Trigonal Pyramidal vs. Trigonal Planar: The Atomic-Shaped Battle That Defines Molecular Geometry

Trigonal Pyramidal vs. Trigonal Planar: The Atomic-Shaped Battle That Defines Molecular Geometry

Molecules shape the world at the nanoscale, and among the most influential structural motifs are the trigonal pyramid and the trigonal planar geometries. These two distinct yet closely related arrangements—derived from VSEPR theory—dictate the spatial behavior of countless chemical compounds, from ammonia’s lone-paired electron cloud to the symmetrical precision of boron trifluoride. Understanding the subtle but critical differences between trigonal pyramidal and trigonal planar configurations is essential for chemistry students, researchers, and professionals alike, as these shapes directly influence reactivity, polarity, and intermolecular interactions.

The heart of the distinction lies not just in atomic arrangement, but in the presence (or absence) of lone electron pairs—transforming probability into physical reality.

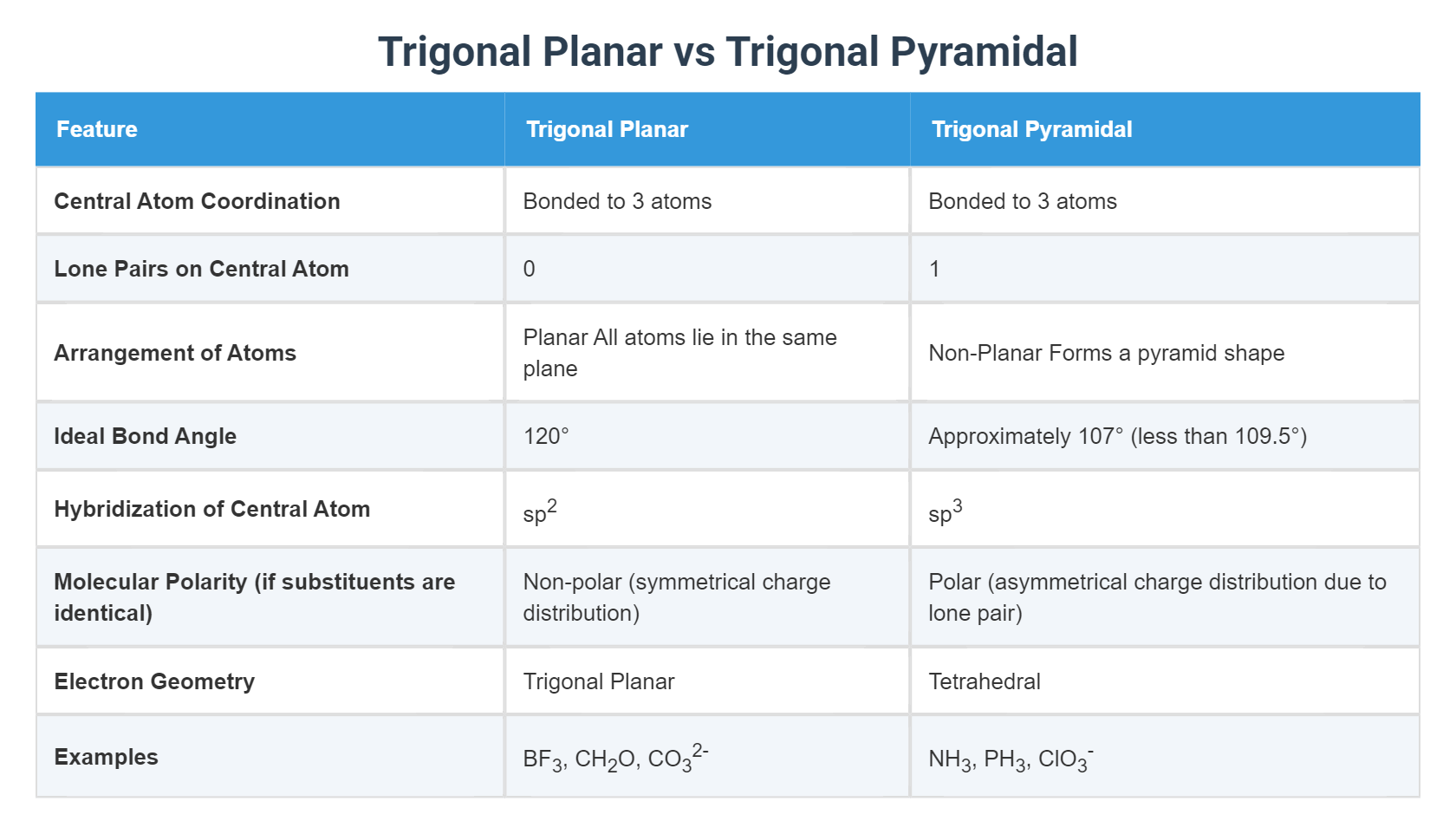

At the core of molecular geometry lies Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory, a model that explains how electron domains around a central atom arrange themselves to minimize repulsive forces. In a trigonal planar geometry, a central atom is surrounded by three bonding pairs and no lone electrons, forming a flat, equilateral triangular shape with bond angles of exactly 120 degrees.

