Unearthing the Past: Old English Words That Define Modern Meaning Through Modern Synonyms

Unearthing the Past: Old English Words That Define Modern Meaning Through Modern Synonyms

The linguistic roots of English stretch far deeper than medieval manuscripts and hardy Anglo-Saxon settlers—many of its oldest words persist, not as relics, but as living elements woven into the fabric of modern expression. Among the most compelling connections lie in the fusion of Old English words and their contemporary synonyms: words whose ancient forms echo through centuries, revealing how meaning evolves while essence endures. By examining terms once inscribed in runic inscriptions and later recorded in Beowulf and the Anglian laws, one uncovers not only lexical continuity but a dynamic interplay of language, culture, and identity.

From the very foundation of expression, old vocabulary reveals unexpected relevance—proof that even words dormant in time often spark renewal today. The roots of English disproportionately draw from Germanic languages, with Old English forming the primary linguistic bedrock. Words such as *“good”* and *“bad”*—often assumed modern necessities—originate in Proto-Germanic *“*gut companions”* and *“*badil,”* respectively, reflecting a binary moral framework inseparable from early English worldview.

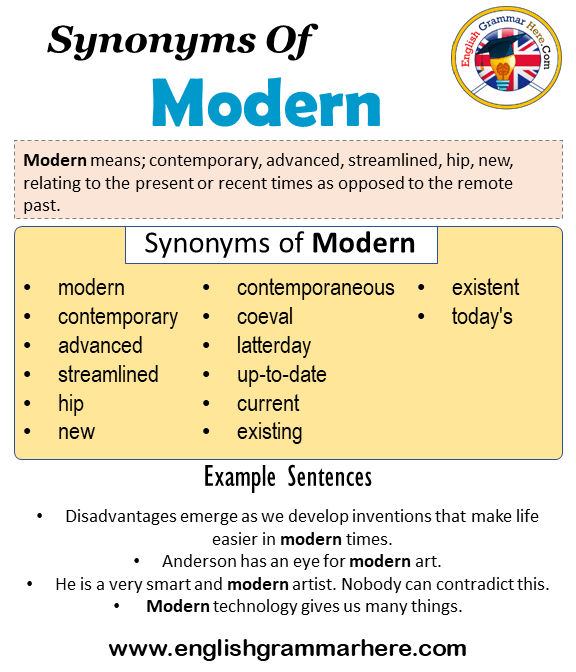

These basic terms persist not only in standard usage but as semantic anchors: “good,” for instance, retains deep philosophical weight, often synonymized in modern contexts not merely with “fine” or “correct,” but with *“positive”* or *“noble”*—capturing layers implied in the Old English *gōd*. Likewise, *“bad”* evolves into *“malicious”* or *“vile,”* each layer preserving a core of moral judgment distinct from mere factual descriptors. Here, synonym use in modern English finds fascinating parallels in Old forms.

Where contemporary usage might distinguish “happy” from “joyful,” the Old English *„heorot“* (from *heorth, “heart, fate”) designates not just joy but a deep, worded satisfaction—closer in meaning to *“contented”* or *“fulfilled.”* This nuance surfaces in synonym chains: *“glad”* (glæd) implies brightness of spirit, while *“merry”* (mearcus)—etymologically tied to *merran, “to make merry”*—speaks to cheerfulness born from shared celebration. Such distinctions highlight how Old English conceptions of emotion inform today’s subtle variations in emotional expression. Consider the Old English *„weard”*—a warrior’s oath, a pledged watch over a community or promise.

It is not merely “guard” or “watch” in modern dictionaries, but someone who embodies vigilance and moral responsibility. Synonyms like *“protector”* or *“sentinel”* capture part of its weight, yet none fully echo the ceremonial gravity embedded in *weard*. In modern legal or personal contexts, the term resonates in phrases like “sworn guardian” or “trusted steward,” preserving the old spirit of informal but vital duty.

This evokes how old words resist simple synonym replacement, instead allowing broader semantic expansion grounded in original purpose. Language evolves, yet key origins endure. The Old English *„scip”*—ship—has given

Related Post

Kathryn Adams Limbaugh: A Journalistic Voice Bridging Tradition and Transformation in Media

SleepySoles GameBetaFlash Revolutionizes Sleep-Based Gaming with Peaceful Immersion

Figma for App UI Design: Mastering the Tool That Defines Modern Mobile Experiences

Unlocking the Enigma: Chellam Meaning Revealed in Bold Scientific Insight