What Is the Shape of the Water Molecule? Unlocking Nature’s Hidden Blueprint

What Is the Shape of the Water Molecule? Unlocking Nature’s Hidden Blueprint

At first glance, a water molecule may appear deceptively simple—two hydrogen atoms neatly paired with a central oxygen. Yet beneath this elementary structure lies a complex, asymmetric geometry that defines water’s remarkable physical and chemical properties. The quantitative shape of a water molecule—distinguished by its bent, or angular, form—lies at the core of water’s ability to dissolve countless substances, support life, and shape Earth’s climate and geology.

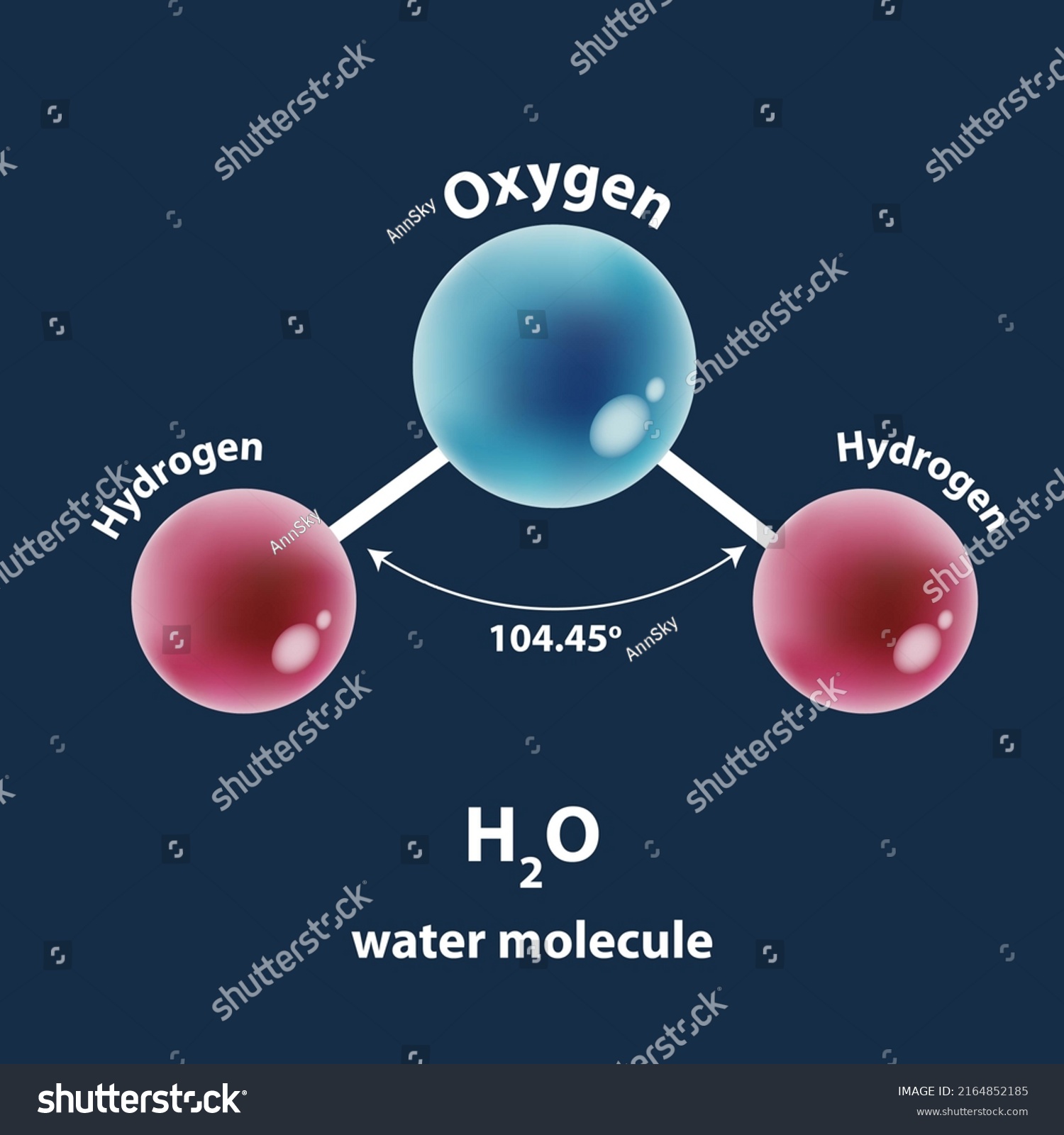

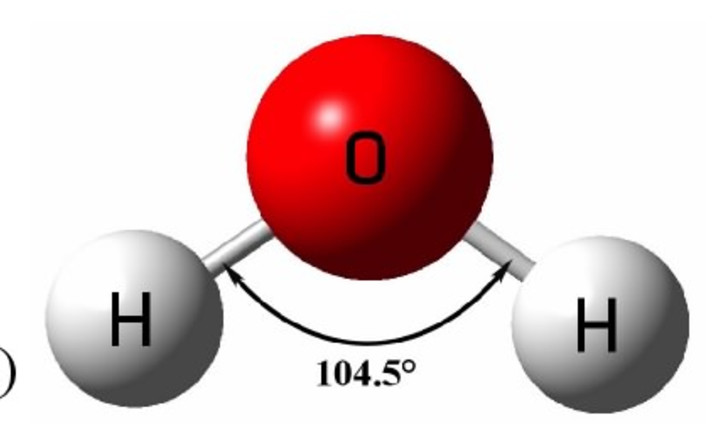

Understanding its molecular shape unlocks fascinating insights into why water behaves as it does, far beyond what casual observation reveals. The Shape of Water: A Bent, Angular Structure The water molecule (H₂O) consists of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to two hydrogen atoms. However, due to the way electrons distribute around the oxygen nucleus in quantum mechanical orbitals, the molecule does not adopt a straight line.

