Zamindars vs. Tax Farmers: The High-Stakes Battle for Revenue and Power in Colonial India

Zamindars vs. Tax Farmers: The High-Stakes Battle for Revenue and Power in Colonial India

In the intricate tapestry of India’s pre-colonial and colonial fiscal history, the systemic rivalry between zamindars—the hereditary land rulers—and tax farmers—profitable but often reviled revenue contractors—defines a pivotal struggle over land, power, and taxation. This conflict shaped agricultural economies, social hierarchies, and governance patterns across Mughal and British India, reflecting deeper tensions between institutional land authority and rent-seeking commercial exploitation. Rooted in divergent incentives and methods, the clash between zamindars and tax farmers underscores how taxation became not just an economic tool but a battleground for control.

The Zamindari System: Legacy of Mughal Administration, Identity as Local Sovereigns

The zamindar class emerged during the Mughal era as semi-autonomous landholders granted hereditary rights to collect revenue in exchange for military and fiscal duties. Unlike mere tax collectors, zamindars often functioned as local sovereigns: managing agriculture, resolving disputes, and maintaining order within their dominions. Their authority was deeply institutionalized, placing them at the heart of rural society.Zamindars derived legitimacy from long-standing traditions and familial control over vast tracts of land. They were not transient revenue extractors but stewards whose status depended on agricultural productivity and social stability. As historian Radha Kishan notes, “Zamindari was more than a system of land revenue—it was an enduring socio-political institution.” Their role secured a steady flow of income through regular land taxes, typically paid in cash or kind, tied to crop cycles and land fertility.

This embedded power gave zamindars considerable influence: they could mobilize labor, arbitrate local conflicts, and shape rural life according to their interests. Yet their status made them targets during transitions—particularly under British rule, when colonial reforms redefined their rights and responsibilities amid transformations in fiscal policy.

Tax Farmers: The Profit-Driven Contractors of Colonial Finance

Tax farmers represented a starkly different model—private agents contracted by colonial administrations to collect revenue in advance, bearing the full financial risk of shortfall.Unlike zamindars, their interest lay not in long-term land stewardship but in maximizing revenue within tight time frames, often using aggressive collection tactics. Their business relied on speed, efficiency, and coercive enforcement, leading to widespread resentment among peasant communities. “The tax farmer’s role was transactional, mercenary, and short-term obsessed,” observes historian Jean Dreze.

“While zamindars sought stability and influence, tax farmers thrived on extracting immediate surplus—often at the cost of agricultural sustainability and peasant survival.” Their profits depended on over-assessment rather than sustainable yield, incentivizing rigid, exploitative collection methods. Under British rule, the system expanded through grants of zamindari rights with additional tax-collection privileges, effectively empowering a class of contractors whose authority stemmed from coin, not community ties. This shift destabilized rural economies, as tax farmers prioritized immediate revenue yields over long-term agricultural health, precipitating cycles of distress and default.

Systemic Tensions: Control, Accountability, and Rural Distress

The fundamental contrast between zamindars and tax farmers centered on accountability and investment in agricultural prosperity. Zamindars, embedded in local power structures, bore collective responsibility for revenue stability and rural order. Their income depended on consistent yields, aligning their interests, at least superficially, with land productivity and peasant welfare.Yet colonial pressures often pushed them toward aggressive collection, blurring the line between legitimate tax farming and extraction. In contrast, tax farmers operated without constitutional oversight, shielded from local accountability. Their fees—increased fees, penalties, and debt traps—exacerbated peasant hardship.

Historian Partha Chatterjee highlights, “Tax farming transformed taxation from a social contract into a predatory enterprise, where profit superseded justice.” This created a vicious cycle: over-assessment led to land abandonment, declining yields, rising unrest, and eventually, fiscal shortfalls that forced the state to adjust—but rarely in favor of farmers. Yet, paradoxically, tax farming injected liquidity into colonial coffers by front-loading revenue. The system rewarded speed and severity, producing short-term gains but long-term instability.

Zamindars, despite their hierarchical dominance, sometimes acted as mitigating forces, using influence to moderate excesses—though often failing to halt systemic exploitation.

The Colonial Reckoning: Reforms, Resistance, and the Erosion of Ancient Orders

The clash between these two groups intensified under British colonial rule, as administrative reforms sought to codify revenue collection through systems like the Permanent Settlement (1793) in Bengal. This landmark policy enshrined zamindars as official revenue owners—solidifying their legal status while binding them to fixed tax quotas.Though intended to stabilize revenue, it compressed incentives: zamindars demanded high rents to meet state demands, accelerating peasant exploitation and indebtedness. Tax farmers, though less formally integrated post-1793, persisted through indirect control and contractual levers, their role morphing into that of quasi-state actors through economic dominance rather than formal office. Yet resistance simmered: agrarian uprisings, local litigation, and peasant petitions repeatedly challenged unbalanced power.

