Why the Robber Baron Defined the Gilded Age—A Ruthless Architect of Modern Capitalism

Why the Robber Baron Defined the Gilded Age—A Ruthless Architect of Modern Capitalism

In the shadowy haze of America’s Gilded Age, amid rising industrial titans who reshaped the nation’s economy and social fabric, the term “robber baron” emerged as both a separate accusation and a symbol of unchecked capitalism’s darker currents. These men—entrepreneurs whose fortunes were built on mining, railroads, steel, and finance—wielded economic power so immense it mirrored conquests of old, often acquired through aggressive monopolies, labor suppression, and political manipulation. Far from mere businessmen, they were mythologized visionaries whose ruthless methods laid the foundation for today’s global corporate landscape.

Understanding what a robber baron truly meant reveals not just a chapter of history, but echoes in the ethics of modern enterprise.

The origins of the “robber baron” label trace back to 19th-century public outrage over industrial oligopolies that crushed competition, exploited workers, and influenced government policy to protect their deals. Coined largely by reformers and critics, the term carried a loaded weight—evoking greed and criminality, though historians debate whether it oversimplified complex realities.

“These were men who saw the nation’s infrastructure not as a public good, but as an asset to dominate,” notes economic historian Lisa Anderson. “Their strength came not just from innovation, but from sheer force applied to markets and labor.”

Who Were the Most Iconic Robber Barons? Power, Vision, and Violence

Several figures stand out among the pantheon of robber barons, each emblematic of different arms of wealth accumulation.- John D. Rockefeller revolutionized oil with Standard Oil, crushing competitors through predatory pricing and secret rebates. By controlling 90% of U.S.

refining by the 1880s, Rockefeller not only innovated but engineered a monopolistic empire that spurred antitrust action—proving both his influence and the tensions his methods created. “Rockefeller’s genius lay in logistics and vertical integration,” explains Harvard’s Kris DeDeza, “but his methods—price wars, covert filtration—were indistinguishable from predation.” - Andrew Carnegie dominated steel through vertical integration, cutting costs and eliminating rivals. His philosophy, famously articulated in “The Gospel of Wealth,” argued that the rich had a duty to manage wealth for public benefit—though critics countered his philanthropy masked exploitation.

“Carnegie built industries that powered cities, yet built palaces while stripping workers of dignity,” historian David Nasaw observes. “His legacy reflects both transformative progress and deep moral fractures.” - Cornelius Vanderbilt built his fortune first in railroads, turning chaotic transport networks into efficient, profit-driven systems. Known for relentless negotiation and ruthless pricing, he consolidated lines into a national infrastructure that laid groundwork for modern logistics—while breaking competitors with unforgiving cost-cutting and aggressive takeovers.

Each man embodied a blend of visionary enterprise and unapologetic power, defining an era where capital accumulation often clashed with public interest.