Classic examples include boron trifluoride (BF₃) and sulfur trioxide (SO₃), where the central atom maintains ideal symmetry optimized by pure bonding. Conversely, the trigonal pyramidal shape arises when a central atom with three bonding pairs and one lone electron adopts a three-dimensional arrangement. The lone pair’s greater repulsive pull squishes the bonding orbitals closer together, resulting in a pyramidal configuration with bond angles compressed below 120 degrees—most notably in ammonia (NH₃), where the N–H–H angle measures approximately 107 degrees.

This structural shift underscores how electron configuration dictates geometry with remarkable precision.

The real-world implications of these shapes extend far beyond aesthetics—they govern chemical behavior in tangible ways. In trigonal planar molecules like BF₃, the symmetry furthers stability and symmetry-related reactivity; boron’s empty p orbital enables easy acceptance of electron pairs, making it a potent Lewis acid in catalysis and material science.

Meanwhile, trigonal pyramidal nitrogen in ammonia exhibits a distinctive trigonal dipole, enhancing solubility in water and enabling hydrogen bonding—a property central to biological systems. “The presence of the lone pair in trigonal pyramidal structures fundamentally alters molecular polarity,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a physical chemist at the Institute for Advanced Molecular Studies.

“This creates localized charge distributions that influence everything from solvation energy to enzyme-substrate interactions.” The contrast is not merely angular—it’s functional, shaping how molecules interact with solvents, catalysts, and other reagents.

Three key distinctions define these geometries beyond shape alone:

- **Electron Domain Count**: Trigonal planar involves three bonding pairs (and zero lone pairs) around the central atom; trigonal pyramidal features three bonding pairs plus one lone electron pair.

- **Bond Angles**: Planar geometry maintains ideal 120° angles, while the lone pair compresses adjacent bonding angles—often to under 110° in ammonia.

- **Reactivity and Polarity**: The lone pair in pyramidal structures induces asymmetry and enhanced polarity, increasing interactions like hydrogen bonding, whereas planar symmetry often yields net dipole cancellation in symmetric systems.

Real-world examples make these concepts concrete. Take BF₃: its planar form stabilizes reactive intermediates in organic synthesis and serves as a model Lewis acid. In contrast, NH₃’s pyramidal nature enables it to act as a protic solvent and biological ligand, leveraging its lone pair to form coordinate bonds with transition metals in enzyme active sites.

Another illustrative pairing is SO₃—trigonal planar and ideal for catalytic cycles in petrochemical refining—and PCl₃, where the trigonal pyramidal form influences its reactivity in nucleophilic substitution reactions.

Geometrical precision also shapes broader chemical principles. In coordination chemistry, the configuration around a central ion determines complex stability; octahedral complexes may adopt trigonal pyramidal distortions under ligand field effects, while trigonal planar transition states simplify reaction pathways in catalysis.

“The distinction between these geometries is not a minor nuance—it’s a foundational axis upon which molecular design turns,” emphasizes Dr. Rajiv Nair, a computational chemist specializing in structural chemistry. “Understanding when and why a molecule adopts one shape over the other opens doors to predicting—and designing—behavior at the atomic level.”

In applications ranging from pharmaceuticals to materials science, these structural motifs matter profoundly.

Trigonal pyramidal amines serve as proton acceptors in drug molecules, while trigonal planar carbonyl groups underpin the reactivity of carbonyl compounds, the backbone of organic synthesis. Catalysts often rely on precise electron domain control—using pyramidal Lewis acids like AlCl₃ in Friedel-Crafts reactions or planar transition-metal complexes in cross-coupling processes. In polymer chemistry, monomer geometry dictates chain formation, mechanical strength, and thermal stability.

For example, polymers with trigonal pyramidal units may exhibit enhanced intermolecular forces due to directional bonding from lone pairs.

The shift from trigonal planar to trigonal pyramidal is more than a pencil-and-paper rearrangement—it’s a quantum-level transformation that alters electron density, reactivity, and functional performance. Emphasizing electron pair dynamics reveals a deeper story: molecular geometry is not passive inertia, but an active determinant of chemical life.

From the reactivity of ammonia in atmospheric chemistry to the catalytic efficiency of boron-based compounds, this atomic-scale architecture shapes the molecular world we inhabit.

Ultimately, the trigonal pyramid and trigonal planar are not just shapes—they are blueprints etched in electron density, guiding how molecules behave, interact, and evolve. Mastery of these forms equips scientists with predictive power, turning abstract theory into practical insight.

In the ongoing quest to harness chemistry’s full potential, recognizing and applying these geometric principles remains both foundational and transformative.

![[Solved]: The molecular geometry around carbon B is trigon](https://media.cheggcdn.com/media/e9f/e9f2549f-40e8-4048-b9bb-9880641cc243/phpCkWlAg)

Related Post

Norah Jones: A Deep Dive into the Life and Legacy of a Voice That Defines Quiet Power

Matt Napolitano Flies Too Soon: Fox News Anchor and Reporter Dies at 33 After A Sudden End

How Many Fluid Ounces Make a Pound? The Definitive Guide to Fluid Ounces and Weight

Susan Lucci’s Unbelievable Journey: Remarkable Age, Timeless Icon, and the Secrets Behind a Hollywood Legend’s Longevity