In numerous districts, zamindars and tax farmers became symbols of state-imposed exploitation, catalyzing calls for fiscal justice. The rivalry thus mirrored broader colonial contradictions—between order and oppression, tradition and extraction, efficiency and equity. Each group, in its own way, shaped India’s agrarian evolution, leaving legacies that influenced post-independence land reforms and taxation policies.

Enduring Lessons: Power, Perspective, and the Politics of Revenue

The historical contest between zamindars and tax farmers reveals taxation not as a neutral administrative function, but as a deeply political battleground where competing visions of authority and equity clashed. Zamindars, as institutions rooted in land and community, represented continuity and localized control; tax farmers, as profit-seeking intermediaries, epitomized extractive rent-seeking. Their conflict underscored how institutional legitimacy, accountability, and incentive structures determine the success—or failure—of revenue systems.Today, this history informs understanding of rural inequality, state-building, and the role of private intermediaries in public finance. The unresolved tensions between extractive practices and sustainable stewardship persist in modern debates over land rights and taxation. By examining the zamindar-tax farmer struggle, one gains critical insight into how systems of control shape economies and societies—reminding us that revenue is never just money, but the very pulse of governance.

Related Post

Shock Absorber Safety: The Data Sheet Guide Every Driver Must Know

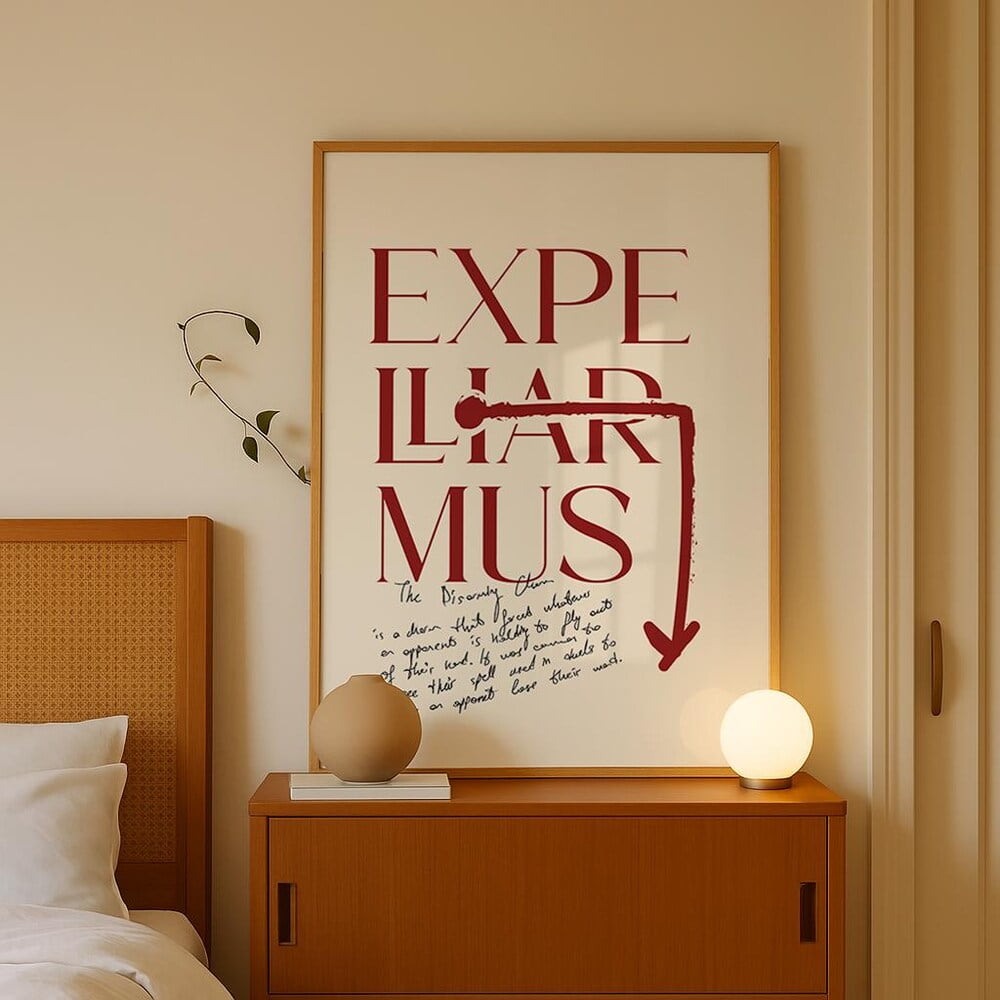

Expelliarmus Mastery: Disarming Spell Wand Movement That Turns Foes Into Allies

Natalie Spala Drives Innovation in Women’s Health Through Groundbreaking Research and Advocacy

Navigate Justice Directly: A Simple, Trusted Guide to the Massachusetts Court Case Lookup System