Monopolies & Market Control: From Trusts to Trust-Busting

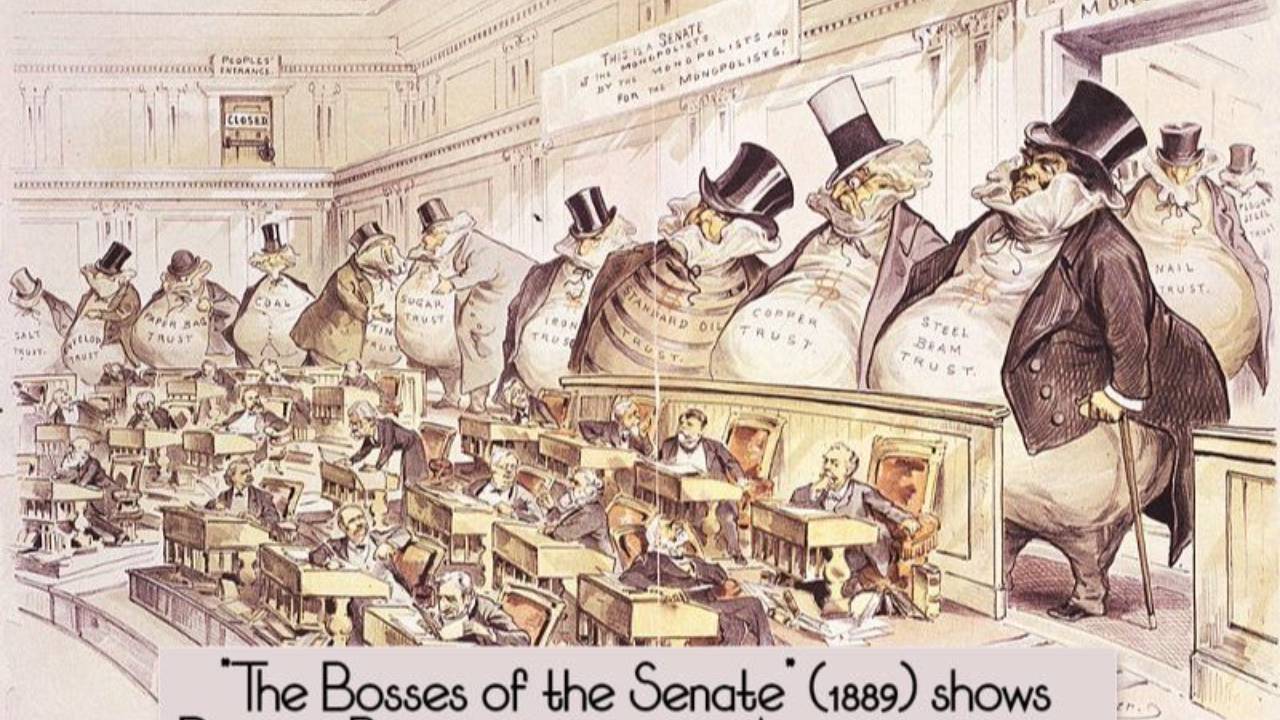

At the heart of robber baron activity was the formation of trusts—legal structures designed to centralize control over competitors under a single board. Such trusts enabled monopolies that stifled competition, manipulated prices, and imposed industrial mercenaries on labor forces.A pivotal example was Standard Oil’s dominance, which by the early 1900s controlled upwards of 90% of refining refinances—so effectively that Congress responded with the 1911 Supreme Court ruling breaking it apart. Seeing these trusts as threats to democracy, reformers pushed landmark antitrust legislation like the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), though enforcement was inconsistent for decades.

Robber barons exploited legal loopholes and political connections to expand influence beyond business.

Many sat in Congress, lobbied state legislatures, and funded political machines. Vanderbilt’s family, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil executives, and Carnegie’s network built relationships that shaped policy, tariffs, labor laws, and infrastructure investments. “These men didn’t just run companies—they ran systems,” notes legal scholar aunque L.

Carter. “Their power seeped into governance, blurring lines between private gain and public service.” This fusion of commerce and political influence remains a central concern in modern debates over corporate lobbying and regulatory capture.

Labor, Exploitation, and the Human Cost

The rapid industrial expansion championed by robber barons came at a steep human toll, particularly for working-class Americans.Fueled by demand and ruthless efficiency, factory owners embraced wage suppression, all but eliminating job security and promoting dangerous, unsafe working conditions. The Homestead Strike (1892) and the Pullman Strike (1894) exemplified violent labor conflicts sparked by these tensions—moments when industrial ambition clashed furiously with worker rights.

Robber barons dismissed labor struggles as inevitable’sides of progress, viewing union demands as inhibitors to growth.

“Management saw employees as linchpins of productivity, not people,” states historian Daniel Tichenor. “Arbitration and fair treatment were luxuries, not strategies.” Child labor, 12- to 16-hour shifts, and casual firing practices were widespread, justified privately by the need for lean, flexible operations. The moral dilemma persists today: Can massive economic growth coexist with humane labor standards, or does one inevitably exploit the other?

Legacy: How Robber Barons Forged the Modern Corporate World

The influence of robber barons extends far beyond their lifetimes. The industrial structures they created—the vertically integrated steel, oil, and railroad empires—became blueprints for today’s multinational corporations. Their emphasis on scale, vertical integration, and market dominance inspired pragmatic philosophies like shareholder value that dominate modern business today.Yet so too does their legacy a cautionary tale—of unchecked power, labor inequality, and regulatory erosion.

The very systems these men built now anchor global supply chains and financial markets, yet their methods inform contemporary debates on corporate responsibility, dynastic wealth, and antitrust enforcement. While some view them as impossibly efficient titans who accelerated American prosperity, others remember them as architects of a system that prioritized profit over people.

“They weren’t villains we can punish,” acknowledges economic historian Megan Folward, “but architects of a new economic order—one that we still struggle to remake.” In understanding what a robber baron truly meant, we confront both the astonishing promise and the enduring peril of industrial capitalism—a duality as relevant now as in the Gilded Age.

Related Post

What Does Excluding Mean? The Power and Pitfalls of Omission in Information

Gavin Harris: The Rising Football Star Redefining Modern Attacking Talent

Sam Reid’s Wife: A Quiet Glimpse Into an Actor’s Private Life

Master Windows 10 Pro VM: Step-by-Step Setup & Optimization Guide for Maximum Performance