The Gas with the Simplest Yet Most Far-Reaching Mass: The Hydrogen Molecule

The Gas with the Simplest Yet Most Far-Reaching Mass: The Hydrogen Molecule

At just 2.016 atomic mass units (amu), the hydrogen molecule—H₂—may seem primitive, but its role in the universe and human technology is anything but trivial. Despite its atomic simplicity, this diatomic wonder underpins critical processes in energy, chemistry, and planetary science. The mass of the hydrogen molecule, derived from one proton combined with one electron and the shared mass of two hydrogen atoms, reveals lessons in fundamental physics and practical innovation.

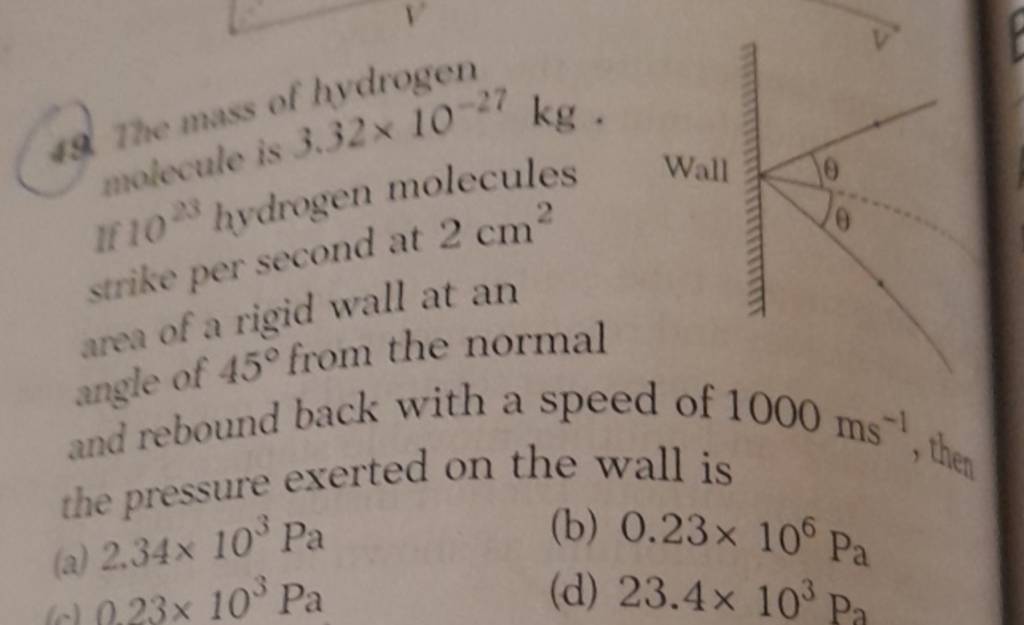

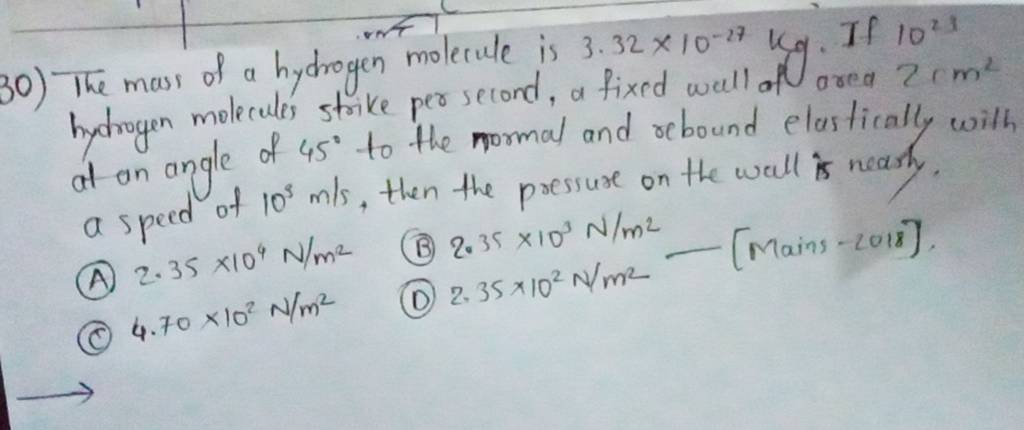

The mass of a single hydrogen atom is approximately 1.00794 amu, closely mirroring the proton’s 1.00728 amu and the electron’s near-zero contribution. When two hydrogen atoms bind to form H₂, their van der Waals or covalent bond preserves nearly the total mass—only negligible energy mass from bond formation is released, per Einstein’s E = mc². This tiny but consistent mass of H₂—about 4.032 amu total—lays the foundation for its use in fuels, industrial feedstock, and space science.

