Unlocking Life’s Blueprint: Where Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes Overlap in the Venn Diagram of Cellular Life

Unlocking Life’s Blueprint: Where Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes Overlap in the Venn Diagram of Cellular Life

Far beneath the surface of a world teeming with microscopic life lies a profound biological truth: all cells fall along a spectrum defined by complexity and evolution. The Prokaryote Eukaryote Venn Diagram serves not just as a graphic model, but as a window into the shared ancestry and divergent paths of cellular organization. This diagram reveals unexpected overlaps, challenging the rigid line we often draw between these two fundamental life forms.

By examining key shared features, structural contrasts, and evolutionary milestones, we uncover how cellular life has diversified while retaining core biological fundamentals—an intricate tapestry woven across billions of years of descent. At the heart of the Venn diagram lies the shared necessity for life-sustaining components: both prokaryotes and eukaryotes require DNA to encode genetic instructions, ribosomes to translate those codes into proteins, and membranes to compartmentalize cellular processes. “Despite their structural differences, at the molecular level, prokaryotes and eukaryotes rely on same chemical languages,” explains Dr.

Elena Varga, molecular biologist at the Institute for Evolutionary Genetics. Mitochondria, once independent organisms, now reside within eukaryotic cells as energy powerhouses, their bacterial origin embedded in mitochondrial DNA—a relic of endosymbiosis. So while eukaryotes evolved internal membrane systems, prokaryotes achieved functional complexity through circular chromosomes and mobile genetic elements.

Structurally, both domains feature genetic material enclosed within a plasma membrane, though the organization diverges sharply. Eukaryotic cells possess a defined nucleus surrounded by a nuclear envelope—a double-membrane barrier that spatially separates DNA from cytoplasmic functions. Prokaryotes lack this nucleus and DNA floats freely in the nucleoid region.

Yet, in a striking genomic convergence, some archaea—organisms once considered prokaryotic defaulters—display histone proteins that organize DNA similarly to eukaryotes, blurring the traditional boundaries.

The emergence of internal membrane systems in eukaryotes marks one of the most transformative evolutionary advances, enabling cellular compartmentalization and metabolic specialization.

Emerging from this complexity, eukaryotes exhibit membrane-bound organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and mitochondria—features absent in prokaryotes. Yet recent studies reveal prokaryotes are far more genetically flexible than once assumed. Horizontal gene transfer allows these organisms to acquire traits like antibiotic resistance and metabolic versatility, enabling rapid adaptation across extreme environments.“Some archaea and bacteria have evolved enough to mimic eukaryotic complexity through gene exchange, demonstrating that the prokaryote-eukaryote divide isn’t a wall, but a porous membrane,” notes Dr. Kenji Tanaka, evolutionary geneticist at Kyoto University. Filamentous and land-dwelling archaea, for instance, display internal structures once thought exclusive to eukaryotes, such as primitive cytoskeletal elements and vesicle trafficking systems.

This growing evidence challenges textbook dichotomies, suggesting the distinction between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is best viewed as a continuum rather than a binary split.Domain-specific hallmarks further illuminate this gradient: eukaryotic cells uniquely employ mitosis for division and complex RNA processing via spliceosomes, while prokaryotes utilize simpler, faster binary fission and often external RNA editing.

Yet extremes exist—some eukaryotes retain prokaryote-like ribosomes, and certain prokaryotes encode circular mtDNA resembling ancestral bacterial genomes.

Beyond structure and genetics, metabolic innovations distinguish domains. Eukaryotes dominate energy-rich environments through aerobic respiration and photosynthesis housed in organelles, while many prokaryotes thrive as extremophiles—oxidizing iron, fixing nitrogen, or surviving radiation—using specialized membranes and enzymes.

These adaptations, though functionally diverse, rest on shared metabolic pathways rooted in ancient universals. “Even in extremophiles, the core enzymes for ATP synthesis or transcription mirror those found in humans and yeast,” asserts Dr. Maria Lopez, microbiologist specializing in

Related Post

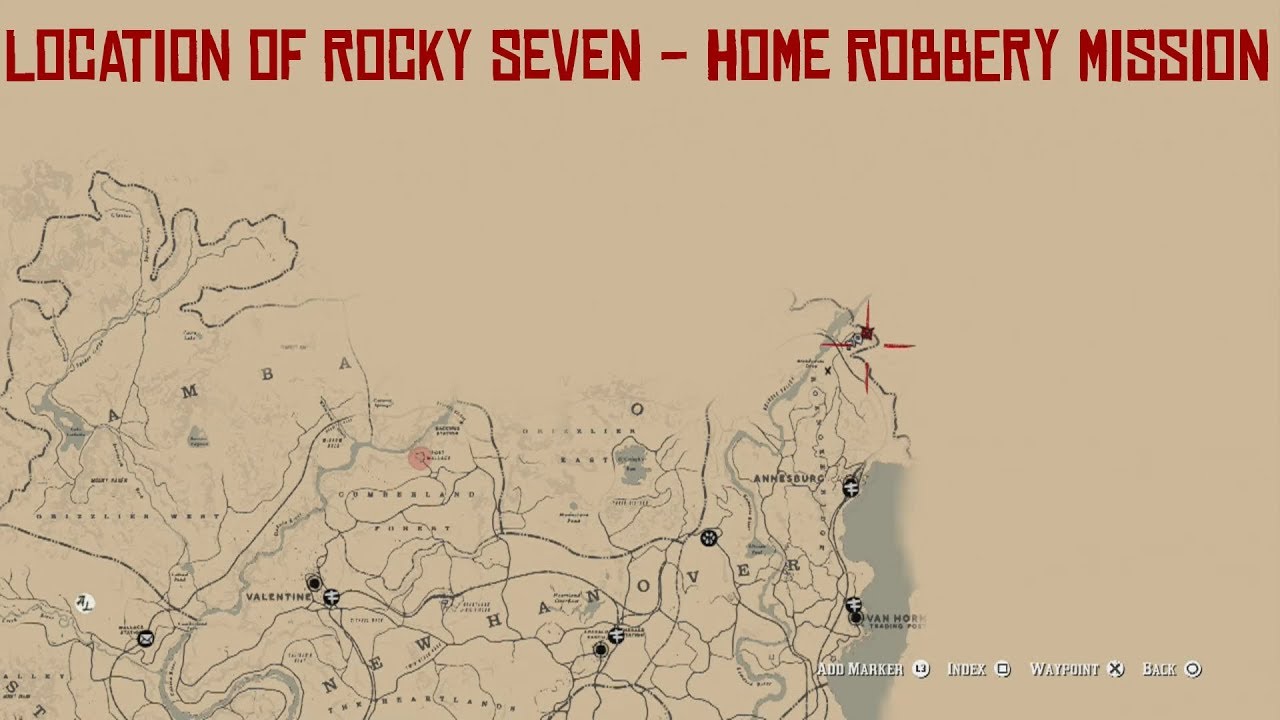

Discover the Hidden Humanities: Rocky Seven’s Quest Through Rockey Seven RDR2 Location

The Tension, Tragedy, and Legacy of Los Los Rehenes

Mitchell Robinson’s Wife: Unveiling the Quiet Strength Behind the NBA Star

Karen's Diner Indonesia: Redefining Rude Fun with The Ultimate Guide