Single Replacement: The Chemical Swap That Powers Innovation

Single Replacement: The Chemical Swap That Powers Innovation

Behind every synthetic battery, purified metal catalyst, or purified solvent lies a deceptively simple yet powerful transformation: single replacement in chemistry. This fundamental reaction—where one element displaces another in a compound—fuels numerous technological advancements and industrial processes. Defined precisely as the chemical exchange where an atom or ion in a compound is substituted by another of higher reactivity, single replacement underpins modern materials science, pharmaceuticals, and environmental solutions.

From gold catalyzing hydrogen production to silver ions neutralizing bacterial membranes, this reaction is not just academic—it’s a real-world workhorse of innovation.

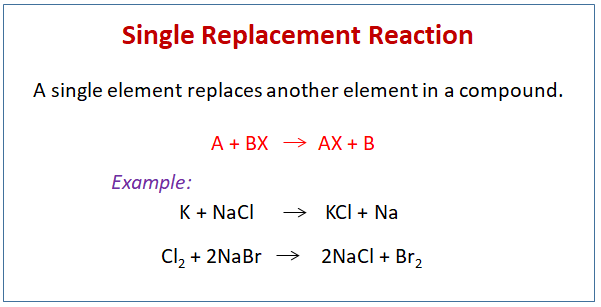

At its core, a single replacement (or single displacement) reaction follows the general form: A + BC → AC + B, where element A replaces element B in a compound BC. This process thrives under conditions of relative reactivity: a more reactive metal can displace a less reactive one from a compound.

For example, zinc powder readily displaces copper from copper sulfate solution, producing metallic zinc and copper sulfate. With the simplicity and predictability of the process, single replacement stands out among displacement types—silver more easily displacing mercury from its salts, or magnesium overcoming aluminum in certain electrolytic setups—all governed by the reactivity series, a cornerstone of understanding these transformations.

The Mechanics of Atomic Substitution: What Drives a Single Replacement Reaction?

Single replacement is fundamentally driven by differences in elements’ natures—specifically their positions in reactivity rankings.Metals, for instance, tend to lie on the left of the reactivity series, characterized by high electron-loss propensity. Groups 1 and 2 elements like sodium, potassium, and magnesium are prime candidates. When placed in contact with compounds containing less reactive metals—such as iron(III) chloride or copper sulfate—principle governs the exchange.

Reactivity Series & Displacement Potential The reactivity series serves as the golden rule: the more reactive metal displaces the less reactive one. This hierarchy arises because lower-reactivity metals have a stronger thermodynamic drive to lose electrons, making them effective replacements. For example, zinc’s strong affinity for electrons allows it to displace copper—where zinc’s electron-donating tendency overcomes copper’s resistance.

In aqueous solutions, chlorine is far less reactive than sulfur and displaces it from sulfides or chlorides. Another critical factor is compound stability. Displacement succeeds when the product compound is more stable than the reactants.

For instance, iron displaces copper from copper sulfate not because copper is less reactive (iron is), but because the resulting iron-copper alloy is far more stable energetically. Similarly, in hydrogen electrodes, hydrogen’s displacement of metals like gold or platinum in electrochemical cells stems from its ability to form stable, lower-energy bonds. The equilibrium of these reactions depends on Gibbs free energy change (ΔG).

Only when the reaction yields a negative ΔG—meaning energy is released and the products are thermodynamically favored—does the displacement proceed as a spontaneous single replacement. This intrinsic energy calculus defines whether substitution leads to observable change.

Beyond fixed pairs like zinc and copper, thousands of replacements operate daily in laboratories and factories.

In metal extraction, for example, aluminum has long displaced iron from iron ore in high-temperature electrolytes due to its exceptional reactivity. Though rare in raw ores, such reactions become viable under industrially controlled conditions. Other vital examples include: - Sodium vaporizing copper from copper sulfate solution - Silver ions replacing mercury in non-aqueous electroplating baths - Zinc replacing lead in minimizing corrosion of steel (galvanization) Each case reflects how elemental hierarchy and environmental control—temperature, concentration, solvent—collaborate to drive substitution efficiently.

Applications That Shape Industries and Daily Life

Single replacement reactions are not mere laboratory curiosities—they are foundational to multiple sectors, enabling breakthroughs that touch nearly every corner of modern existence.Metal Extraction and Refining

Though naturally occurring ores often resist spontaneous displacement, industrial processes exploit controlled single replacements. Aluminum, extracted from alumina via electrolysis, still benefits from displacement: newly reactive aluminum displaces iron from molten electroresidues, refining output.Zinc galvanization—where dipping steel into molten zinc relies on zinc’s reactivity to displace less reactive iron ions in the bath, creating a self-healing protective layer—prevents rust and extends life spans of infrastructure, vehicles, and appliances.

Electrochemistry and Energy Conversion

In batteries and electrolysis, displacement reactions are the engines of charge transfer. Zinc-manganese dioxide cells, common in disposable batteries, depend on zinc’s strong reducing power: zinc atoms release electrons to displace Mn²⁺ ions, generating current.Similarly, hydrogen electrodes exploit single replacement—hydrogen ions are reduced to molecular hydrogen while displacing inert electrode metals—critical in fuel cells and green hydrogen production. These systems hinge on precise control of reactivity and environment.

Pharmaceuticals and Material Science

Even drug development relies on substitution.Replacing functional groups in molecular scaffolds can alter solubility, bioavailability, and reactivity. In catalysis, single replacement guides the design of novel materials. For instance, mercury cadmium telluride at the surface can be “tuned” by displacing surface atoms, adjusting optical properties for infrared detectors.

Advances in nanomaterials often begin with controlled replacement at atomic interfaces, enabling tailored reactivity and performance.

Environmental Remediation

Iron nanoparticles deployed to clean contaminated soil or water rely on engineered displacement. Made highly reactive, they displace toxic metals like hexavalent chromium (Cr⁶⁺) by reducing and immobilizing them into less hazardous Cr³⁺.In such restorations, single replacement acts as nature’s cleanup crew, transforming hazardous ions into stable, inert forms—proving chemistry’s power to heal.

Each application underscores a deeper truth: single replacement is more than a textbook definition. It is a dynamic, predictable mechanism embedded in the tools that build progress—from the smartphones in our pockets to the medical devices saving lives.

Controlled, selective, and scalable, this reaction remains chemistry’s silent architect of transformation.

Related Post

Lincoln County, NV: Where High Desert Secret Meets Rocky Legacy

Mastering Recoil: The Best 5/8x24 Muzzle Brake for .44 Magnum

Chanda Rubin’s Rising Net Worth: A Case Study in Strategic Wealth Building and Exceptional Earnings

Vn Index: The Essential Compass for Navigating Vietnam’s Complex Media and Data Landscape