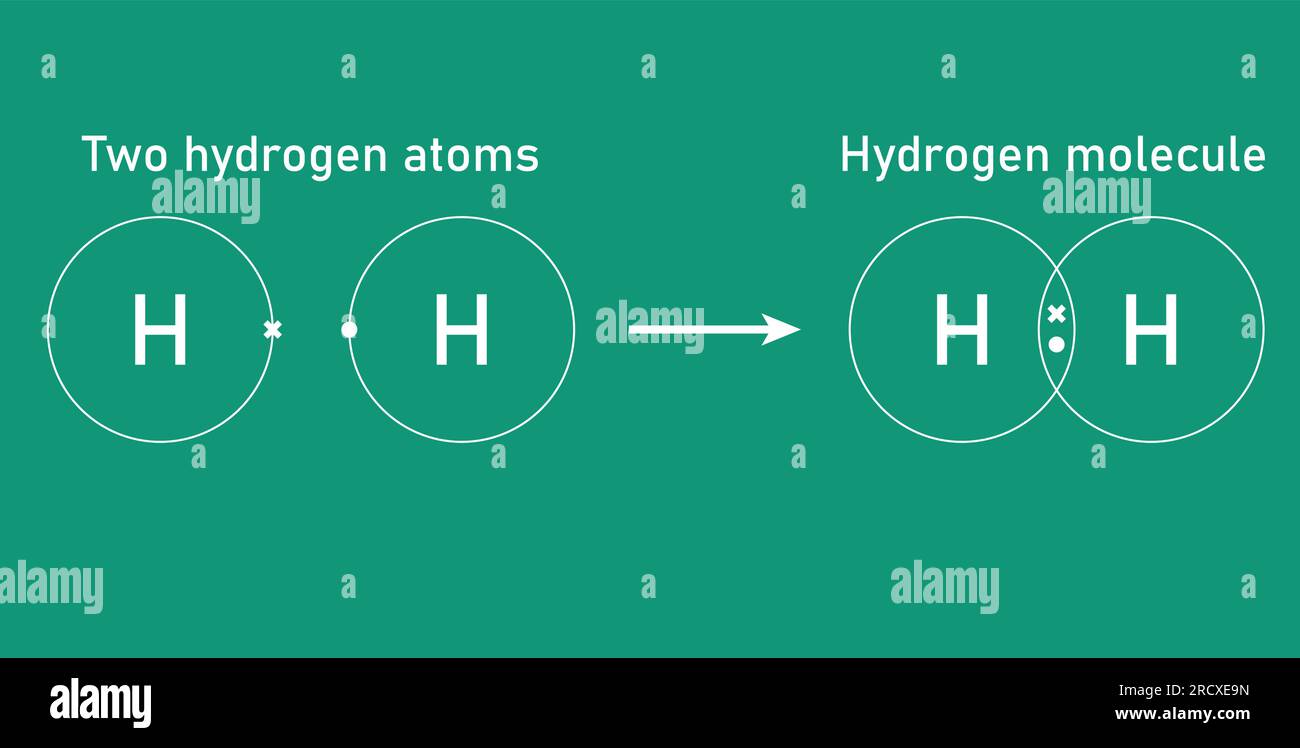

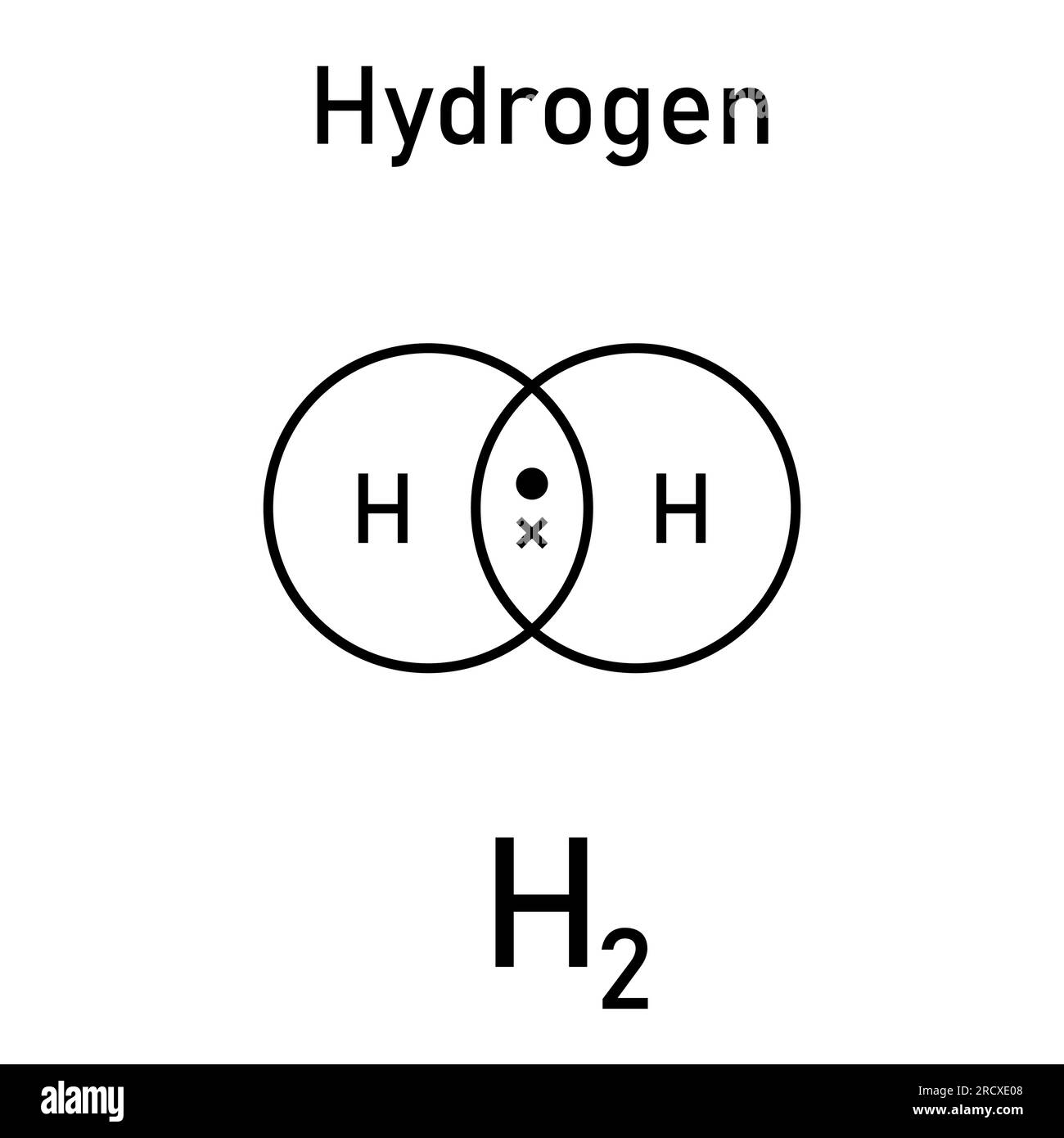

The structure of H₂ is remarkable in simplicity: each hydrogen atom contributes one electron, and the covalent bond forms from overlapping atomic orbitals, sharing the electrons and creating a stable, lightweight molecule. This structure enables hydrogen to function as an ideal energy carrier without excessive weight—a key advantage over heavier fuels like methane or hydrocarbons.