Instead, it adopts a **bent geometry** with a precise molecular angle. Measurements confirm the H–O–H bond angle measures approximately 104.5 degrees—a nearly tetrahedral arrangement distorted by electron pair repulsion, specifically stemming from two lone pairs on oxygen resisting full straight-line alignment. This bent configuration arises from **valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory**, a foundational model in molecular chemistry.

As explained by chemist Barbara McClintock in her seminal work on molecular geometry, lone pairs occupy more space than bonding pairs, pushing hydrogen atoms closer together and creating the characteristic angle. This subtle deviation from linearity profoundly influences how water molecules interact at the molecular level—enabling hydrogen bonding, cohesion, and solvent versatility. The Role of Polar Pinching in Molecular Polarity Water’s bent shape is not merely geometric—it directly generates the molecule’s polar nature.

Oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, pulling electron density toward itself and creating partial negative charges on oxygen, while hydrogen gains partial positive charges. The asymmetry of the bent form prevents cancellation of these dipoles, resulting in an overall molecular dipole moment. This polarity is critical: it allows water to form strong hydrogen bonds with itself and with other polar or charged substances.

The voltage between oxygen and hydrogen ends gives water a dynamic, polarized structure that turns it into nature’s most effective solvent. “Water’s bent geometry isn’t just a shape—it’s the key to its identity,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist at MIT.

“Without this 104.5-degree orientation, water’s polarity would diminish, compromising its role in biological systems and global water cycles.” The angle ensures that charges remain asymmetrically distributed, maximizing inter-molecular attraction. Experimental Validation of Molecular Geometry For decades, scientists have confirmed the bent shape of water through complementary experimental techniques. X-ray diffraction studies of ice and liquid water’s hydrogen-bonded networks show hydrogen atoms consistently angled around 105 degrees away from oxygen.

However, in liquid water—where molecules constantly tumble and reorient—the bent shape finds a dynamic equilibrium, maintained by fleeting but powerful hydrogen bonds. Spectroscopic methods such as infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy detect vibrational modes sensitive to molecular geometry. The O–H stretching vibrations resonate at specific frequencies only when hydrogen bonds preserve the bent orientation, offering direct evidence of the molecule’s angular structure.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) further reveals how lone pairs influence local electron clouds, reinforcing the VSEPR-based model. Historically, the 1931 X-ray crystallography work by Linus Pauling and Robert Corey laid the groundwork for predicting bond angles in molecules like water, though water’s hydrogen bonds required later refinement. Modern computational chemistry, using density functional theory (DFT), now simulates these interactions with atomic precision, consistently showing the 104.5° angle as the most energetically favorable configuration.

Implications: From Biology to Climate The molecule’s bent structure underpins water’s life-sustaining roles. Its polarity and hydrogen bonding confer high specific heat, enabling stable temperature regulation in living organisms and oceans. The angle allows water to form dipole-dipole and ion-dipole interactions critical for dissolving salts, nutrients, and proteins—processes fundamental to cellular function and geochemical cycles.

In climate science, the hydrogen-bonded network explains water’s high latent heat of vaporization, driving atmospheric heat transfer and weather patterns. The 104.5° geometry ensures efficient oxygen-electron sharing with solar radiation and atmospheric molecules, supporting deep convective currents. As climate physicist Richard Alley emphasizes, “Water’s molecular shape is silent yet profound—it’s why Earth’s weather systems work, and why life evolved here.” Why Shape Matters Beyond the Lab Beyond fundamental science, understanding the water molecule’s geometry informs technological innovation.

In water treatment, molecular modeling guides filtration methods that exploit hydrogen bonding for contaminant removal. In pharmaceuticals, the bent structure influences drug solubility and delivery—guiding the design of bioavailable compounds. Even in materials science, synthetic polymers mimic water’s polar interactions to develop hydrogels with targeted swelling or adhesion properties.

Everyday phenomena also trace back to molecular shape: why a drop rises in a plant’s xylem, why ice floats lighter than liquid water, or how water continuously coats surfaces in humidity. These obvious yet deep behaviors originate from the tiny, polar world of H₂O molecules bending at just the right angle to enable life’s most vital processes. In summary, the shape of the water molecule—bent, polar, and precisely angled at 104.5 degrees—represents far more than a chemical curiosity.

It is the silent architect of water’s ubiquity and utility: a polar, contact-seeking molecule whose geometry enables dissolving, regulating, and sustaining life on Earth. As advanced by modern chemistry, this bent configuration is not accidental—it is essential. And in understanding this shape, we grasp a key to nature’s most indispensable substance.

Related Post

Unlocking Precision in Design: The Essential Cover Proposal Pkm Kc Pdf in Modern Documentation

The Chosen Chaim Potok Pdf: A Profound Exploration of Identity, Intellect, and Faith

Uma Tier List: Decoding India’s Elite—Who Really Wields Power in Indian Sports?

Decoding CH<sub>3</sub>OH: The Lewis Structure Behind Ethanol’s Molecular Blueprint