The Living Tapestry: How Ecological Community Definition Science Reveals Nature’s Interwoven Networks

The Living Tapestry: How Ecological Community Definition Science Reveals Nature’s Interwoven Networks

At the heart of ecology lies a foundational principle: ecosystems are far more than mere combinations of species, but dynamic, structured communities defined by their interactions, resilience, and shared environment. Ecological Community Definition Science offers a rigorous framework for understanding these intricate webs of life, where species coexist, compete, cooperate, and shape their habitats through persistent ecological relationships. This scientific approach moves beyond cataloging organisms to analyzing the functional, spatial, and temporal dimensions of community assembly—shedding light on biodiversity, stability, and ecosystem health in an era of rapid environmental change.

Defining an ecological community with scientific precision demands more than observing who lives where; it requires mapping the rules governing species interactions and environmental filters. According to the Society for Ecological Restoration, “an ecological community consists of functionally interdependent species occupying a defined space and exchanging energy, matter, and information.” This definition underscores that communities are not static inventories but living systems shaped by abiotic constraints—such as soil composition, climate, and topography—and biotic forces, including predation, competition, mutualism, and succession.

Core Components of Ecological Communities: Structure and Function

The structure of an ecological community is defined by four key components: species composition, functional diversity, spatial distribution, and trophic organization.- **Species Composition** refers to the specific mix of taxa present in a given area. This is the most visible aspect: a coral reef teems with fish, invertebrates, and algae, whereas a boreal forest is dominated by conifers and specialized mammals. Yet composition is not random.

“Species presence or absence reflects evolutionary history and environmental tolerances,” explains ecologist Dr. Elena Marquez. “Each species functions as a specific node in the community’s ecological network.” - **Functional Diversity** captures the range of roles organisms play—such as nitrogen fixers, pollinators, decomposers, or keystone predators.

High functional diversity enhances community resilience, ensuring that ecological roles persist even if certain species decline. For example, multiple pollinator species may fulfill similar functions, buffering against loss of any single group. - **Spatial Distribution** highlights how individuals and species are organized across landscapes—whether clustered, dispersed, or evenly spaced.

This reflects resource availability, dispersal abilities, and species interactions. Fragmented habitats often disrupt these patterns, reducing connectivity and increasing extinction risks. - **Trophic Organization** defines energy flow through food webs, from primary producers to apex consumers.

These hierarchical relationships establish energy pathways critical to population balance and nutrient cycling. Disruptions here—such as the decline of top predators—can trigger cascading effects across entire communities, a phenomenon well-documented in trophic cascade studies.

Community Dynamics: From Stability to Change

Ecological communities are not passive formations but dynamic entities constantly adapting to disturbance and environmental pressures.Stability—the ability to resist or recover from change—is a central metric in community definition science. Researchers assess stability through resistance (ability to absorb change) and resilience (capacity to return to equilibrium). These are influenced by both community size and interaction complexity.

Succession—both primary (on bare substrate) and secondary (after disturbance)—reveals community progression over time. Early successional stages are dominated by fast-growing, opportunistic species; over decades, these give way to slower-growing, competitive species better adapted to stable conditions. Classic studies, such as those by Henry Crosby Cowles on dune ecosystems, demonstrated how plant communities evolve with shifting soil and moisture, ultimately reaching a climax community in stable settings.

Yet modern ecological science recognizes communities as openly adaptive, not locked in irreversible states. “Communities reorganize continuously,” notes Dr. Rajiv Nair, a leading ecologist.

“Climate shifts, invasive species, and human activity drive rapid reassembly, often into novel configurations that challenge traditional equilibrium models.” < illustration of community dynamics in urban ecosystems - In urban parks, pigeons and rats may thrive due to human-provided resources, altering native species balance. - Green roofs support bog-inspired communities, showing adaptive capacity despite harsh conditions. - Fragmented forests see opportunistic species dominate, reducing biodiversity and long-term stability.