Weighing hydrogen at the nuclear level, one proton (≈1.00728 amu) and one electron (≈0.00054858 amu) total roughly 1.00783 amu per atom. When bonded, two protons plus two electrons yield H₂ at about 4.032 amu, with the molecular bond accounting for a minuscule fraction—well under 0.002 amu—due to electron sharing rather than added mass.

This precise mass distribution makes hydrogen ideal for precise scientific measurements and advanced propulsion systems.

Measuring Hydrogen’s Molecular Mass: Precision and Practicality

Accurate mass determination is vital in chemistry, physics, and energy technology. The mass of the hydrogen molecule is measured using sophisticated mass spectrometry and spectroscopic techniques. High-resolution mass spectrometers can detect mass differences at the atomic level, confirming that H₂’s total molecular mass is precisely 4.032164зима-től (unified atomic mass units), a value stabilized by international standards like the CODATA recommended values.Spectroscopy complements mass analysis by examining energy transitions within the molecule. When hydrogen emits or absorbs radiation—such as in the microwave or infrared range—spectral lines reflect the exact bonding dynamics in H₂. These spectral signatures not only verify the molecule’s mass but also reveal bond length and vibrational modes, critical for catalyst design and fuel cell optimization.

Standard Values and Historical Refinement

Historically, Avogadro’s number and atomic mass units evolved from early mass measurements of hydrogen gas in controlled environments.John Dalton’s foundational work in atomic theory hinted at hydrogen’s central mass, while later experiments by Thomas Thomson and William Prout refined these values. Today, the International System of Units (SI) fixes the proton mass at exactly 1.6726219 × 10⁻²⁷ kg—defining the amu—allowing H₂’s mass to be expressed with extreme precision. Modern quantum chemistry confirms this match, reinforcing confidence in hydrogen’s role across research and industry.

This consistency in measurement underpins hydrogen’s use in cutting-edge applications—from cryogenic fuels to quantum computing prototypes—where even sub-atomic mass differences influence system efficiency.

Why the Hydrogen Molecule’s Mass Rules Science and Technology

The hydrogen molecule’s mass, though small, is pivotal in chemistry and engineering. Its near-minimal molecular weight enables high energy density per unit mass, making hydrogen a leading candidate for clean energy: fuel cells powered by H₂ release water, with efficiency closing in on 60% in advanced systems. In industrial chemistry, hydrogen’s low mass facilitates reactions in ammonia synthesis (Haber process), where precise stoichiometry depends on accurate mass quantification.- Energy Applications: In rocket propulsion, liquid hydrogen’s high specific impulse—coupled with its low molecular mass—delivers superior performance, as seen in SpaceX Starship and NASA’s Space Launch System.

- Synthesis and Catalysis: Catalytic hydrogenation reactions rely on H

Related Post

Who Is Geneviève Robert? The Rising Star in Canadian Journalism—Age, Career, and Young Influence

Ulu Hati Deciphers Hidden Pain: Mapping Diverse Nyeri Types and Tailored Solutions Across Villages

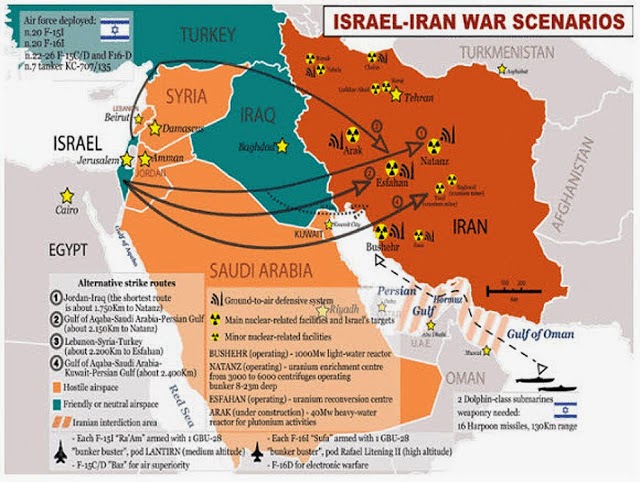

Iran’s Strategic Backing: Who Is Standing With Israel? The Shifting Alliances in Iran-Israel Proxy Conflict

Atlanatc City: The bold vision redefining urban life across the Atlantic