian Blue remains irreplaceable due to its accessibility, speed, and established role across pathology settings.

<> - **Fixation Protocol**: Fresh or aldehyde-fixed tissues better preserve labile iron; formalin over dehydration may reduce staining clarity. - **Stain Variability**: Inter-lab consistency varies; standardized protocols enhance reliability. - **Complementary Tools**: Best used alongside histopathology, serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, and genetic testing.

The Future of Prussian Blue in Iron-Related Pathology

Prussian blue staining of siderotic granules stands as both a diagnostic anchor and a research gateway in the study of iron metabolism. Its enduring relevance lies not only in confirming iron deposits but in enabling targeted investigations into disease mechanisms. As precision medicine expands, tools like Prussian blue serve as critical links—bridging morphology, chemistry, and clinical care.For clinicians and researchers alike, understanding these granules enhances the ability to detect, classify, and manage conditions rooted in iron dysregulation, offering hope for more accurate, individualized treatments. In an era where iron is increasingly recognized as a double-edged sword—vital yet potentially toxic—Prussian blue remains an indispensable sentinel, revealing hidden deposits and guiding the path toward timely, informed intervention.

Related Post

Unlock Seamless Xfinity Email Sign-In: Your Quick Guide to Secure, Simple Access

Pseithosese’s Happy Years 2013 Sub Indo: How Nonton Filmnya! Reignited a Golden Era of Film Culture

Behind the Smoke and Mirrors: The Human Faces That Breathed Life into Mad Men’s Iconic Characters

Where To Watch Shameless Us Streaming Options And More