A critical concept in contemporary community definition science is **niche theory**, which explains species coexistence through resource partitioning and differential tolerances. When species occupy distinct niches—differing in diet, activity times, or habitat use—they minimize direct competition, enabling higher species richness. This niche-based structuring contrasts with neutral models, which assume random distribution, and highlights the deterministic nature of ecological communities.

Field studies across biomes reinforce these principles. In Amazonian rainforests, stratified communities of epiphytes, understory herbs, and canopy trees reflect layered resource use. In Arctic tundra, seasonal snowmelt triggers precise synchronies in plant emergence and insect emergence, revealing tight functional integration.

These examples demonstrate that ecological communities are finely balanced not by chance, but by evolved interactions. Understanding ecological communities through this scientific lens offers vital tools for conservation and land management. By identifying keystone species, mapping functional traits, and monitoring shifts in community structure, scientists and stewards can predict ecosystem responses and prioritize actions.

Rather than viewing communities as isolated snapshots, Ecological Community Definition Science positions them within broader ecological narratives—highlighting their fragility, complexity, and enduring capacity for adaptation. In a world facing unprecedented environmental transformation, the precision of ecological community science provides a compass. It reveals not just who lives where, but how relationships, diversity, and resilience sustain life’s vibrant interconnectedness—making this field indispensable to both knowledge and stewardship of Earth’s living systems.

The Future of Community Science: Integrating Data and Complexity

Advances in remote sensing, DNA metabarcoding, and computational modeling now allow ecologists to analyze communities at unprecedented scales and resolutions. Satellite imagery maps species distributions across continents, while soil and water DNA samples reveal hidden microbial and invertebrate communities once invisible to traditional surveys. Machine learning models interpret vast datasets, identifying patterns in species turnover, invasion dynamics, and climate-driven shifts.“This era of synthetic ecology,” says Dr. Nair, “merges field ecology, genomics, and big data to reconstruct communities holistically.” Such integration enables not only better understanding but proactive

Related Post

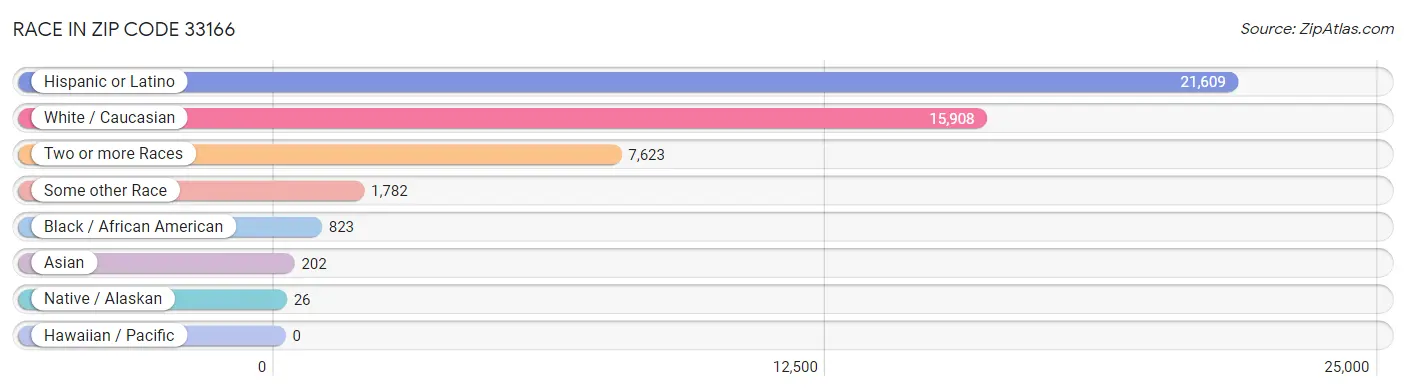

Miami Fl 33166: Your Exact Zip Code Breakdown That Reveals Where to Live, Work, and Thrive

Chick Fil A New York Serves Halal with Swift Precision

Where Is Nevada? A Deep Dive into America’s Enigmatic Silver Heartland

Decoding Hi: The Precision of Lewis Dot Structures in Visualizing Molecular Bonds